The art of making open world video games

Game world-building masters from Larian Studios, Techland, HoYoverse, Billy Goat Entertainment and CD Projekt Red reveal what goes into crafting your favourite places on PlayStation.

Open world design has dominated videogame settings for over a decade, and you can learn more about that legacy by reading our feature on the history of open world game design on PlayStation. However, more goes into building your favourite spaces than slapping Caspar David Friedrich’s painting ‘Wanderer Above The Sea Of Fog’ on the mood board.

When it comes to immersive worlds, we’ve never had it so good - read our Avatar: Frontiers of Pandora review for a artistic example. But also, recently we’ve crashed through the material plane of Faerûn, run through the zombie-infested streets of Villedor, duelled with Fatui Harbingers across Teyvat, popped wheelies all over New Island, and disappeared into the seedy underbelly of Night City. Losing ourselves in these spaces, we emerge to seek the insight of the master world builders behind them, asking what exactly goes into setting the scene.

“Above all else, immersion and engagement reign supreme,” says Tymon Smektała, the franchise director for Dying Light. “A vast world means little if players don’t feel compelled to explore its depths and uncover its secrets. It’s not just about filling the map; it’s about creating an experience that captivates players from start to finish.”

2022’s Dying Light 2 Stay Human takes place in a world nearly two decades on from a zombie outbreak, while also offering what remains a fairly unique means of getting around: parkour. In creating Villedor, situated somewhere in Europe, Techland built upon everything it had achieved with the previous game’s smaller-scale Middle Eastern city setting, Harran. Full of dilapidated structures and still-towering skyscrapers, Villedor has greater verticality – so much so that you’ll use a paraglider in addition to your own two feet.

Above all else, immersion and engagement reign supreme

Tymon Smektała, director, Techland

The sequel’s geographical shift was for a few reasons. For one, much of the series’ audience hails from America and Asia, so a European setting offers something novel. Villedor takes cues from real-world cities such as French capital Paris and “some mid-sized northern German cities,” as well as Techland’s Polish home city. (Villedor’s water towers are modelled on similar structures found in Wrocław.)

“As Europeans we’re good at all things European, then for our players Europe is this place which a lot of them want to visit but [don’t always have] the chance to. So we’re [inviting] them to our continent,” Smektała says, joking, “We just didn’t mention it’s full of zombies, hahaha.”

The secret design behind Night City

CD Projekt Red also hails from Poland, with studios in Wrocław, Warsaw, and Kraków, though Cyberpunk 2077’s Night City is far from that comfort zone. Expert environment artist Krzysztof Kornatka shares: “Since most of the team comes from Europe, a significant challenge was adjusting to the scale and characteristics of American settings.”

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

The team delved into books on Brutalist architecture, and exchanged Google Earth co-ordinates for sources of structural flair throughout California – Night City draws heavily upon Los Angeles, San Diego, and San Francisco. The team swapped photos of alleyways and air conditioning units, but their research didn’t stop at the United States. Kornatka adds, “We also drew inspiration from the layout of Japanese streets, especially how advertising is used there.”

Filtering these real cities through the lens of a far-future, technological dystopia, the goal was “to create a believable anti-utopian city, and divide it into very distinctive regions so that the player always knew where they were.”

Kornatka quips, “I don’t think I’ll surprise anyone by saying that superbly crafted worlds in movies like Blade Runner, Johnny Mnemonic, Judge Dredd, The Fifth Element, or Akira have all served as inspiration for me.”

Night City oozes style, though that alone isn’t what’s kept players coming back after an infamously difficult launch and many ensuing updates. Kornatka says, “I can create a very intriguing world with beautifully composed views, interesting architecture, and perfectly designed level layouts, but what am I supposed to do in that world once I’ve seen everything? Probably, few would even see everything if not for those events that act like a magnet, pulling players into previously undisclosed alleys.”

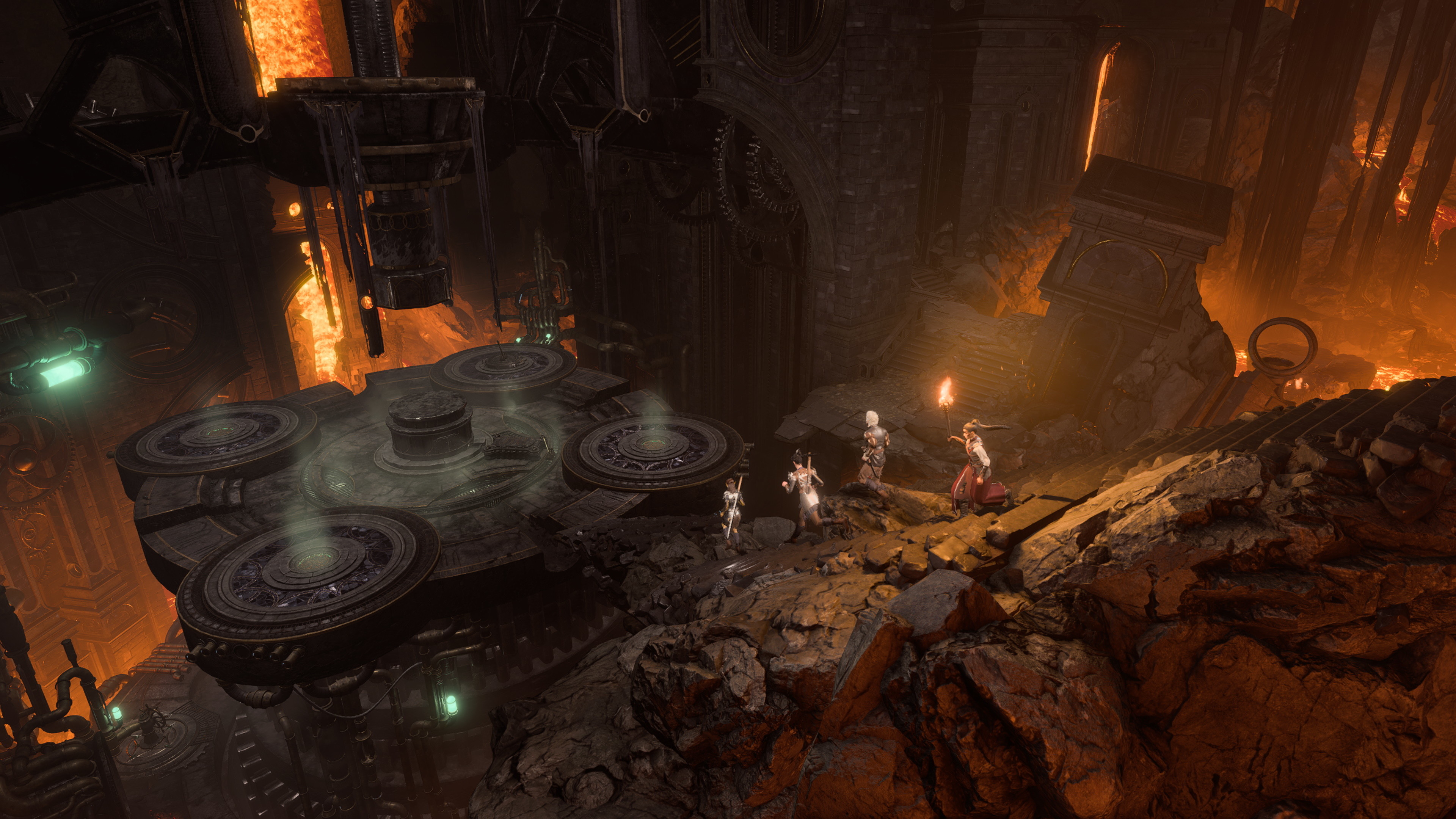

The hidden depths of Baldur’s Gate 3

To echo Techland’s Tymon Smektała, when it comes to ‘compelling players to explore a world’s depths and uncover its secrets,’ arguably few better understand the assignment than the team behind 2023’s hit RPG Baldur’s Gate 3. Larian’s corner of Dungeons & Dragons’ Forgotten Realms is split across multiple expansive maps with clear boundaries between them.

Cyberpunk 2077 is comparable not only for Night City’s distinct zones, its origins in a tabletop RPG, and the length of its development, but for how it tries to draw you in. Krzysztof Kornatka tells us he “absolutely” considers Night City an open world.

However, when we chat to Larian Studios’ world building director Farhang Namdar, he tells us, “Baldur’s Gate 3 is not really an open world game in the modern sense. It’s more of a curated open world.”

Every step along Faerûn’s Sword Coast has been deliberately designed. There are no random battles or suspiciously similar bases to clear, everything is placed for a reason – and that’s partly why Baldur’s Gate 3 took more than half a decade to make.

The crown jewel is the titular city, a huge, densely layered space which players finally reach in act three. In particular, the city’s design rests upon what Namdar describes as “one of the old Larian creeds.” He explains, “Every building needs a story, a secret, a cellar – preferably also a little garden but in Baldur’s Gate that didn’t make a lot of sense.”

Wherever you go in Baldur’s Gate 3, adventure awaits. Conversely, exploring Night City is more self-directed. Environment artist Krzysztof Kornatka explains, “Sometimes the player will be drawn by shouts or sounds, leading them to discover a beautiful vista of the city. At other times they might follow a mysteriously emerging alleyway between two monolithic skyscrapers to uncover an intriguing conversation that supplements their knowledge of the game and immerses them further.”

Kornatka concludes, “Whatever the case may be, it’s important for the player to feel rewarded. Depending on how much time they have to invest in reaching their goal, this reward should be greater.”

Larian’s Farhang Namdar puts it another way, “Players love walking into a seemingly innocent apothecary and ending up two hours and three puzzles later in a sacrificial chamber of a cult that murders giraffes.”

Worlds can tell stories

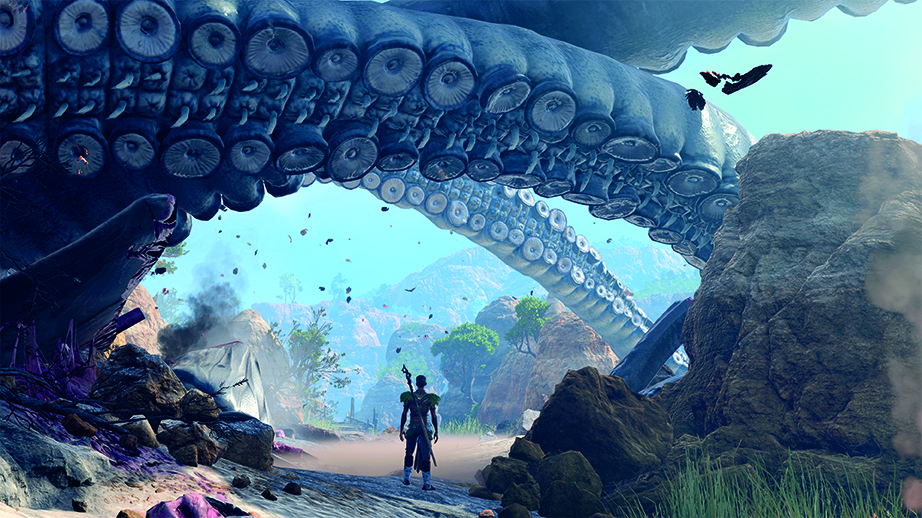

Metropolitan mammal murder aside, few starting points are as memorable as the tadpoled adventurer departing the Nautiloid crash site and finding their way through the wilderness in Baldur’s Gate 3’s opening act. “The journeys we create are always in service of the narrative,” Namdar tells us, “For the hero’s journey we always have to start humble and end as a hero.”

As you travel from the wilderness into the Shadow-Cursed Lands, and finally out towards the city, the team at Larian exploit the boundaries of each area to elevate your adventure. When you move from the almost bucolic scenery of act one into the soul-sapping darkness of act two, Farhang Namdar explains this contrast offers “the feeling of story progression,” and it’s a trick Larian uses repeatedly.

While the wilderness has fights sprinkled like glitter alongside scintillating conversation, and the Shadow-Cursed Lands see you scurrying between bright spots, the final act’s city was designed more in the vein of “a classic dungeon grinder with house-to-house navigation, lots of cellars, underground areas, [and so on].”

“We wanted to give every act its own personal flavour. We wanted to start out familiar but with a clear goal for the player,” Namdar begins, going on to say, “So act one was more of a classic RPG start with a clear objective: the player is exploring the wilderness while trying to extract the tadpole in their head. Act two restricted the player’s movement through the Shadow-Cursed lands, which created a completely different dynamic allowing the player to meet the forces of darkness and those who rebel against them. Act three brightened up the playthrough and introduced city gameplay.”

Designing the world of Genshin Impact

It’s far from the only game in which the environment so directly reflects your protagonist’s narrative journey. Live service title Genshin Impact (one of the best free PS5 games) features the massive setting of Teyvat, a world that’s been expanded through frequent updates, some of which have introduced totally new regions to lose yourself in. The latest of these is Fontaine, a water-logged land described as a ‘terrestrial sea.’ In terms of scale as much as anything else, it’s a far cry from where the Traveler’s journey begins.

We chatted to the internal team responsible for Genshin Impact (one of best anime games you can play) at developer HoYoverse, and they offered answers collectively over email. “The areas that have already been released carry the Travelers’ experiences in specific phases of their journey,” the team tell us. “As a result, the way they’ve been designed also differs. For example, content density in [the starting city of] Mondstadt is relatively low.”

This was in part for practicality’s sake, they say, “One reason is the limited technology and experience we had during the early development of Genshin Impact,” before adding, “In the meantime, because Mondstadt is the first area players can explore, we also hope to start easy and evolve step-by-step.”

Teyvat is a land dominated by the will of the seven Archons (essentially gods), and the differing ideals they hold dear. Mondstadt’s Archon is known by a few names, including the God Of Freedom. As a result, this Archon does not rule directly over Mondstadt, instead preferring to play music and sip dandelion wine, enabling the city’s people to forge their own fates; it’s a fitting first step into this expansive live service game. Teyvat’s second region offers a direct thematic contrast, as the land of Liyue is ruled over by an Archon known as the God Of Contracts.

To put it another way, the Traveler has gone from being a stranger in a strange land with a horizon of opportunity ahead to forging bonds that give them a reason to stay – or at least keep them and you, the player, coming back.

Going retro with Parcel Corps

Movement mechanics are another essential part of the bigger world-shaping picture, so let’s shift gears. We spoke to William Barr, the director of Billy Goat Entertainment, about the studio’s wheelie exciting upcoming project, Parcel Corps. This new retro-inspired indie game mixes Jet Set Radio and Crazy Taxi (one of the best upcoming game remakes) but with bicycle couriers trying to outpace the demands of the gig economy with nothing but two wheels and their wits.

Central setting New Island is a place you can cycle across from end to end, but isn’t an ‘open world’ in the traditional sense. “It is level-based. Each zone in the city forms its own self-contained level, but if you want to travel all the way around the map you can. We usually have a small bridge or tunnel that informs you that you’re entering a new zone,” Barr explains, before quipping, “We’re old skool!”

New Island is literally not a level playing field; your cycling courier can grind rails, defy gravity by launching themself off ramps, or glide across walls like they’re straight out of Tokyo-to.

“We took inspiration from our own, personal commutes. Nothing is as frustrating as getting caught in traffic. Often, the best thing to do is ride along the side of a bus, jump onto some scaffolding, then grind along some railings while pedestrians throw themselves out of your way,” Barr jokes. “Some of that is exaggerated – in real life the pedestrians don’t always manage to move quickly enough.”

Parcel Corps refracts modern-day mundanity through a funhouse mirror. Barr says the team were going for a “Transatlantic-type vibe” for New Island. “Being based in the UK, we are most familiar with cities and architecture over here,” Barr admits, “but the weather here sucks, and the ‘blue skies, ’90s arcade’ aesthetic has more of an American, West Coast feel. So we kind of merge those two aesthetics together.”

The people who populate New Island are larger-than-life, and humour is baked into the world design. When we ask Barr about this, he quips, “I presume you’re referring to all the signage with naughty names?” He goes on to add, “We also like to indulge in a bit of the ol’ ‘environmental storytelling’ that level designers love – for example, [discovering] the offices of Billy Goat Entertainment with an eviction letter stapled to the door.” He continues, jovially, “A sign of things to come, no doubt, art imitating life.

“But back to the naughty names – all I’ll say is that the depravity of some of our more mild-mannered team members continues to shock me,” Barr jokes. “In fairness, most of this stuff flies over my head. I lead a very sheltered existence, but this project has definitely been an education.”

Proving his point, Barr then shares that when it comes to level design, “We do love a good weenie.”

Let’s scoop our minds out of the gutter: ‘weenie’ is a term that originates in theme park design, describing a point of visual interest (think the Disney parks’ central castle) that draws visitors towards it – it’s not filthy, it’s magical. Barr explains, “Trying to ensure that there are good sight lines so you can catch a glimpse or two of a large weenie (for example, cranes in a construction yard) really does help.”

Challenges of open world design

Ensuring players find their way through a non-linear space is no easy design feat – and Larian Studios signed up for one hell of a challenge.

“I remember the day Swen [Vincke, Larian’s CEO] told me that our next project was BG3. I literally went from joy to anxiety in a couple of seconds,” Namdar shares. “We had joked about this frequently back in the days, so in many ways it was a dream come true. It was a great honour and a lot of pressure to develop the next instalment of this groundbreaking franchise. We just knew we had to make something unique to fulfil our commitment to the fans, [though] it wasn’t easy following up on what is widely regarded as one of the greatest RPGs of all time.”

Besides all of that, Namdar stresses, “Building good RPG cities is extremely difficult.” He describes all the plates Larian has to keep spinning, saying, “We have to account for the gameplay composition. The cadence at which you encounter things. When and where you experience combat. At what point you talk and if the backdrop is incredible enough for the cinematic dialogue. How long you walk before you reach another dead end. How we light areas to make sure the corner of your eye catches a point of interest that can get you out of that dead end. The spaces we create and objects we place to convey the story and communicate the important narrative beats – all of the above while keeping an eye on how the game performs on various platforms.”

Namdar delves into the main city’s central design challenge: “You always have to deal with the density of events and navigation. Players, including myself, always get lost in cities. You need a natural way for players to orient themselves in a dense environment.”

We’re glad to know it’s not just us taking wrong turns in the lower city. Though in such a dense space, losing your way can be an asset – would we have found the zombie camping out on the beach or stumbled upon the hag victims’ support group without poking around? Or (Namdar’s favourite) the Festering Cove?

We knew that we had to build the city on a slope so the player could always pan the camera down to the shoreline and up to the city wall for orientation

Farhang Namdar, world building director, Larian Studios

“Feeling lost is part of the gameplay,” he agrees, “[But] it becomes frustrating when you feel lost all the time.” To help better situate players, Baldur’s Gate takes inspiration from the historical cities throughout the Mediterranean, many situated close to the sea.

“We knew that we had to build the city on a slope so the player could always pan the camera down to the shoreline and up to the city wall for orientation,” Namdar explains. “Heading into the city meant the water was always on your left, while heading back meant the water was on your right. Climbing up meant you were heading towards the city walls, climbing down was the shoreline.”

Building history into a world

In addition to top-level wayfinding landmarks, BG3 is full of smaller signposts – metaphorically and literally. Larian tries to “frequently remind [players] of the [act’s] narrative beats” through environmental touches such as how an area is decorated, along with ambient and direct conversations with NPCs that “reflect the state of the story.”

For CD Projekt Red’s Krzysztof Kornatka, solid world building extends far beyond the critical path; he tells us it’s all about allowing the player to understand “the world, its history, relationships, and intrigues simply by observing the environment.”

He goes on to say, “Whenever I can, I add something that emphasises the character of a particular place. Sometimes these are small things – for instance, the traces of a crime at a subway entrance right next to a police station show that the NCPD has little to say in the area.”

But world building is more than tiny details. Kornatka starts, “While working on the Arasaka area, one of the directors asked for something to commemorate the explosion of the main Arasaka headquarters in 2023.” Drawing inspiration from the film Demolition Man, Kornatka created the Arasaka Memorial, a massive space preserving part of the original lobby along with some of the street nearby, museum-style.

We’ll skirt spoilers and say it makes sense to go big on an event in the city’s past that ultimately sets much of Cyberpunk 2077’s plot in motion, but Kornatka then shares, “I found out that they originally just expected a commemorative plaque somewhere on the side of the building. What can I say? In [CD Projekt Red’s] City Team, we like to utilise larger spaces!”

World building is one way to signpost things, though sometimes ensuring players don’t feel lost or overwhelmed is a matter of pacing. “Whenever the player starts to feel frustrated, the possibility to reach an elevated location happens to [be nearby],” Farhang Namdar slyly remarks.

Developing an open world

It’s all a balancing act – one that can be completely undone by your own map. Genshin Impact expands into new regions at least once a year, with long-established areas like Liyue sometimes receiving tweaks too through updates. For instance, new subregion Chenyu Vale now connects Liyue to Fontaine by water. But with each additional region bigger and more ambitious than the last, the original maps didn’t really – ahem – cover it any more.

The team share, “The old maps could no longer precisely display the terrain and allow players to easily locate Teleport Waypoints. […] As a result, when we launched Fontaine and its underwater areas last year, we added the Multi-Layered Map feature. This feature was also applied to areas that had already been released.”

But how often have we delved into an open world only to let most of it pass us by as we beeline to the next waypoint? It’s a struggle CD Projekt Red’s Krzysztof Kornatka knows all too well. “You can always follow [Cyberpunk 2077’s] GPS if you want to reach your destination as quickly as possible,” Kornatka begins, “but if you prefer to embody the role of a netrunner or sniper, it’s worth exploring the area thoroughly. You might find a passage to a higher level from where you can better assess the situation or quickly escape to a nearby parking lot where the good old Quadra you parked earlier is waiting for you. During the design of the entire map, player freedom in movement was very important to us.”

Combat both scars and shapes Night City. “When firearm combat comes into play, the environmental design undergoes a total transformation,” says Kornatka, “We [on Cyberpunk 2077] need to provide places for both the player and enemies to take cover from gunfire. Conversely, in melee combat scenarios, it’s quite the opposite. Having all manner of cover becomes rather annoying for the player, as they have to contend with obstacles in the environment that hinder deadly acrobatics or swift evasions from strikes.”

Kornatka goes on to say, “At the very beginning, the player doesn’t have access to the entire map. Of course, this is explained narratively and supported visually. This allows them to gradually explore and get to know the character of Night City. Naturally, the GPS system comes in handy, but as an environment artist I always strive to create standout landmarks, often with specific characteristics for each region, allowing the player to recognise where they are without consulting the map.”

Spotting landmarks in dense, urban environments can be tricky, so the team deployed a number of other subtle signposts. For instance, each of Night City’s six districts has its own personality, expressed through “its own architectural style, lighting colour, and dominant hue.” Graffiti also clues you in, as each gang’s influence on its home turf is represented visually, daubed all over the walls.

Ensuring players don't get lost

The cartoony visuals of Parcel Corps prove essential to finding your way. “When the game was at the white box stage, it was much more difficult to learn a zone,” William Barr shares. “However, when the art got added it became so much easier.”

He continues, “Much to the dismay of our environment artists, we didn’t go down the whole [procedurally] generated route when it came to the environment. Largely this was because you can ride on pretty much every surface in the game, thus necessitating a bit more TLC for our concrete boxes, which ensures they have a unique, hand-crafted look, aiding the player in remembering them.”

The team at Billy Goat Entertainment approach crafting cycle paths in several ways. “Some of the team find it helpful to have a theme, or a key piece of architecture that they’ll then plan routes around. Others prefer just to whitebox something that they think is fun. It all then gets iterated over,” Barr explains.

There’s nothing stopping players from mixing and matching routes either. Barr adds, “When we drop missions in, people typically find their own way around – maybe they only use part of one of these planned routes but then do something unplanned for the rest. If a route seems cool, we then try and accommodate it in another design pass.”

Finding your own way through Dying Light 2 makes traversal in that game compelling too. One of the key challenges of building Villedor was creating an environment that would be fun for anyone to get around. Tymon Smektała reflects, “This means that we had to make it accessible to newcomers (and please bear in mind that parkour, especially in [first-person perspective], is actually quite a difficult gameplay mechanic to grasp), but at the same time make it so people that are willing to engage with it and learn it could feel that their abilities increase with time.”

The team have worked to build environments that offer players plenty of opportunity to “connect their [parkour] moves in an interesting way”, with much of the fun of spaces like this or Parcel Corp’s colourful New Island being the simulation of a physicality that can be tricky to imitate in real life.

Genshin Impact sees you sprint, climb, swim, and glide all over incredible vistas. The team sum up the appeal beautifully: “Teyvat is a fantasy world, and we hope actions done by players are better rewarded here than in the real world.”

Encouraging exploration

From unlockable shortcuts to the speed-boosting trick system, Parcel Corps offers a space that is intended to feel “fun to just potter about [in].” But with so many options for making your own way, how do you encourage players to shun the path of least resistance? Well, New Island doesn’t just pave the way for bikes – your courier can be corralled by coppers or sent flying by careless cars.

“We try to encourage the player to avoid the roads where possible. We have to include roads that somewhat make sense to make the city seem believable, but just following them can be quite dull,” Barr admits. “So, to discourage that, one thing we do is carve alleys and suggest other shortcuts to get you off there and also, yeah, make the cars a little unforgiving. Not unlike real life I should add – I mean, I’ve been hit by a couple of cars while on my bike in real life, and it was never terribly pleasant.”

Tension is the lifeblood of so many virtual environments. For instance, Dying Light 2’s zombies make sure you maintain your momentum across the city. “[The presence of the Infected] actually impacted [the design of Villedor] a lot, especially in areas like visibility range or how tight the playable areas are,” Tymon Smektała explains. “We want players to be surprised by zombies that they notice at the very last moment, we want them to feel that the threat those zombies pose is basically at the reach of their hands. We used a lot of tricks there but I don’t want to uncover all of our secrets…”

The danger of missing the jump is always there, though falling to your death over and over arguably isn’t ‘fun’. Smektała says, “So if the jump is – for example – two metres, then we have gaps that are 1.8 [metres] in range, to leave players some room for error.”

Often, you’re surviving by a hair’s breadth but nonetheless, you are still surviving. “For many players, Dying Light became this total zombie experience […] where they can jump in at any minute, spend some time in the locations that we’ve built, having fun surviving,” Smektała tells us. He also shares, “Sometimes [the] fun is really mindless and you just run around checking if you can kill all of the zombies in sight, but usually it’s more grounded, more serious, more tense [survival].”

The result is a ‘zombie playground’ that keeps players coming back, and that’s the real secret ingredient, the real mark of success for any videogame setting or immersive world – the return of the player. After all, without you hitting t, without you deciding it’s a place worth fighting for, the world ceases to be. Maybe with that same passion, we can save our real world from its own apocalypse.

This feature originally appeared in Play Magazine issue 40. If you want to read more content like this subscribe at Magazines Direct. If you've been inspired by the history of open world game design on PlayStation, then get creating with the best laptops for game development and the best drawing tablets.

Jess is hardware writer for PC Gamer. She is the former games editor of PLAY Magazine as well as previous writer for Official PlayStation Magazine, and is known for championing the weird, the wonderful and the downright janky.