Digital Domain creates incredible sci-fi world for hit movie

Discover how the leading VFX facility had to change its pipeline in order to simulate the holographic effects in the sci-fi blockbuster, Ender’s Game.

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Five times a week

CreativeBloq

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Once a week

By Design

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Once a week

State of the Art

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Seasonal (around events)

Brand Impact Awards

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

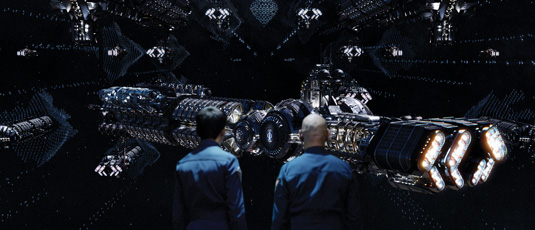

Far in the future an extraordinary young boy, Andrew 'Ender' Wiggin, is trained for battle. In a virtual environment called the Simulation Cave, Ender participates in a training programme that he believes is a simulation, but is in fact a series of real-world battles, after which Ender and his fleet of fighter ships emerge as the victor over the alien Formics.

Under the guidance of Digital Domain's VFX supervisor Matthew Butler and associate DFX supervisor Mårten Larsson, the details of this incredible world were filled in, involving real-world physics, camera moves within the environment, and panning and zooming as Ender controls his point of view.

"That can confuse an audience, so we needed to have graphical overlays in 3D space to communicate that Ender is informing the point of view; manipulating these graphics in gestures. We see cause and effect and understand that he's driving what he's seeing," says Butler.

The blackness and vastness of space also presented visual challenges to the Digital Domain team. How do you light ships when there is no light, for instance, and how do you convey size when there is nothing to compare size with?

According to Larsson, "the big challenges were how we put big spaceships around Ender and not make them look like miniatures, especially because we couldn't use atmospherics. We solved that mostly with camera moves and by not moving things around too much."

A big challenge was how we put big spaceships around Ender and not make them look like miniatures

In real-world measurements, each ship was roughly the size of a jet fighter but it can be hard to communicate scale when there's nothing to compare the object with. "If you see a large spaceship flying over a city, you know how big it is in comparison to the buildings," says Larsson.

Finding flight

Digital Domain accomplished a sense of scale through several approaches. First, they made sure the larger ships didn’t change direction too quickly. Another trick was when introducing new spaceships, they entered above the camera viewpoint to make them appear larger. They also would occasionally bring the camera close to the ships, or fly a fighter close to the foreground, to remind the audience of the scale.

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Screenwriter and director Gavin Hood was clear from the beginning that he wanted the movement of the Formics to be distinguishable from the behaviour of the International Fleet (IF) drones that were tasked with protecting the larger ships. While the IF drones flew in a more regimented military style in large formations that were tightly controlled, the Formics flew in an organic flocking behaviour similar to the murmurations of birds in the natural world.

To inspire the Formic flocking, Hood had the Digital Domain team review references of flocking starlings, and for the IF fleet, the team sourced inspiration from the University of Pennsylvania's footage of quadcopter formations and drones in synchronised flying.

The ships that were close to the camera, following the required flocking or regimented behaviours with added offsets and delays, required specific art directing and were mostly hand-animated in Maya. Wider shots and larger battles numbering millions of ships required a far more automated solution handled in Houdini.

Maintaining a rigid geometric shape of IF drones clustered around the larger ships didn't sell. "We realised early on," says Larsson, "if you don't build in some kind of lag it doesn't look natural, it doesn't have any individual motion."

It took several stages of testing to find the most efficient and satisfying solution, tools that could animate the overall desired shapes the drones needed to maintain, with a Houdini system on top to add real-world physics through a bit of lag and noise to the cluster. "If the shape was moving too fast they would struggle to keep up, but keep the regimented flying behaviours just to make it look a little more organic."

Organic flocking

To recreate the Formics' organic, swarming movement - similar to flocking birds - Digital Domain's first thought was to use the crowd simulation software Massive. However, the team quickly realised the amount of set up to bring it into the current pipeline would be prohibitive, and that it didn't manage the agents' murmuration movements as easily as they'd hoped.

Instead, they based their process on established simulation techniques and behaviours from 'Flocks, Herds, and Schools', a paper by Craig Reynolds on the movement of groups of animals. It wound up being simpler and easier to skip the step of adding an extra package and just do it in Houdini. Once Digital Domain implemented its own system of flocking algorithms, it was ready to tackle the next issues - animating, lighting and rendering swarms of ships that numbered into the millions.

In an instance

Thankfully Digital Domain only needed one model for each style of ship - one Formic fighter and one IF drone. This meant the team could minimise RAM usage while increasing both the number of ships simulated and rendered on screen at the same time.

"We could use all sorts of instancing tricks, it simplified our pipeline quite a bit," says Larsson. "We didn’t need to keep track of what type of ships belonged to each point since all we needed to know was whether it was a Formic sim or an IF sim. We also took advantage of instancing geometry at render time to keep RAM usage down."

The instancing was particularly helpful for around ten wide shots, which showed what Digital Domain dubbed 'superflocks' numbering between 20 and 100 million ships. When the camera was that far out, the ships in the far distance were rendered as points.

I think we had frames that were stuck on 30 or 40 hours to render, but that was the extreme case

According to Larsson, render times remained reasonably low for most shots. "We had some render times that spiked every now and then for the superflocks, I think we had frames that were stuck on 30, 40 hours, but that was the extreme case. We never simulated that many at the same time - I think a few hundred thousand was our maximum simulation."

Using layers

Of course layers are also an integral part of keeping render times down. "For the flocking we broke it up with distance from camera, or if there was an isolated flock around a specific ship we would simulate that on its own," says Larsson. In some cases, Ender's view passes right through the flocking simulations.

There are shots where the camera lands right in the middle of the battle as the Formic ships approach by the thousands from behind, the camera pans around and the swarm of ships blast past. There were big, pullout shots with the camera sitting inside the swarm then pulling out to a side-view, wide-angle shot showing the movements of close to 100 million swarming ships.

The methods for wrangling so much data were fairly standard, but had to address requirements unique to Ender's Game. "In some cases," says Larsson, "we split front to back when we had too many agents or Formics in one sim; we would spilt it up according to distance from camera: we would simulate what was further away separately from things close to camera to have more control."

Digital Domain carried out tests to simulate as many ships as possible on screen at one time and, once the times became unacceptable, they would scale back and start breaking it up into layers. They found that by starting with the carrier ships, the flocking simulations could use them as collision objects and would know where the ships were in space, and so could react appropriately.

Interactive lighting

Lighting in the blackness of space also created a daunting challenge Battles were taking place near and far, ranging from the centre of undulating swarms to millions of dots in the distance, which was difficult to make readable. Theoretically, the shadow side of the reflective ships were lit by just one sun and appeared as black as the background, visually cutting the geometry in half.

Although high contrasts were softened by bounce light radiating, as if there was a planet close by, the lighting contrast was still too high. "We wanted to capture the interactive light, any time we had explosions, anything firing," says Larsson. "It's something we always try to do, but we really had to pay attention here."

We wanted to capture the interactive light, any time we had explosions, anything firing

It is common to add interactive lighting, but it became particularly important on Ender's Game since bright explosions in areas of shade tended to look odd. A pipeline was set up to handle any effects-driven explosion or tracer fire.

There were several different setups: for explosions, Digital Domain could generate and send point lights to the lighting department for interactive lighting. There were setups that generated iso-surfaces from the explosions that would then be exported as VR meshes over to V-Ray, where the explosion was precomped and colour-corrected, and then the comp was published with the iso-surface mesh of the explosion, projected back out onto the mesh and used as a geometry light.

"It was quite a bit of work to put into the pipeline,” says Larsson, "but it paid off because it gave us a fully automated way of doing a lot of interactive lighting when there were tracers flying and hundreds of Formics shooting, lit up by their own tracers and hitting the carriers.

"We have a lot of simulations and explosions that are really cool, but I think the thing that stands out the most is the complex behaviour, both destruction simulations and flocking, combined with the lighting and interactive lighting. It makes it all sit in the same world."

Words: Renee Dunlop

This article originally appeared in 3D World issue 176.

The Creative Bloq team is made up of a group of art and design enthusiasts, and has changed and evolved since Creative Bloq began back in 2012. The current website team consists of eight full-time members of staff: Editor Georgia Coggan, Deputy Editor Rosie Hilder, Ecommerce Editor Beren Neale, Senior News Editor Daniel Piper, Editor, Digital Art and 3D Ian Dean, Tech Reviews Editor Erlingur Einarsson, Ecommerce Writer Beth Nicholls and Staff Writer Natalie Fear, as well as a roster of freelancers from around the world. The ImagineFX magazine team also pitch in, ensuring that content from leading digital art publication ImagineFX is represented on Creative Bloq.