The best 1980s animated films include one of my all-time favourites

From Akira to The Little Mermaid, here's how the 1980s changed animation forever.

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Five times a week

CreativeBloq

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Once a week

By Design

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Once a week

State of the Art

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Seasonal (around events)

Brand Impact Awards

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

1980s animated movies can be seen as a moment in time when everything began to change, whether its new technology, artistic direction and audiences embracing world animation, something shifted.

I've already cover some of the groundbreaking animated movies of the 1970s, the best cartoons of the 1960s and animated films of the 1950s, but by the 1980s, animated movies continued to enjoy global production and release. The sizable presence of the Disney animated feature remained and the studio began to stabilise after adjusting to the impact of Walt Disney’s death in 1966 on the direction of the company.

Critically, anime asserted its international screen presence, enjoying increasing recognition across Europe and America and director Hayao Miyazaki began to emerge as an anime director of note at Studio Ghibli. In British cinema, several notably sombre animated features were produced that artfully told stories of great seriousness. In doing so, they reminded audiences that animation does not have to be synonymous with the playful and light-hearted.

Late in the decade, the Disney Animation Studio saw its popular and critical fortunes take a quantum leap with the release of Basil The Great Mouse Detective, Oliver & Company and then watershed release of The Little Mermaid. In serious contrast, Czech surrealist Jan Svankmajer was at work, as were the Brothers Quay in the UK with their mesmerising experimental and abstract animation.

Below I list some of my favourite animated films of the 1980s, and meet creators working today who are influenced by them. Inspired? Then read our guide to the best animation software and begin telling your own stories. You may want to catch up on the 12 principles of Disney Animation too.

Best animated films of the 1980s

01. The Secret of NIMH

Bluth had been an animator at the Walt Disney Animation Studios and had left in the late 1970s, frustrated with the company’s attitude to animation at that time.

(United Artists, 1982)

Former Disney animator Don Bluth announced his ambition for cel animation with his directorial debut, an adaptation of the novel Mrs Frisby and the Rats of NIMH. The film is a key animated feature of the decade, notable for the fluidity and personality of character movement.

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

The film also showcases a sophistication of lighting and other effects. Speaking about NIMH during the summer of 1982, Dors Lanpher, effects animator on the film, explained that, “What we’ve attempted to do is give the picture a lot of depth by using heavy colour and a lot of animated shadows.” At the time of the release of The Secret of NIMH Bluth said that “Animation is a beautiful art form that is in danger of dying out.’”

02. The Snowman

The Snowman was nominated for Best Animated Short Film at the Oscars in 1983 and won a BAFTA for Best Children’s programme in 1983.

(TVC London / Channel 4, 1982)

A seasonal tv classic that’s central to Christmas tv programming in the UK, The Snowman is an adaptation of Raymond Briggs’s story of the same name. Lyrical and sentimental, the film captures the silence of a snowy winter.

For Shaun Magher, animator and Course Director BA (Hons) Digital Animation and MA Feature Film Development at Birmingham City University, he notes that “In my opinion, The Snowman broke new ground in the area of rendering.

The use of shading on frosted cel helped establish an authentic depiction close to the original illustrations from the book. For me, apart from Diane Jackson’s wonderful vision to bring this story to life and her commitment to the story, and in particular the visual storytelling.

This film has no dialogue and particularly impressive were the wonderful bird’s eye-view sequences by Steve Weston. The sense of movement across the landscapes was exceptional and was the first time I had ever seen this. It was really inspiring for a young animator.

I also remember the rendering teams having fun sketching in the shadow of a helicopter, which was very subliminal. Diane’s integrity to the story will always make this film a seasonal classic. I was very lucky to have been mentored by Dianne when I studied Animation at the NFTS. Her advice and guidance resonated with me, and it always will.”

03. Twice Upon A Time

Henry Selick, David Fincher and Harley Jessup all worked on this film and would go on to become major American fantasy filmmakers in animation and live action. George Lucas was executive producer of the film.

(Warner Bros., 1983)

This movie, directed by John Korty, is a true cult classic: a fantasy piece about two factory workers who foil the plans of a tyrannical oaf named Synonamess Botch.

The story, as its title indicates, take a fairy tale kind of approach to its plot and characterisations and is visually distinctive on account of its use of a technique that the production dubbed ‘lumage’ whereby cutout character designs were lit from below on a light table.

In an era of photorealistic animation, it’s worth invoking the refreshing example of Twice Upon A Time, a cult classic that was only finally released on DVD in 2015.

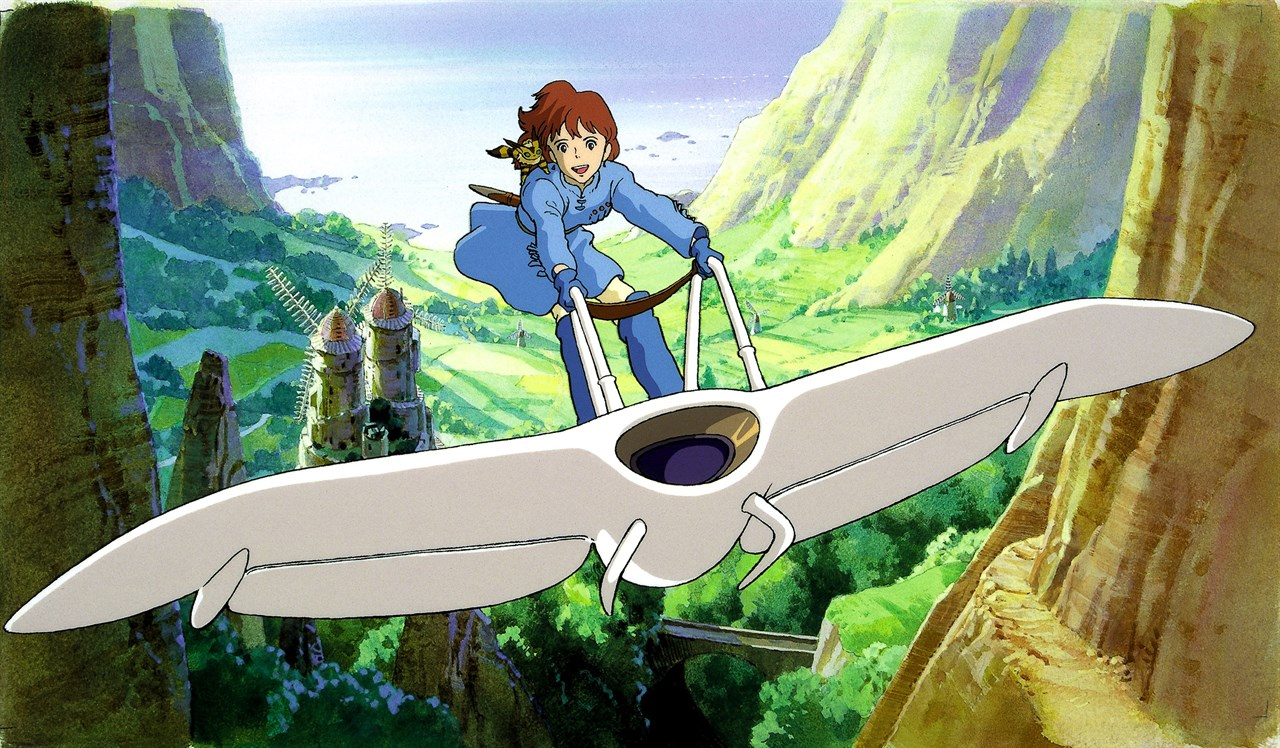

04. Nausicca of the Valley of the Wind

Nausiccaa has her inspiration not in Japanese culture but in the Latin poem, Metamorphoses. Of Nausicaa, Miyazaki commented in an interview with Young Magazine in 1984 that “Nausicaa is not a protagonist who defeats an opponent, but a protagonist who understands, or accepts.”

(Studio Ghibli, 1984)

An adaptation of the manga, Nausicaa marked the feature film directing debut of Hayao Miyazaki. The film is a science fiction post-apocalyptic story and the film delights in placing its young protagonist in immense natural and wilderness environments that are often mysterious and threatening and often wondrous.

In his book A Hundred Years of Japanese Film, Donald Richie explains that: “In Japanese film, the compositional imperative is so assumed that it is the rare director who fails to achieve it.” This attention to the arrangement of characters, space and colour is a distinction of this movie and all of Miyazaki’s subsequent projects.

05. When the Wind Blows

When the Wind Blows was originally a graphic novel written and illustrated by Raymond Briggs.

(Film Four International, 1986)

When the Wind Blows is the most sombre of films; depicting the attempts of an elderly couple, Jim and Hilda, to survive the detonation of a nuclear bomb.

For James Farrington, Rough Layout Artist at DNEG Animation, he recalls working on the film at the start of his career: “I was mainly doing clean up and lots of in-between drawings from various animators and felt really lucky to have my first film job on something that I felt was such an important film.

"The characters (in When the Wind Blows) of Jim and Hilda are portrayed as being naïve to the point of stupidity, trusting that the world will soon return to normal, and the ‘government’ will step in and take control again after the nuclear holocaust of World War Three.

"Throughout the film they continue to slowly die from radiation sickness and the rendition of them gradually losing their hair, with cheeks becoming sunken and getting thinner and sicker become so traumatic for one artist on the crew that she actually had to quit the production.”

Gary Kelly, Compositing Supervisor at DNEG Animation notes that, “When The Wind Blows has haunted me my whole life. Set in a working-class home, the story’s emotional weight comes from its ordinariness. The familiarity of the place and characters made the horror of their situation so much more affecting".

He adds: "The film’s visual style, a blend of traditional 2D animation with stop-motion sets, for me, perfectly compliments the simple, mundane world the characters inhabit; whilst serving equally as a contrast to the horror of what is unfolding. Raymond Briggs stories, particularly this film, made me a more curious person. The film’s mixed discipline approach started my interest and eventual career in animation and VFX."

06. An American Tail

In his recently published autobiography, Somewhere out There, Don Bluth recalled of his work on An American Tail that “I was always thinking about how to make this mouse story different from NIMH and The Rescuers. Along with Steven (Spielberg) we went for the nostalgic look of Walt’s movies from the 1930s and 1940, which had a rounded, cuddly feel.”

(Universal Pictures, 1986)

It was film music composer Jerry Goldsmith, during work on Poltergeist (1982), who urged its producer Steven Spielberg to watch Bluth’s great labour of love, The Secret of NIMH.

That led to Spielberg offering Bluth a story idea for the film that became An American Tail. The film was hugely popular and led to a second collaboration with Steven Spielberg (and George Lucas, too): The Land Before Time (1988).

07. Alice

Svankmajer did not consider hiomself an animator but a filmmaker. He once said that “Objects conceal within themselves the events they’ve witnessed. I don’t actually animate objects. I coerce their inner life out of them…”

Film Four International / Condor Films, 1988)

Based in Prague, Jan Svankmajer was a surrealist filmmaker for whom surrealism was not an aesthetic but a psychology.

He was a poet, ceramacist and sculptor and regarded animation as a way to explore the human psyche with a form and tone of animation that could be shocking and even horrific.

Most of Svankmajer’s career engaged with animated shorts. Alice was his first animated feature; an adaptation of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.

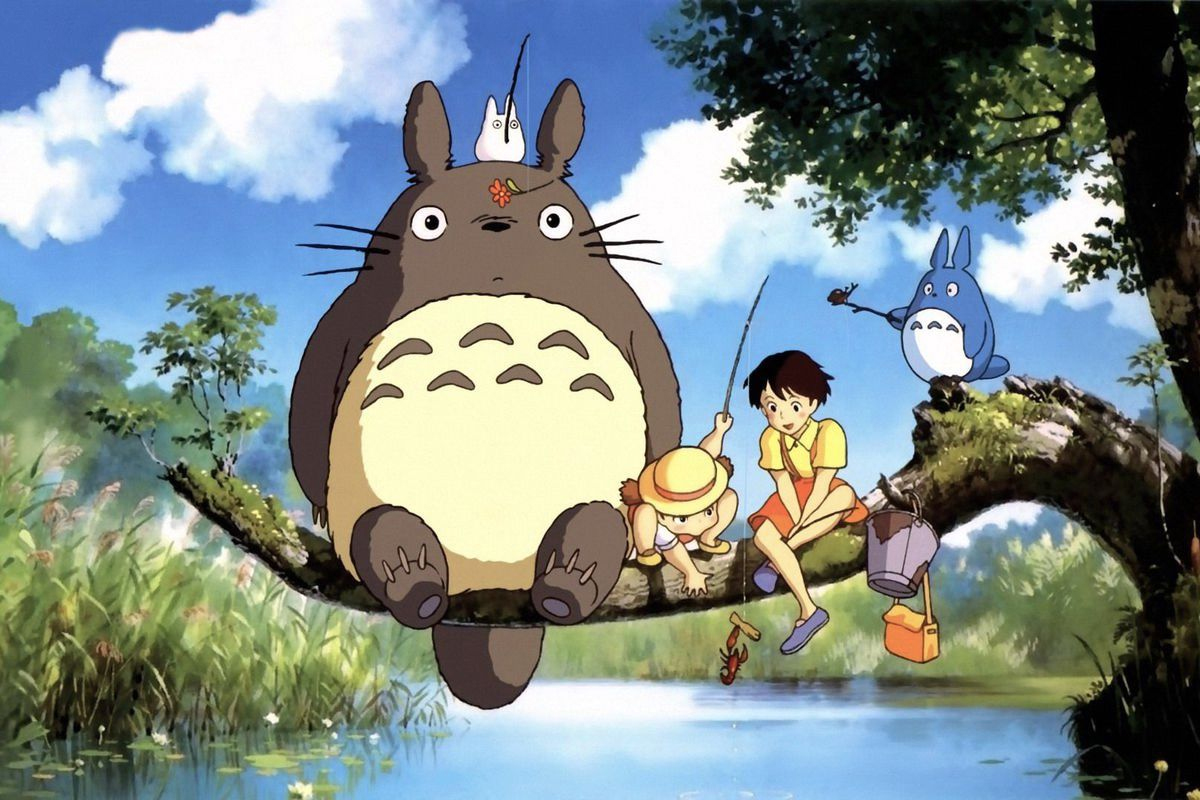

08. My Neighbour Totoro

My Neighbour Totoro was in production alongside Grave of the Fireflies and was directed by Hayao Miyazaki. Legendary Japanese director Akira Kurosawa cited My Neighbour Totoro as a favourite film of his. Totoro became the Studio Ghibli mascot.

(Studio Ghibli, 1988)

One of the most beloved Studio Ghibli movies, My Neighbour Totoro is a delightful fantasy film about the friendship between two children and the otherworldly creature named Totoro.

For Kayn Garcia, Animation Supervisor at Framestore: “My Neighbour Totoro and Hayao Miyazaki films in general have a beautiful sense of simplicity and clarity in his characters' performances. There is a powerful sense of depth and emotion that comes from the smallest change of details in a performance. Less is always more.”

09. Akira

Akira adapts a popular manga series by Katsuhiro Otomo that ran in Young Magazine in December 1982. The manga was not originally created with the possibility of a film in mind.

Upon release, Akira became an instant classic. It explicitly explores the impact for the good and the bad of technology in its story of a teenage boy subjected to experiments by the military which unleash destructive psychic powers.

Gavin Strange, Director and Designer at Aardman, discusses the importance of Akira to him:

“It’s a running joke with my creative friends that if a week goes by and I don’t mention Akira, then something is gravely wrong. The 1988 anime masterpiece by Katsuhio Otomo is a part of my creative DNA now, it’s part of my origin story really.

"My world of animation was Aardman and Disney – fun, charming, beautiful, quirky animation for all the family. But seeing Akira was something else. Suddenly I discovered animation can be challenging, surreal, dark, dystopian and more.

"Teenage outlaw biker gangs in a post WW3 Japan entangled with a telekinetic god-like force that threatens to destroy the fabric of reality itself!? I AM IN! That was why it’s stuck with me all these years, it was so eye-opening – literally – the art of animation on display is in a world of its own too.

"Watching it now, as I often do, I’m still struck with how beautiful it is. It was an incredibly complex undertaking in 1988, and was so unique in so many ways. Lip-sync dialogue and 24 frames per second was unheard of for anime at the time but the gamble pays off, it looks just as fantastic today in 2025.

"It’s a true masterpiece, and the fact that after many repeat viewings, I still don’t quite understand it all, means it has this magical quality, a mythical beast that cannot be tamed. What a creation. Akira, forever."

10. Grave of the Fireflies

Isao Takahata had been nine years old when the US dropped bombs on the city of Kobe, on June 29th 1945.

(Studio Ghibli, 1988)

Directed by Isao Takahata, Grave of the Fireflies was key in carrying the name and output of Studio Ghibli to international audiences. The film does not shy away from illustrating the physical trauma and horror of war.

In his book for the BFI Classics series about Grave of the Fireflies, Alex Dudok de Wit that at the time of the film’s release: “(Studio) Ghibli… was barely established in (Japan) and all but unknown elsewhere.”

For Aquib Hussain, FX TD at DNEG Animation, “One of the most underrated aspects of Grave of the Fireflies is its pacing. I don’t see many people talk about it, but right from the beginning, we already know the tragic fate of the two main characters. And yet […] every moment that follows is filled with such contrast (colourful vibrant animation over a dark truthful story) – it’s tender, hopeful, and even beautiful in its tragedy.

He adds: "The bond between the siblings is genuinely touching. I also appreciate how the film doesn’t shy away from using fantastical elements, especially in its animation."

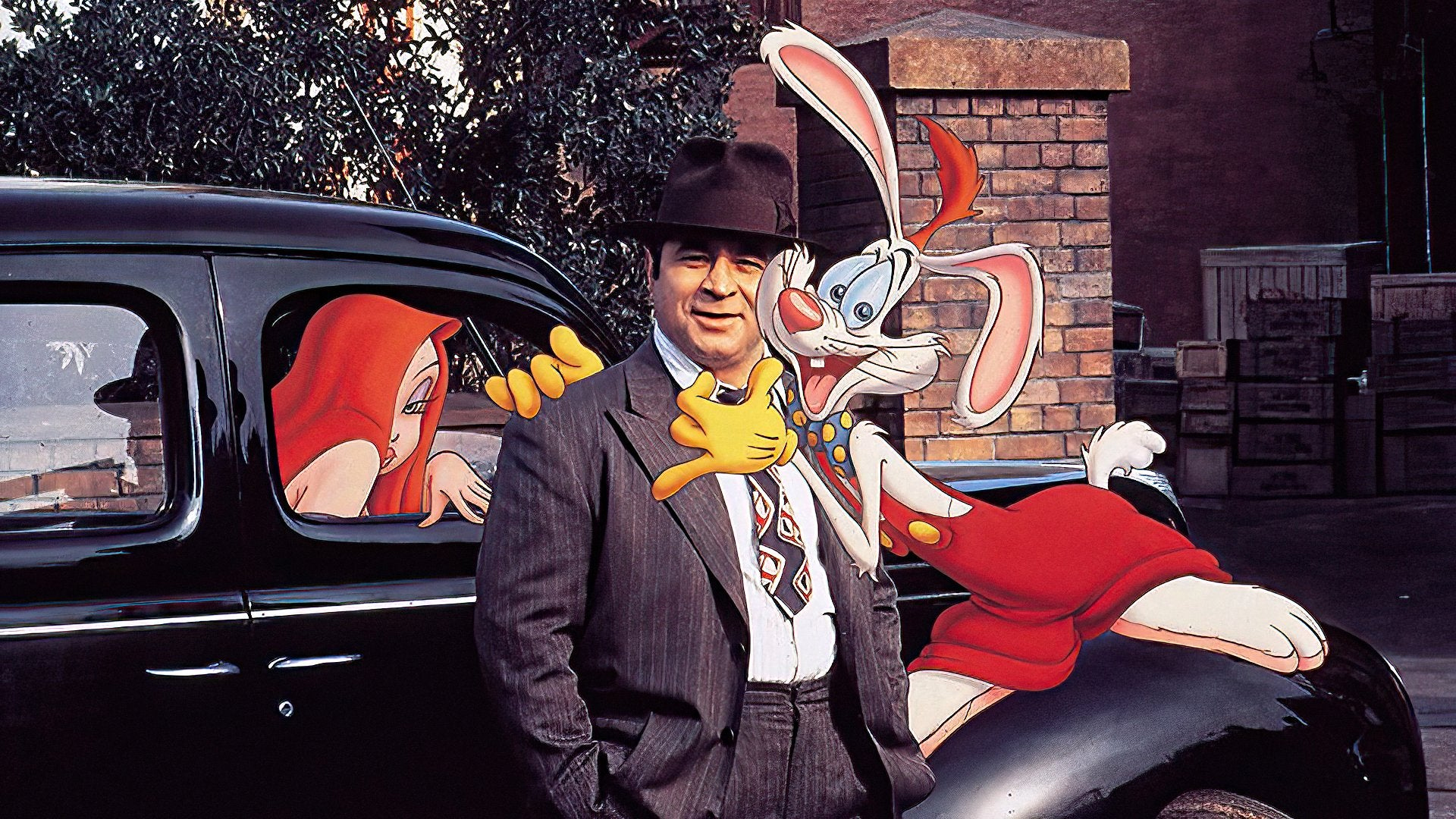

11. Who Framed Roger Rabbit?

It was the film’s executive producer Steven Spielberg who suggested that Roger’s mouth resemble the mouth of Thumper the rabbit from the Disney film, Bambi.

One of the quintessential fantasy movies of all time, and one of the most studio spectacles of the 1980s, Who Framed Roger Rabbit began life as a novel by Gary Wolf entitled Who Censored Roger Rabbit ? Roger Rabbit is a fusion of so many classic American cartoon character design elements.

For Kayn Garcia, Animation Supervisor at Framestore, they recall that “Growing up on Looney Tunes and Disney morning cartoons, Who Framed Roger Rabbit was a huge inspiration, bringing together all these classics into a slapstick modern day noir film. It definitely sparked my intrigue in integrating fictional characters into a live action setting. Techniques used in this film for intertwining Roger Rabbit into the real world still influence us today.”

For James Farrington, Rough Layout Artist at DNEG Animation, his comments comprise his memories of working on the film: “I got hired as an assistant animator (on Roger Rabbit) and you were teamed up with an animator who did the rough keys and planned out the action."

He adds: "I would then take his keys and clean them up, (put them "On Model") then do the major breakdown drawings between the keys and do the charts for them to be sent to the floor below for in-betweening. This was the traditional Walt Disney Studio way and whilst working as an inbetweener I got to work with some of the best animators of the time.”

12. The Little Mermaid

Animator Glenn Keane treated Ariel’s hair as a character in its own right as a way to express emotion and thought. Writer and performer Sheri Stoner worked as a live action reference model for the animators.

In 1989, the Disney Animation Studio enjoyed huge commercial success with their take on Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tale. A cel-animated piece, that effectively launched a new era of Disney animated feature film production, The Little Mermaid enjoyed huge popularity and is now considered a classic of the studio.

For animation scholar Peter Kunze, he writes on Fantasy Animation.org that, “the Disney Renaissance was part of a much larger and longer revival in interest in animation across film, television, video games, and emerging digital forms in the 1980s and 1990s […] The Little Mermaid deserves credit for sparking renewed interest in feature animation and film musicals in Hollywood,”

Start animating yourself with our Blender tutorials and read our list of Procreate tutorials for advice on character design.

James has written about movies and popular culture since 2001. His books include Blue Eyed Cool: Paul Newman, Bodies in Heroic Motion: The Cinema of James Cameron, The Virgin Film Guide: Animated Films and The Year of the Geek. In addition to his books, James has written for magazines including 3D World and Imagine FX.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.