How Life of Pi’s tiger was created

Oscar-winning VFX supervisor Bill Westenhofer discusses the manpower and technical advances that enabled Rhythm & Hues to create Life of Pi’s all-too-believable co-star.

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Five times a week

CreativeBloq

Your daily dose of creative inspiration: unmissable art, design and tech news, reviews, expert commentary and buying advice.

Once a week

By Design

The design newsletter from Creative Bloq, bringing you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of graphic design, branding, typography and more.

Once a week

State of the Art

Our digital art newsletter is your go-to source for the latest news, trends, and inspiration from the worlds of art, illustration, 3D modelling, game design, animation, and beyond.

Seasonal (around events)

Brand Impact Awards

Make an impression. Sign up to learn more about this prestigious award scheme, which celebrates the best of branding.

Any lingering doubts that we’ve yet to tackle the animal analogue of the Uncanny Valley were buried at sea when millions of moviegoers came face to face with Richard Parker, the Bengal tiger in Life of Pi. After watching the lengthy and pivotal performance from a shipwrecked tiger, the public were left wondering how the film-makers had coaxed a real animal into doing all those things. The animation was so good that the Indian film board refused to show the film at first, as they thought the emaciated tiger was real. Rhythm & Hues had to send them reference shots to prove the animal was a digital creation.

Rhythm & Hues VFX supervisor Bill Westenhofer says director Ang Lee first approached the studio with a question: would a digital creature look more or less convincing in stereo 3D? “We worked on some tests for him, which showed that the 3D definitely helped to make it feel more real, but also showed that more detail and care was required for it to really stand up.”

Westenhofer says experience gained and tools built since its work on 2001 release Cats & Dogs were invaluable, with Richard Parker the spiritual offspring of the lion Aslan in The Lion, The Witch & The Wardrobe. Nonetheless, it took around a year to make the film’s 158 CG tiger shots, with a team of 40 animators and 120 other artists working in the US and India.

“It was definitely a more complex creature than we’d ever dealt with before,” says Westenhofer. “A great example was the paws – we had as many controls in there as we had with the entire facial rig in Aslan. In the past we spent so much time focusing on the face, but once we began looking at our reference we realised just how complex a creature’s paws are. You can see the claw retracting and the sheath around it working in some shots.”

The team has access to a quartet of tigers owned by renowned trainer Thierry Le Portier. “Even though the real tigers were used in 20 shots, Thierry’s involvement meant we had unprecedented access to the creatures. Whenever we had a shot to work on, we always had some reference in the right ballpark.”

This was especially valuable for working out how a tiger would react to the story’s extreme situations. “It’s very hard for an animator not to subconsciously anthropomorphise things,” says Westenhofer. “You know what the scene needs to portray so can’t help but relate it to your own human reactions. Thierry explained that, rather than looking agitated, a very nervous tiger will try to act as nonchalant as possible, for example.”

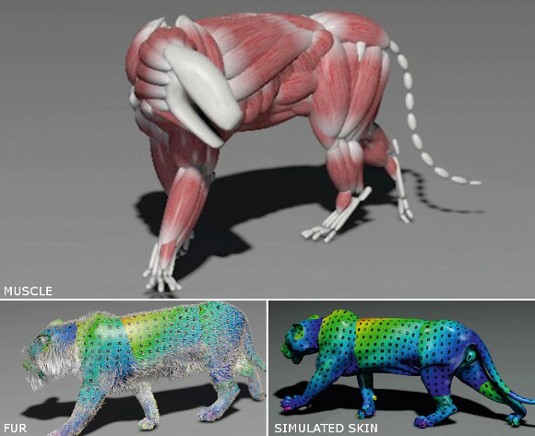

The studio ultimately built four adult versions of the creature, plus an additional adolescent one (with smaller proportions but proportionally larger head and paws) for the earlier scenes. Muscle simulation was crucial to creating an authentically toned body, with two skin layers then draped over the top. On the face, however, Westenhofer says they took a more procedural approach, creating a huge volume of blend shapes that could allow animators to match the expressions of the real tigers. “The muscles are relatively small in the face, so you can end up fighting with it if you try too hard to have the muscle drive the expressions. Again Thierry was a great help – we’d run the facial performance past him to make sure we were showing motions and emotions correctly.”

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

Rhythm & Hues’ entire creature pipeline is built around proprietary tools, with Voodoo used for Parker’s animation, Wren for rendering, and Icy for final compositing. The fur tool is one that has continually evolved over the last decade. “We created geometry to give the animators a sense of the size of the coat, but generally they worked without the fur, and then that would go to the tech animators to have the hair and dynamics added. With this creature there weren’t too many surprises after the fact. Any further adjustments required were usually down to the stereoscopy.”

Westenhofer says the biggest headaches arose when the tiger and its dynamic fur were required to interact with water that had been simulated in Houdini. “We would animate the tiger in the lifeboat against the water simulation so he looked like he was in danger of drowning, for example. But then you’d have to re-run the sim and the tiger animation would change the fluid dynamics, so you’d have to go back in and tweak the animation and then run the sim again. It was a big, cyclical loop with one element impacting back onto the other.”

Discover the best 3D movies of 2013

The Creative Bloq team is made up of a group of art and design enthusiasts, and has changed and evolved since Creative Bloq began back in 2012. The current website team consists of eight full-time members of staff: Editor Georgia Coggan, Deputy Editor Rosie Hilder, Ecommerce Editor Beren Neale, Senior News Editor Daniel Piper, Editor, Digital Art and 3D Ian Dean, Tech Reviews Editor Erlingur Einarsson, Ecommerce Writer Beth Nicholls and Staff Writer Natalie Fear, as well as a roster of freelancers from around the world. The ImagineFX magazine team also pitch in, ensuring that content from leading digital art publication ImagineFX is represented on Creative Bloq.