PixelPyros creator shares why he loves open source

Seb Lee-Delisle on coding interactive digital fireworks.

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

"Introduce myself?" Seb Lee-Delisle smiles, laughs and fidgets in his chair. "You know how difficult it is to write your own profile, right? Well, currently, I'm a full time artist, building digital installations... building cool stuff with computers. I do some presentations and consultation all about creative coding. I try to help people explore creative uses of computers."

With a palpable sense of relief, he leans back in his chair and exhales. "That never gets any easier," he finishes.

When it comes to computer-based creativity, it's hard to think of anybody whose veins course with more caffeinated bits and bytes than Seb Lee-Delisle's. He's the man behind PixelPyros, a digital firework show that's toured the world.

Interactive pyrotechnics

Whereas fireworks rely on gunpowder, lasers power PixelPyros. They daub sparkling arcs and eruptions of colour onto a sixty-foot screen. The show is also interactive. Viewers – or rather, participants – launch fireworks by moving their hands in front of orbs of projected light.

"I like challenging myself, " he explains, considering the motivation behind PixelPyros. "I like challenging myself and creating things. Sure, a big part of what fascinates me is solving problems. If I see a Rubik's Cube that's messed up, it does my head in. I have to solve it. Building stuff is just a good feeling."

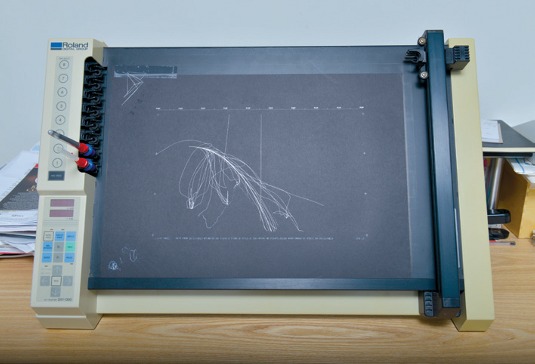

Other projects include Lunar Trails and PixelPhones. The former is an art installation built around a Lunar Lander gaming cabinet from 1979. As you play, a robot plots your movements on a giant canvas. The results are delicate, whimsical and strangely evocative of Bubble Chamber tracks.

PixelPhones is an open source platform that turns viewers' smartphones into pixels in a piece of art. Imagine a bright constellation map of all the smartphones in a theatre and you're on the right track.

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

So, when did computers first appear in his life? "Very early. My dad was a physics lecturer and he used to bring home computers for me to play with. I remember my brother and father had a really early computer called the Nascom. The memory was counted in bytes. Somehow they made a Space Invaders game for it. It was magic to me! I must have been nine or ten at the time."

"I remember first getting my hands on a computer when I was eleven. I learned BASIC on a little handheld computer. That seems futuristic, doesn't it? I think it was a Sharp. You could print stuff [to the screen] and make it beep. That was it," he laughs.

"The interesting thing is," he says, "I was always trying to make drawings, to make pictures, animations and games. Back then, of course, you had no choice but to learn programming. We didn't have Photoshop. My entire motivation for programming was to make pictures. And you know, today I just try to do the same stuff. I try to draw pictures with computers," he continues.

Computer music

Lee-Delisle also made music. "One of my friends ran an Amiga demo group Share and Enjoy. He chucked some of my music into a demo called Amazing Tunes II."

Despite his enthusiasm for computers, Lee-Delisle spent his 20s in a band. "That was my focus. It was possibly 1996. We wanted to make a big thing about being on the internet. So, I learned how to make websites for my band. We got a lot of coverage for being one of the first internet bands."

Sadly, the band didn't quite make it and its members needed to get jobs. Lee-Delisle took a job working for an e-learning firm. He says, "I was only freelance. I was doing lots of work in [Adobe] Director and then I learned Flash."

Flash games

Flash, it becomes apparent, was a real epiphany for Lee-Delisle. "I got really excited about Flash games. I really wanted to work for Kerb. They were a big Flash games house in Brighton. In the late '90s and early 2000s they were the bad boys of digital."

Lee-Delisle formed his own company and it went on to become the seed of Plug-in Media. "My first client was Kerb." Lee-Delisle explains. "I did maybe a couple of days a week for Kerb. I did some big projects. Something for Sony and a couple of games.

"One or two of my games won awards. One in particular [Stan James Free-Kick Challenge] had millions and millions of plays. It was hugely successful. And then I started to grow Plug-in a bit. I was doing some web design work too. It was only when I focused on games, things started working properly."

An artist called Dominic Minns joined Plug-in. He had contacts at the BBC so Plug-in started pitching for big projects. The BBC became a big client and Plug-in began specialising in making Flash games. "I guess this would have been around 2006," he recalls.

"And Plug-in just started growing and growing over the next few years until there were around 15 people there. We started doing some really big projects like [CBeebies] Big and Small."

For those who haven't frequented the children's BBC TV channels, Big and Small is a show about a friendly purple puppet and a bouncy orange one. For their efforts on the Big and Small Flash game, Plug-in won a BAFTA. Next came another BAFTA for work on the ZingZillas game, again for a BBC children's show.

Moving towards open source

As Plug-in flourished, Lee-Delisle began another dalliance. "I started speaking at conferences and contributing to open source. I was a member of the Papervision team, which was a 3D open source engine for Flash. I was starting to contribute to open source.

Despite the success of the firm he started, Lee-Delisle began to feel increasingly unfulfilled by it. "I began to realise that [Plugin] wasn't what I wanted to be doing. I was still doing the open source stuff and writing on my blog. I was sharing everything that I learned." As he recalls the memories, Lee-Delisle breaks into a full smile.

The look of joy recedes moments later. "I realised this was a bit of a conflict with the business. I think my partners got fed up when I was off in America all the time, running around doing conferences when they were doing all the work. I think it was a valuable thing to do but their point of view was..." He pauses, smiles and says: "different".

And so he parted ways with Plug-in. "I just decided to leave the company, which was really difficult. It's hard to get out of something you started, right? There's a lot of emotions flying around. It's like a divorce. But, it was the best thing to do."

Moving on to PixelPyros

Our discussion meanders its way back to PixelPyros and how it came into being. "It was a good few years ago. It was a side project. I'd seen Graffiti Research Labs had a project call Laser Tag. You could do graffiti tagging on a building with a laser... the tag would be projected on by a fairly low power projector [it's low power compared to the projectors we use but still four times brighter than most domestic projectors]. Maybe a 4,000-lumen projector.

"I got really excited. I'd never considered that you could project onto a building. I knocked up a demo in Flash. I projected it at a building and did webcam motion detection, all in Flash, and made some fireworks. It was a bit crap really, compared to the massive project it became."

Despite PixelPyros's modest beginning in 2007, Lee-Delisle found he couldn't shake off the idea. "Something about it really resonated with me. It captured my imagination."

Pyro problems

In 2012, Lee-Delisle set about building the project. "It was at the Brighton Digital festival. I started talking to people and got to know people who were good at getting Arts Council funding. Naively, I set upon this task to build this project. I applied for a grant and somehow got it and, honestly, everything went wrong!"

Throughout the four or five month production phase, the team had problems with finding venues, projection, getting insurance, health and safety, crowd control, evacuation plans, finding a production manager and hiring equipment.

But PixelPyros ran perfectly on the night. The show went on to tour the country, playing five dates at four venues and to tens of thousands of people.

Our chat moves on to open source, which is a topic close to Lee-Delisle's heart. "I wouldn't be able to do any of the work I do if it weren't for open source," he tells us. "LunarTrails makes massive use of Processing and Arduino. PixelPyros is built on open frameworks and uses lots of contributions from people in the community."

He rocks back in his chair and continues. "You know people say to me all the time: 'why don't you monetise your work? Why don't you set up a business that sells PixelPyros around the world?' But, by making it open source, it releases my sense of custodianship... of ownership."

Intellectual property

Clearly, Lee-Delisle isn't a complete refusenik when it comes to the idea of intellectual property and ownership. He leans forward purposefully in his chair and says: "Now, sure. If somebody took the code and made a show exactly the same as PixelPyros I'd be annoyed. People should be able to share and benefit from it."

"I've had a few famous international rock stars sniffing around [PixelPhones]. One said if we're going to pay you to do this, we want to own it. I said 'no'. That's not the point of it.

"I've put a lot of my own time into this. I don't want somebody to own it. I don't even want me to own it. Syncing up all the phones in a room isn't original but it's not been done in this way before because it's really hard!

"I don't want other people to go through what I went through to remake it. I'd rather they used my stuff and then maybe they'd get me in to be a consultant. To me, that's much better business rather than me putting a patent on it and suing anybody who links up phones. That's bullshit. That's not what I want to be doing with my life."

Is PixelPyros open source? "The source for PixelPyros is all there for you to see on my GitHub. I haven't actually attached a licence to it yet because I can't really figure out what licence to give it! You can certainly look at the source but, I'm still figuring out the best way to license it."

Finally, we touch on side projects. Lee-Delisle says: "Starting a project is easy. Finishing it is the hard bit. If you actually finish projects it sets you apart from almost everyone else. People are just very unprepared for the amount of work it takes to finish a project.

"That's why I always say, if you're doing a side project, make it buildable. Make it small. It's better to finish a small project than start a really big one."

So what's next for the man who makes digital fireworks? "I don't know whether I should talk about this," he says, rocking forward in his chair and beaming. "I want to make a simulation of being struck by lightning. Not killing anyone, but I could make a really cool lightning effect with a laser."

Photography: Rob Monk

This article originally appeared in net magazine issue 251 (March 2014).

As well as Seb Lee-Delisle's appearance, Generate London will feature 15 other great sessions spread over two days covering web animations, performance, UX strategy, teamwork, product design, accessibility, conversational and adaptive interfaces and much more. There's also a full day of workshops on 20 September, and if you buy a bundle, you'll save £95. Reserve your spot today!