Unreal Engine and Unity are "the best training tools that I could possibly imagine," says Dune's cinematographer

Zooming in on virtual new filmmaking trends.

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Five times a week

CreativeBloq

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Once a week

By Design

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Once a week

State of the Art

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Seasonal (around events)

Brand Impact Awards

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Even with the dominance of digital photography, there is still a push to reflect the grounded philosophy from the film era – though this traditional approach is changing as several generations have grown up with a video game console in their hands, and smartphones have led to the global proliferation of cameras.

As a result, the criteria for what is considered to be believable and attainable imagery is being redefined, and causing a reshaping of the cinematic visual language. We've heard how game engines like Unreal Engine 5 are the future of filmmaking and have seen first-hand how LED Volume Stages can be used. And we've seen the reverse, when video game Harold Halibut adopted film techniques and the forthcoming Senua's Saga: Hellblade 2 is matching Hollywood for mocap and fidelity. So is the convergence of game tech and filmmaking a good thing? Let's ask some leading cinematographers.

"There's got to be a knock-on effect from people growing up with that sort of world," observes Oscar-winning cinematographer Greig Fraser who shot the pilot for The Mandalorian, which sparked the virtual production craze. He's since gone on to work on Dune series, The Batman and The Creator.

Greig adds: "I don't think every film in 25 years will be a first-person shooter but we're seeing that with films, like The Revenant, which is immersive and wide angle. I believe that there's going to be a place for a lot of different styles without a shadow of a doubt."

In the past, getting access to camera equipment was an expensive proposition, but game engines such as Unreal Engine 5 and Unity are making the virtual alternative an affordable and accessible option. "The best training tool that I could possibly imagine would be someone being proficient in these programs where they can experiment and play to their heart’s desire," believes Greig.

Greig continues: "And then apply what they're learning to the real world, but they've also got a huge base of knowledge when they get into the virtual world, and know what’s possible and what’s not possible."

Tools in virtual cinematography are appearing in the real world. "FPV drones can fly through the legs of people and into bowling alleys," Greig adds. "They can do things that a camera has never been able to do."

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

VR scouting is also an indispensable tool. Greig explains: "You can be in a set months or years in advance without the set being built, and be talking about what you would be exploring the day before the shoot. You can refine the parts of the set that you need and what the shots are. On the day, you are able to get through the work quicker and with more precision."

Greig reflects: "And it costs peanuts compared to a day on a film shoot, where you're spending hundreds of thousands of dollars every single day you're standing there. Of course, on the shoot day everything decided on the VR scout can change, but it provides knowledge and information that makes you more prepared."

You can be in a set months or years in advance without the set being built, and be talking about what you would be exploring the day before the shoot

Greig Fraser

Visual continuity has become an issue as a growing number of shots are being digitally created and augmented in post-production by visual effects artists. "Everybody has to understand the limitations of their skill base," states Greig. "The cinematographer has to know instantly why it isn't working. 'The lens is too close. The lens is too wide. The light is too bright. The backlight doesn't match the previous shot.' As tricky as it might be, the best practices are keeping the production designer and cinematographer involved in the entire process as best as possible."

Greig continues: "Up to now we've got through. Films look good. Thankfully the directors have probably learned enough of the visual language that they can help with that. But in order to take the pressure off the director there should be a system worked out whereby there are reviews with the cinematographer."

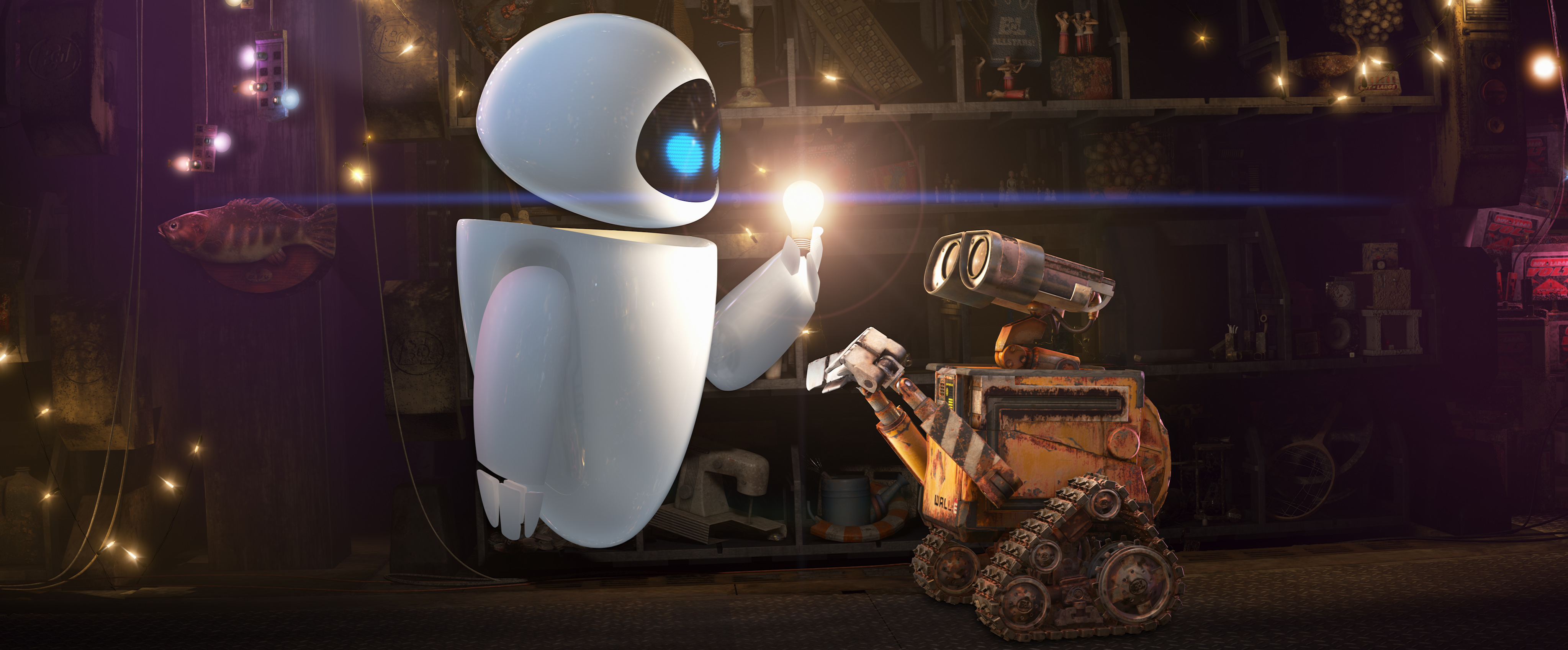

Animated projects can benefit from the expertise. "When you have films like WALL-E, for which Roger Deakins helped to supervise the cinematography, that's fantastic," Greig says. "The level of precision and artistic choices on that film is fantastic. They made such a clever decision to employ someone like Roger, who all he has done for 30-plus years is shoot scenes. It's the same for me over the last 15 years. When you're trying to make a scene its best, hire those people who have done it before, because they can make it good quickly."

Nothing is free within the virtual realm. "Happy accidents are rare in a computer but is what helps to ground some of the imagery, so we work hard to recreate them," notes Ian Megibben, director of photography for lighting at Pixar.

He continues: "It’s almost the opposite. The tools are so flexible that you have infinite possibilities. It's more of a study going, 'How do we limit all of those options so that we create a character out of it?' The characteristics of the Lightyear or WALL-E lens, or whatever show we're working on. If you use every colour in the crayon box it can start to lose its focus."

The type of movie being made influences the style of aberrations, such as camera shakes. "WALL-E had a heavy documentary camera shake feel, especially for the first third of the film, which was designed to fit in the world and look we were going for," notes Jeremy Lasky, director of photography for camera at Pixar.

"Lightyear has camera shake too but in a different way. It's there all of the time but subtle. It doesn't feel like we have lockset pixels at any one time. There is always a little adjustment happening some place to keep the image fresh. And when we put it in, we wanted to make sure that the animation quality of the camera was consistent in the world with the animation quality of the characters and effects.

"Meaning if you have camera shake on a film like Toy Story, those characters behave in a cartoony way; though you want the shake to feel realistic, you don't want it to take you out of the film by introducing a new kind of motion you haven't seen somewhere else."

Being a member of the 3D story team on Star Wars: The Clone Wars, where traditional storyboards were replaced with 3D animatics, taught Ira Owens, a cinematographer in the video game industry, that wide shots should be beautiful and epic, medium shots have to be clear and concise, and close-ups are for punctuating the moment.

"Because gaming has changed so much over the years to be more cinematic in its storytelling, those skills allowed me the opportunity to cross that bridge of being in animation, which is primarily cartoony but has gotten a lot more action oriented over the years," believes Ira.

Ira adds: "When you're learning how to tell a story there is film language, screen direction, and the camera. How does a long lens operate versus a wide lens? It was a learning curve. I watched a lot of films and asked myself, 'I like this shot. How did they get it?' I would research that."

"The game controller becomes the camera that can pan, pitch and crane around a roughed-out or completed setting. "I work with the environment and lighting teams directly in the game and can change the lenses quickly to see what looks good for different characters based on their appearance," says Ira.

Storyboards, concept art and previously shot live-action footage influence camera and lighting decisions. Ira says: "I pull everything together before I make any final decisions. Even when I go through and do cameras for a cinematic, there are a lot of different people who are part of that conversation."

Storytelling has become more sophisticated. "The Last of Us is a fantastic example where the game was cinematic and had this tone and pacing that wasn't constant action," observes Ira.

Ira continues: "There are moments to breathe. Now you watch the TV series, which has been beautifully done. Cinematography in games is 100% being influenced by live-action film and the marriage is there now. If you're using Unreal Engine all of those bells and whistles are available. I enjoy using these 3D tools not just in the practical sense of exploring how we’re going to schedule this and build it, but to figure out the shots and pacing, being intentional with my shot choices, and also being clear on how I tell the story."

Virtual production has become a victim of its own success. Ira says: "It's being used so much, but where is it being used in a way that complements the story and all of the elements? House of the Dragon is beautifully done. Personally, I always want to bring a grounded reality to the cameras. Not everyone feels the same way. Some people in video games want to explore a more immersive experience."

And adds: "There is certainly the VR aspect as well. The God of War series shattered any expectations that it needs to be a cinematic cutscene that’s shot to shot. The God of War game is a continuous shot every time; it's a cinematic and they pulled it off. It's incredible and immersive. There are opportunities to tell a story in a different fashion.

Before finally saying: "Technology allows a lot more wiggle room, but still the storytelling has to be grounded in a reality. Games enable you to push what that is and how you're going to tell that story. What I'd hope that anyone would have to say about being a 3D cinematographer is that our first and foremost goal is to tell a story in the most entertaining way."

This content originally appeared in 3D World magazine, the world's leading CG art magazine. Subscribe to 3D World at Magazines Direct. If you've been inspired, read our guide to the best laptops for game development and best drawing tablets, and start creating.

Trevor Hogg is a freelance video editor and journalist, who has written for a number of titles including 3D World, VFX Voice, Animation Magazine and British Cinematographer. An expert in visual effects, he regularly goes behind the scenes of the latest Hollywood blockbusters to reveal how they are put together.