A beginner's guide to displacement and bump maps

See how these maps can give your 3D models extra relief and detail.

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Five times a week

CreativeBloq

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Once a week

By Design

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Once a week

State of the Art

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Seasonal (around events)

Brand Impact Awards

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

If you’re new to CGI, you may feel that there are far too many tools to choose from in a dizzying array of software. By breaking everything in CGI down, I want to arm artists with the knowledge of which tool is best. With this in mind, let's explore materials and shaders by looking at bump and displacement maps. But first, let's look at why these maps are different to normal maps.

What's the difference between bump maps and normal maps?

In a previous article I looked at normal maps, which are a type of image map used to add extra detail to your models.

There are other image map types for adding details and relief to your 3D art: bump and displacement maps. These both use black and white imagery to create relief data for a model, making bump and displacement imagery far easier to create and manipulate in any 2D painting application when compared to the complex three-colour arrangement of normal maps.

The differentiation between bump and displacement maps is in how they display the relief.

How does bump mapping work?

Bump maps are one of the oldest form of image map types (normal maps are derived from bump maps), and have been used for decades to add surface relief to models. Bump maps are not very resource-intensive, making them a popular choice for a wide range of relief work.

The catch with bump maps is that they cannot render corner or edge detail, which makes them problematic in certain situations, for example adding brick detail to a corner edge. Bump maps are by far the easiest type of relief image to manage as they work with practically any surface, no matter the geometry.

What does a displacement map do?

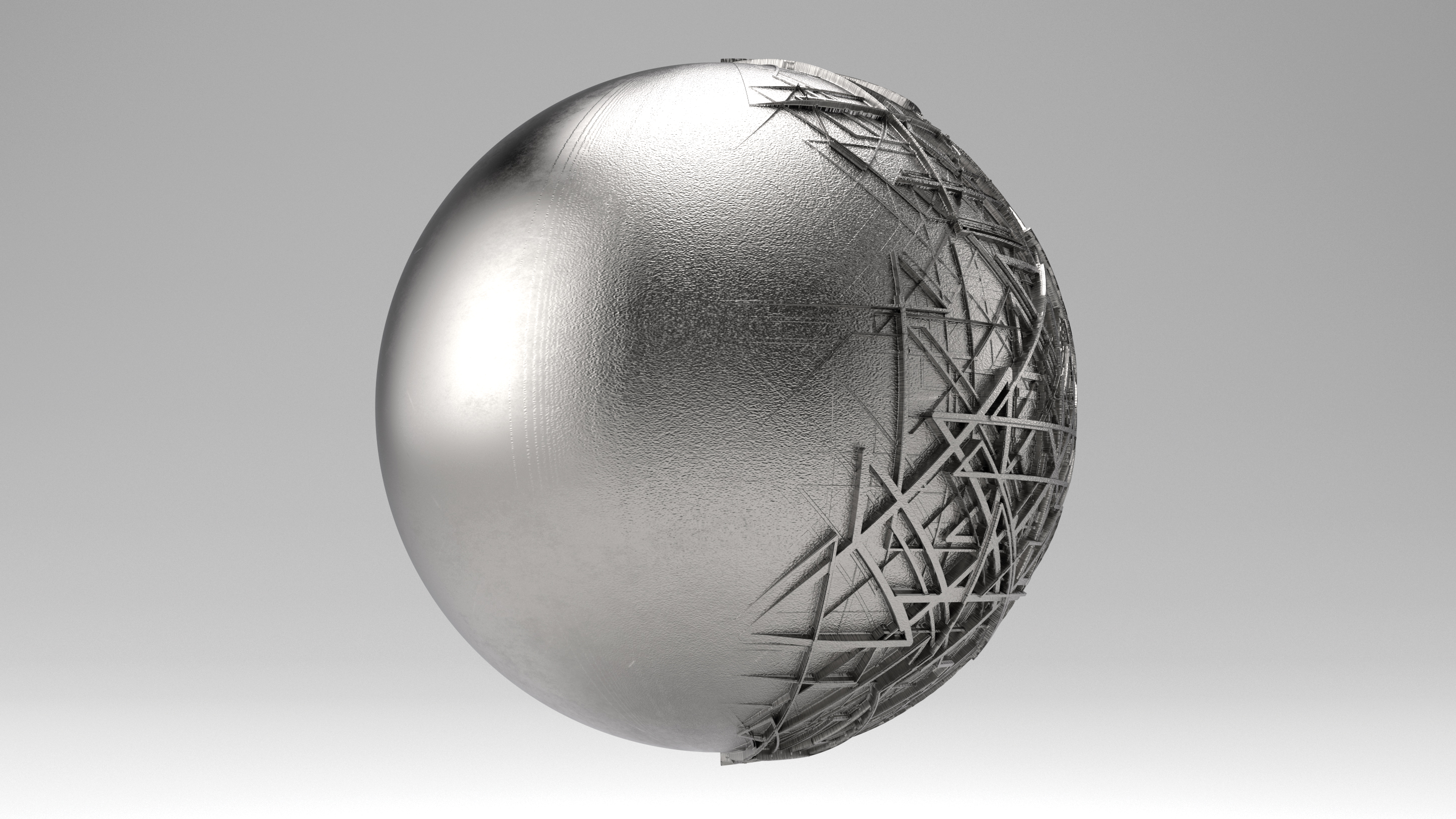

Displacement maps, although they can be derived from the same type of image as a bump map, are much more powerful. They can truly deform geometry up to and including edge detail, making them ideal for a much wider range of uses such as terrain creation (sometimes a displacement is called a height map for large-scale deformation) and detail modelling.

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

The reason that displacement maps are not as commonly used is that they can be computationally intensive and they tend to like high-resolution geometry to work with, which can make them less than ideal for some tasks.

Either way, understanding bump and displacement maps will enable any artist to add detail to their models more quickly and intuitively than through other image-based methods.

When to use a bump map

At its simplest, bump mapping only modifies the surface of a piece of geometry, whereas displacement mapping is actually altering the geometry. Bump maps are great at adding a lot of low-relief detail on low-polygon objects, so a one-polygon wall could show hundreds of bricks thanks to bump mapping.

It can be an issue when edge detail needs to be shown, as bump mapping does not work with side detail – it only shows the true underlying geometry.

When to use a displacement map

Displacement maps are a hugely powerful technique as they can intuitively allow model detail to be added with a simple greyscale image. A perfect example is when they are used as a simple method of creating the height data for a landscape.

As displacement maps (also sometimes known as height maps) are modifying the underlying geometry, they need higher-resolution meshes to work with than bump maps, which can make them slower to work with. But they can produce stunning results.

Combine maps

Bump and displacement maps can be used in conjunction with one another. For example, when using displacement maps to add true relief to a landscape, a bump map can be used to add additional noise to the surface.

This takes some of the computational weight away from the displacement map, allowing faster performance for negligible image loss. Understanding the properties of when and where to use bump and displacement maps can radically improve models and scenes.

Height differences between maps

Both maps display height differently because of the underlying science behind each. However, this can also be true of the software being used. Displacement maps especially should be double-checked in the final render software when brought in from an external painting programme or other render software; there can be differences between how they are displayed, especially with different levels of geometry. Never assume anything until it has been tested for the specific scene or model required.

Create your own bump and displacement maps

One of the best things about bump and displacement maps is that visually they make sense, with white areas usually denoting the highest areas, black the lowest and 50% grey equalling no change.

This means that while there are applications like Bitmap2Material that can make a good guess at creating relief, it is sometimes better to use a 2D image application. Using a high-pass filter can be an excellent way to get started in creating a relief map which can then be painted into using traditional 2D painting techniques.

This article was originally published in issue 238 of 3D World, the world's best-selling magazine for CG artists. Buy issue 241 or subscribe to 3D World here.

Related articles:

Mike Griggs is a veteran digital content creator and technical writer. For nearly 30 years, Mike has been creating digital artwork, animations and VR elements for multi-national companies and world-class museums. Mike has been a writer for 3D World Magazine and Creative Bloq for over 10 years, where he has shared his passion for demystifying the process of digital content creation.