Brain scans sound like a terrifying way to resolve logo disputes

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Five times a week

CreativeBloq

Your daily dose of creative inspiration: unmissable art, design and tech news, reviews, expert commentary and buying advice.

Once a week

By Design

The design newsletter from Creative Bloq, bringing you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of graphic design, branding, typography and more.

Once a week

State of the Art

Our digital art newsletter is your go-to source for the latest news, trends, and inspiration from the worlds of art, illustration, 3D modelling, game design, animation, and beyond.

Seasonal (around events)

Brand Impact Awards

Make an impression. Sign up to learn more about this prestigious award scheme, which celebrates the best of branding.

Sadly, logo design can sometimes turn ugly. Here at Creative Bloq, we fairly regularly report on the battles that can arise over similar-looking logos (many of them involving Kanye West). Sometimes things go as far as to reach court.

When that happens, the usual argument put forward by the plaintiff is that the offending logo could confuse a "reasonable consumer." But how do we really know what this hypothetical rational customer thinks? To be sure, the judges would need to read their minds.... and it seems it might just come to that (take a look at our piece on similar logos to see how easy it is to inadvertently replicate a design).

We've seen a bunch of logo and branding trademark disputes recently. Lidl vs Tesco, Kanye West vs everyone, the watch giant Rolex against... erm, an unknown children's clock company. In most cases, the argument is the same: the consumer will be confused. But how can we really tell if a right-minded person would confuse a cheap cartoonish children's clock with a $6,000 Swiss watch? Well, how about we scan their brains?

That's the rather dystopian proposal put forward by former Berkeley Haas postdoctoral researcher Zhihao Zhang and a team at the Darden School of Business, University of Virginia in a paper in Science Advances. They reckon that brains scans would be an objective way to find out whether people see a likeness in two logos.

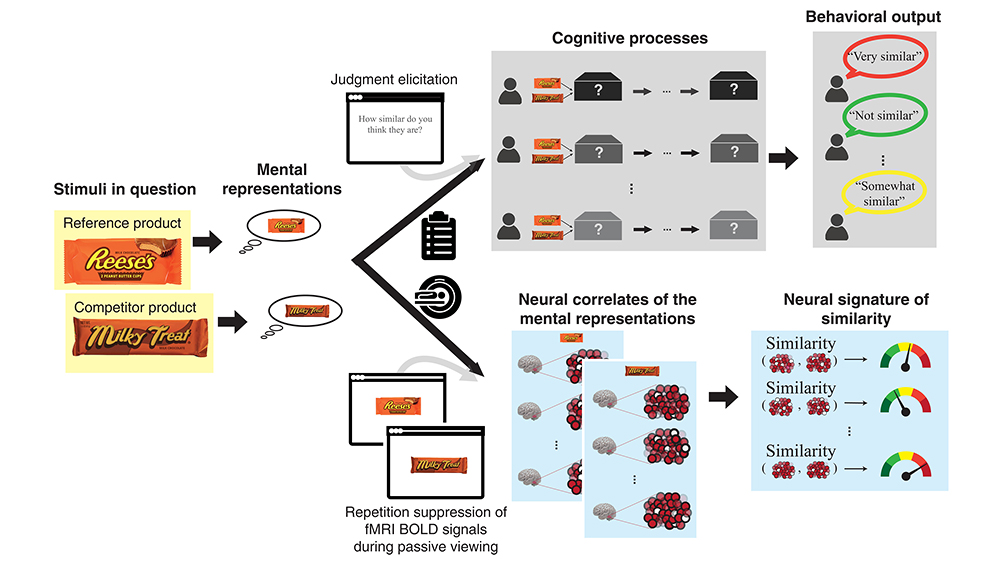

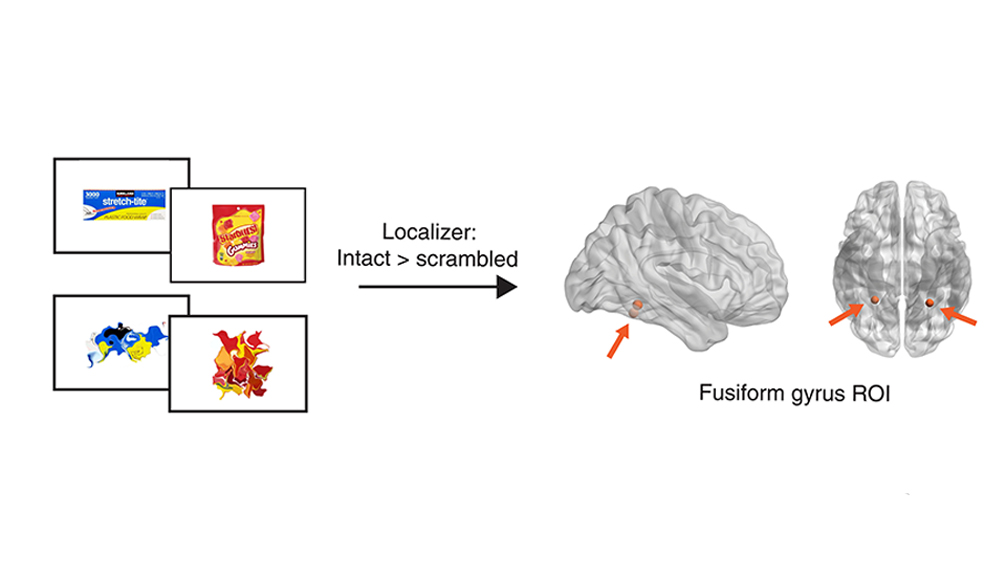

Previous research shows that the brain supresses activity when it sees an image similar to one it has seen before. So the team's solution is to establish similarity in logos using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) together with a technique called repetition suppression (RS).

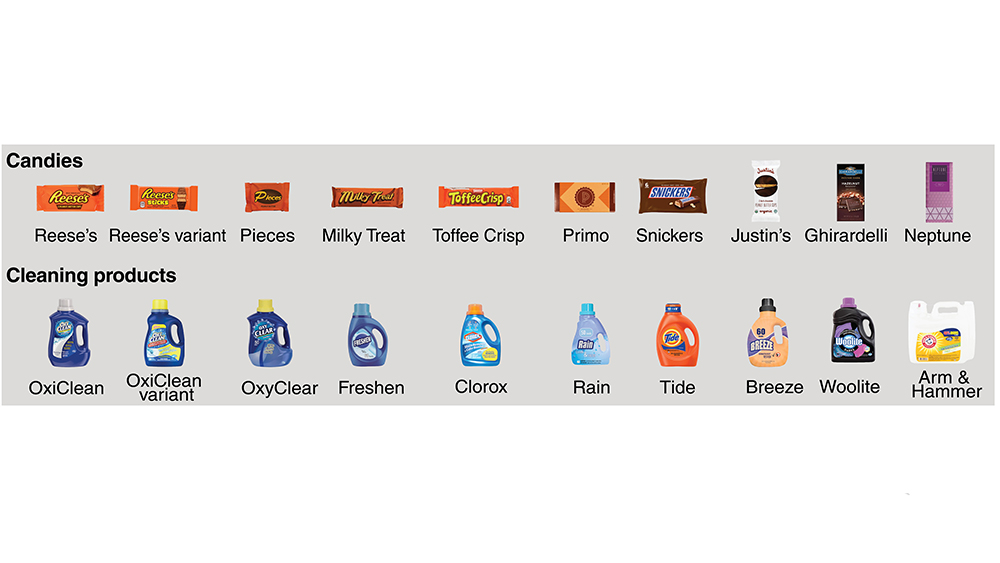

To test the theory, they put test subjects in fMRI scanners and showed them pictures of brands and hypothetical copycats. It claims the process would cost little more expensive than the current procedure of carrying out surveys and would avoid the problem of leading questions. They say it could also be used for other copyright issues, for example in testing if a song has copied another piece of music.

Zhang says: "Similarity is an incredibly hard thing to measure in an objective way. Making things worse, in the adversarial legal system, two opposing parties each hire their own attorneys and expert witnesses who present their own evidence.”

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

To illustrate the challenges, Zhang holds up the example of a dispute between the well-known toothpaste brand Colgate losing a challenge against Colddate because the judge decided the branding was not “substantially indistinguishable.” (We were also amused last year when Gucci lost a case against CUGGL in Japan.

There are some limits though to the proposal, though. The method can't decide how similar is too similar. Dr Team member Andrew Kayser from UC San Francisco says that would still be up to a judge to decide. It seems there will still be an element of subjectivity in the decision.

Read more:

Joe is a regular freelance journalist and editor at Creative Bloq. He writes news, features and buying guides and keeps track of the best equipment and software for creatives, from video editing programs to monitors and accessories. A veteran news writer and photographer, he now works as a project manager at the London and Buenos Aires-based design, production and branding agency Hermana Creatives. There he manages a team of designers, photographers and video editors who specialise in producing visual content and design assets for the hospitality sector. He also dances Argentine tango.