A comic book just grounded planes and decimated tourism in Japan – for real

It sounds like the plot of a comic itself. A manga artist has a dream, draws it, and decades later, the world responds not with admiration, but with cancelled holidays, empty flights, and spiralling tourism numbers.

But that’s exactly what happened this weekend in Japan.

On Saturday 5 July 2025, a day that was predicted in a comic story to bring catastrophic destruction, the country braced for a disaster that – fortunately – never arrived. But that didn’t stop thousands from changing their travel plans, airlines from cancelling flights, and social media from feeding a full-blown, anxiety-laced frenzy.

All because of a single comic book. So what on earth happened?

(To publish your own manga, see our tips.)

The manga that "saw the future"

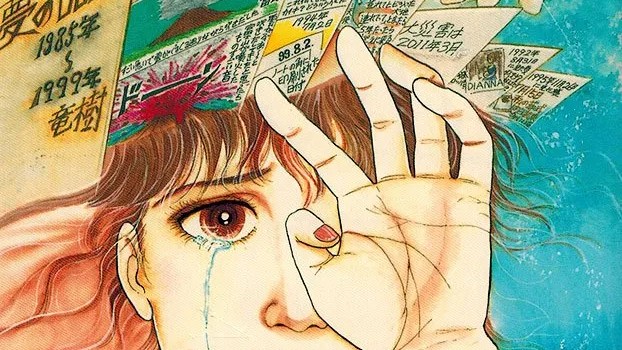

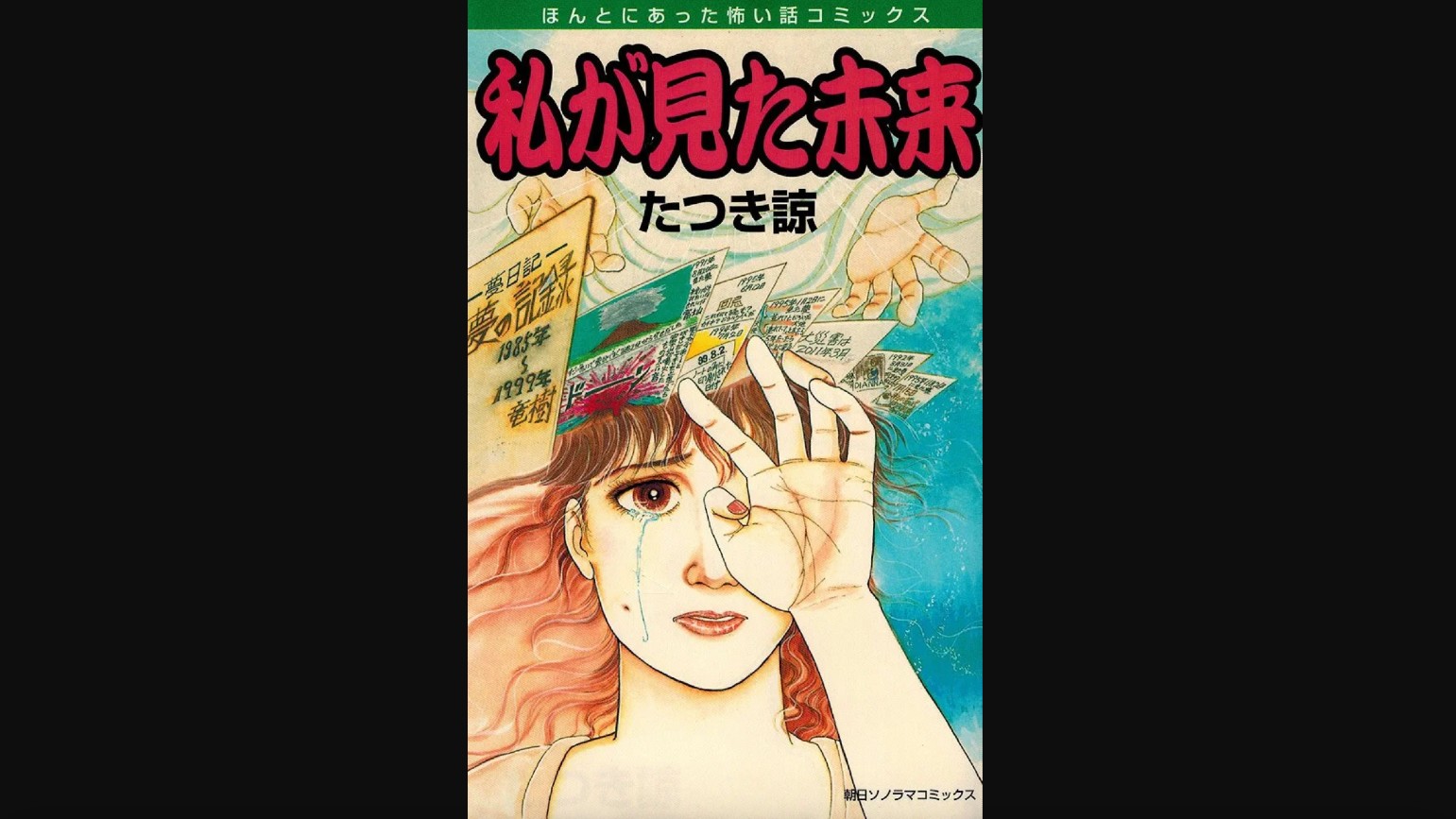

The source of the panic was The Future I Saw, a Japanese comic by Ryo Tatsuki, first published in 1999 and republished in 2021 by Asuka Shinsha. It was a compilation of what Tatsuki describes as “precognitive dreams”, one of which is claimed to have eerily predicted the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami: the devastating real-life disaster that killed nearly 20,000 people.

The apparent accuracy of that prediction, printed in the original edition over a decade before the event, gave the manga a kind of retroactive authority. So when the 2021 edition included a warning about a disaster in July 2025, some readers didn’t take it lightly.

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

When some interpreted the warning even more precisely – pinpointing 5 July as the day – it spread like wildfire across social media platforms, particularly in Hong Kong.

In the weeks leading up to 5 July, fear began to override logic. Hong Kong, a market with traditionally strong tourist links to Japan, saw arrivals to the country fall 11% year-on-year in May—despite Japan’s overall tourism still booming. For some travel agencies, Japan-bound bookings halved.

Greater Bay Airlines suspended flights to Tokushima from September due to low demand. Other carriers followed suit. Travel insurance products suddenly included earthquake cover. Bookstores capitalised on the panic, placing warning banners beside stacks of The Future I Saw. One in Tokyo read, “Whether you believe it or not is up to you.”

It’s worth noting that Japan saw over 900 small tremors in the first days of July, mostly around the Tokara Islands. While that's not unusual for a country sitting on the Pacific Ring of Fire, the timing ramped up the panic further.

Art or augury?

Tatsuki herself was quick to clarify things. Speaking through her publisher, she stated in a rare interview: “I am not a prophet.” The promotional text about July 2025, she added, was written by an editor, not by her. While she acknowledged the anxiety, she urged readers to focus on preparedness rather than prophecy.

Still, the numbers speak volumes. Over a million copies of The Future I Saw have been sold. Her new release, Angel’s Last Words, launched in June, quickly climbed Amazon Japan’s bestseller charts. Whether Tatsuki intended it or not, her work has clearly struck a nerve. And now, it’s struck the economy too.

For creative professionals, this surreal episode raises serious questions. Can a piece of art, intended as a personal, possibly even whimsical reflection, carry unintended social consequences? Should artists be held accountable for how their work is interpreted once it leaves their hands?

The answer, as always, is complicated.

Art is open to interpretation. It stirs emotions, prompts reflection, and occasionally causes hysteria. Creators hope their work will resonate, but rarely imagine it grounding planes or knocking an entire tourism sector off course.

And yet, this story proves that art – especially when coupled with timing, context, and amplification through social media – can wield astonishing influence.

Whether we like it or not, audiences don’t always separate fiction from fact, metaphor from message. Creatives navigating public platforms in 2025 may need to consider not just what they say, but what people think they’re saying.

Postscript: the day after

Ultimately, the predicted disaster has not come to pass. Japan remains firmly above sea level. No asteroid has appeared in the sky. No mega-tsunami has risen from the depths.

But the story will linger. It’s already become a case study in media literacy, mass psychology, and the virality of fear. And it also stands a reminder of the often under-acknowledged power artists hold—not as prophets, but as mirrors to the collective imagination.

In an age of algorithms and online echo chambers, of fake news and public distrust in mainstream media, even the most niche creative work can leap into global consciousness overnight. And that's both exhilarating and sobering.

Because sometimes, even a manga can move markets.

Tom May is an award-winning journalist specialising in art, design, photography and technology. His latest book, The 50 Greatest Designers (Arcturus Publishing), was published this June. He's also author of Great TED Talks: Creativity (Pavilion Books). Tom was previously editor of Professional Photography magazine, associate editor at Creative Bloq, and deputy editor at net magazine.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.