Why Dawn of the Planet of the Apes was a triple challenge for Weta

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Five times a week

CreativeBloq

Your daily dose of creative inspiration: unmissable art, design and tech news, reviews, expert commentary and buying advice.

Once a week

By Design

The design newsletter from Creative Bloq, bringing you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of graphic design, branding, typography and more.

Once a week

State of the Art

Our digital art newsletter is your go-to source for the latest news, trends, and inspiration from the worlds of art, illustration, 3D modelling, game design, animation, and beyond.

Seasonal (around events)

Brand Impact Awards

Make an impression. Sign up to learn more about this prestigious award scheme, which celebrates the best of branding.

This article is produced in association with Masters of CG, a contest for creatives in partnership with HP, Nvidia, and 2000 AD. Check out the shortlisted entries here.

It's a longstanding cinema cliche, deftly parodied in the recent 22 Jump Street, that movie sequels are bigger, noisier and more spectacular than their predecessors. And Dawn of the Planet of the Apes, the follow-up to 2011's Rise of the Planet of the Apes, certainly fits that mould.

The ramping up of the action here is of course dramatically justified; while Rise was the scene setter, Dawn is where the war between simians and humans finally comes to a head. But that was little consolation to animation supervisor Dan Barrett at Weta Digital, who had three big hurdles to leap this time around.

- While the apes in Rise had been mute (with a dramatic, single-word exception) in Dawn, they would talk.

- There would also be an awful lot more of them: the first film had largely been centred around one CG character, Caesar, but this time around there would be a great deal more ape-crowd scenes.

- The film would be shot in 3D – rather than being converted from 2D in post. And that posed clear challenges to a production that combined motion capture, animation and live action to an intensely complex degree.

Watch the film, though, and you can't see the join. So how did they manage to pull it off? We chatted to Barrett to find out...

01. The talking apes

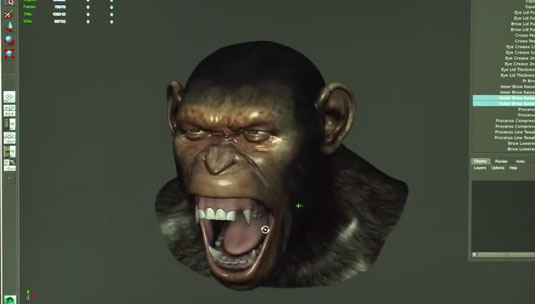

When it came to animating the apes' dialogue, the motion captured footage of the real-life actors was a good place to start, explains Barrett. "The structure of the muscles on the face of a chimp are very similar to a human," he points out. "So we didn't have to greatly change our paradigm when it comes to making the face puppet, for an ape. We used all the same muscles and worked from there."

That only got Weta so far, though. "Obviously the facial structure of an ape as a whole is very different; the bone structure is very different. So while the muscles lie in relatively the same positions, you still have to run over a substructure that's different. Which means there's a fair bit of translation that occurs there."

Central to that translation was steering a fine line between looking too human and too ape-like. "If your actor is a human, then it can be difficult for an audience to accept those sounds are being made by a chimp," Barrett points out. "You can necessarily just go 'full chimp' if the sounds aren't 'full chimp'."

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

That meant the face puppets from Rise would have to be overhauled accordingly. "So we said: 'Let's look at the actors, let's look at their lips and see if there are things we can do to make dialogue more believable.' We had to be careful not to stick a human mouth on the front of a big muzzle, you know – it would look kind of weird.

And the same was true in the opposite direction. "For instance, we had a shape saved called a 'funneler', which on a chimp is the lips being pushed forward into an 'oo'. But that didn't look right with spoken human dialogue. So we needed to create an alternate version – sort of a 'human funneller' – that both sat nicely on the face of a chimp and looked realistic with dialogue."

Throughout the process, the animators would look closely at the actors, especially the eyes of the actors, to ensure they could get that performance through to the CG character. "We made sure we had certain details from the actors in our chimp. Elements of Andy Serkis's eyes are in Caesar, for instance. So for the dialogue that's another thing we did – we looked at how the lips moved and the kind of shapes that they made and feathered those in as best we could."

02. Ape crowd scenes

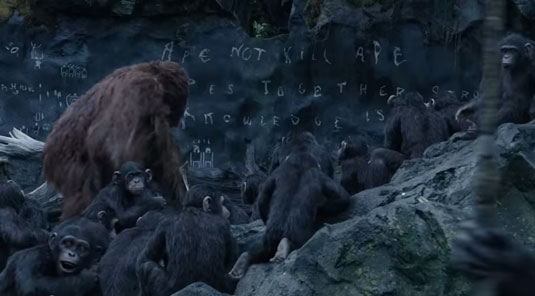

The appearance of multiple CG apes at any one time was another challenge to Weta, adds Barrett. Although it wasn't all stressful. "In fact, in many of the village scenes it was quite a fun thing," he admits.

"The director Matt Reeves wanted to ensure he had this depth of realism to the ape village," he explains. "And so a lot of the stuff we captured was just us sitting down and saying: 'OK, well what goes on – what does a day in the life look like in an ape village?' It's good to have a bunch of actors who are throwing in ideas, and they can be fun sessions."

Things got challenging, though, when it came to populating these locations. "Take, for example, when Caesar returns to the village. We've got this 'day in the life' going on, and there's this slight surge of apes towards Caesar. As soon as you start introducing that amount of travel it can get difficult. If you're not careful, for instance, apes can quite easily 'walk through' other apes, so it's an onerous task to keep all the interactions working properly."

A lot of that work is done by a wing of the animation dept called the motion edit team, Barrett explains. "They're animators, but they're not key-frame animators, so they're dealing with motion capture data. And so those scenes are a testament to the hard work and often great ideas of the motion edit team."

Keeping all the apes visible also becomes a huge demand on computing resources, Barrett adds. "Things can get very slow and bog you down for a while; it becomes quite the beast when it comes to rendering."

But Weta resisted the temptation to cut corners. "We didn't tend to drop down resolution and detail on our apes when we went for a wide crowd scene," he stresses. "We keep the same high resolution, same fur grooms, they've all got fingernails and wrinkles and so on. It slowed us down, but it really helped to make it feel natural."

03. Shooting in 3D

Stereo 3D may look amazing, but it can make the life of an animator a tough one, Barrett says. "When you're talking 2D, or even post-conversion, there's a certain amount you can get away with. If you ever strike any little issues and you can't quite get a framing that a director might be looking for then you can kind of cheat things, you know, you can drop a shadow and no one's going to be any the wiser."

Shooting in stereo, though, there's nowhere to hide. "You have to be at the exact depth. Say if you're replacing an actor, you have to be at that exact depth with your ape, otherwise it's going to be obvious when the viewer puts their glasses on."

On Dawn, the biggest challenge in this respect was apes on horses, Barrett reveals. "There were some very tricky shots, and I think the success of a lot of those shots is testament to the incredible work that the camera department did here.

"If we needed to take Andy off a horse – and the horse was in the plate and we wanted to put an ape where Andy was – then we needed match-move work and rota-motion work from the camera department that was perfect. As I said, there's nowhere to hide, so we needed to know the exact depth of that horse so that we could place our ape on them. And then obviously there's a lot of spectacular paint out work in situations like that, where you have to get rid of the actor."

Another tricky sequence was the one where Caesar is loaded into the landrover and taken to his old house, where he's being carried. "Again, Andy [Serkis] was in the plate – it was the only way to get a great performance from those who were carrying," Barrett explains. "Unless you have a wrist that's being gripped, unless that's in exactly the same space that Andy was in, it's going to look wrong. You're going to see an intersection, and so it's a whole new world of challenges."

Tom May is an award-winning journalist specialising in art, design, photography and technology. His latest book, The 50 Greatest Designers (Arcturus Publishing), was published this June. He's also author of Great TED Talks: Creativity (Pavilion Books). Tom was previously editor of Professional Photography magazine, associate editor at Creative Bloq, and deputy editor at net magazine.