Behind the scenes on the art of Assassins Creed Origins

Assassin's Creed's art director explains how he wants to take you to a virtual world where danger feels very real.

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Watch a film and you're an observer. But play a game and you're a participant. For Raphael Lacoste, art director of Ubisoft's hugely popular Assassin's Creed franchise, this is an important distinction. Growing up in the 80s, Raphael played games like Pitfall, Another World and Rick Dangerous, a platformer inspired by Indiana Jones. But even then, Raphael looked past point-scoring, beating the boss and completing the levels. He was interested in the story.

"It's funny to remember that visual quality at this time wasn't a big issue," the Frenchman says, "because our imagination was taking over. The rendering was really abstract, but the experience was still immersive."

Later on, Tomb Raider – the boss level in particular – scared him. Playing Omikron: The Nomad Soul and Abe's Oddysee changed something in the young man. Again, he felt "immersed in the game experience."

Raphael says: "If you watch a movie then you're moved and transported by the characters and their story – you enter their world – but for the most part you receive information. You're just a spectator. In contrast, playing games makes you more proactive and gives you that feeling that you're playing your own story.

"If you're putting yourself in danger, you can feel this stress. You escape, hide and find your own strategy. What I love the most is to be able to freely explore an immersive world, through the vector of the hero that you occupy. Video games can literally take you into another dimension."

Why recreate reality?

At school, Raphael was never much of a student. "Instructions were never, and still aren't, part of my priorities." He preferred to stare out of the window, wander about outside, or draw. Yet even then, he wasn't interested in copying the world around him. Instead, he wanted to create brand new worlds.

"Why recreate reality? It surrounds us. It's sometimes beautiful, sometimes disturbing. Reality can drive us to feel complex emotions and have deep thoughts. But I love to reconstruct reality in order to create new environments that push us to wonder, and allow us to escape.

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

"I like to blend cultures and landscapes, often exotic ones, to create something new, something different. What could an Icelandic landscape combined with the architecture of the ancient city of Petra look like? Or imaginary castles that defy gravity on a background of exaggerated Norwegian mountain peaks? My objective is to create fantastic worlds of what could have been."

Creative upbringing

Raphael studied at Bordeaux's School of Fine Arts and Decorative Arts, and worked as a photographer and set designer at a theatre company. He enjoyed the work, but it didn't pay much. In 1997, his dad – who also played games with Raphael and taught him photography – bought him a computer. He learned 3ds Max, created his first demo piece, and built up a portfolio. He received a diploma from what's now called the ENJMIN Institute of Game Design, then secured a job as an environment designer at Kalisto Entertainment,.

Kalisto went bankrupt in 2002, but then Ubisoft called and Raphael took the company up on its offer. He moved to Montreal, Canada and became an art director at the games publisher. Raphael now works as the brand art director on the Assassin's Creed franchise. In October 2017 Ubisoft released the tenth instalment of the game, Assassin's Creed Origins.

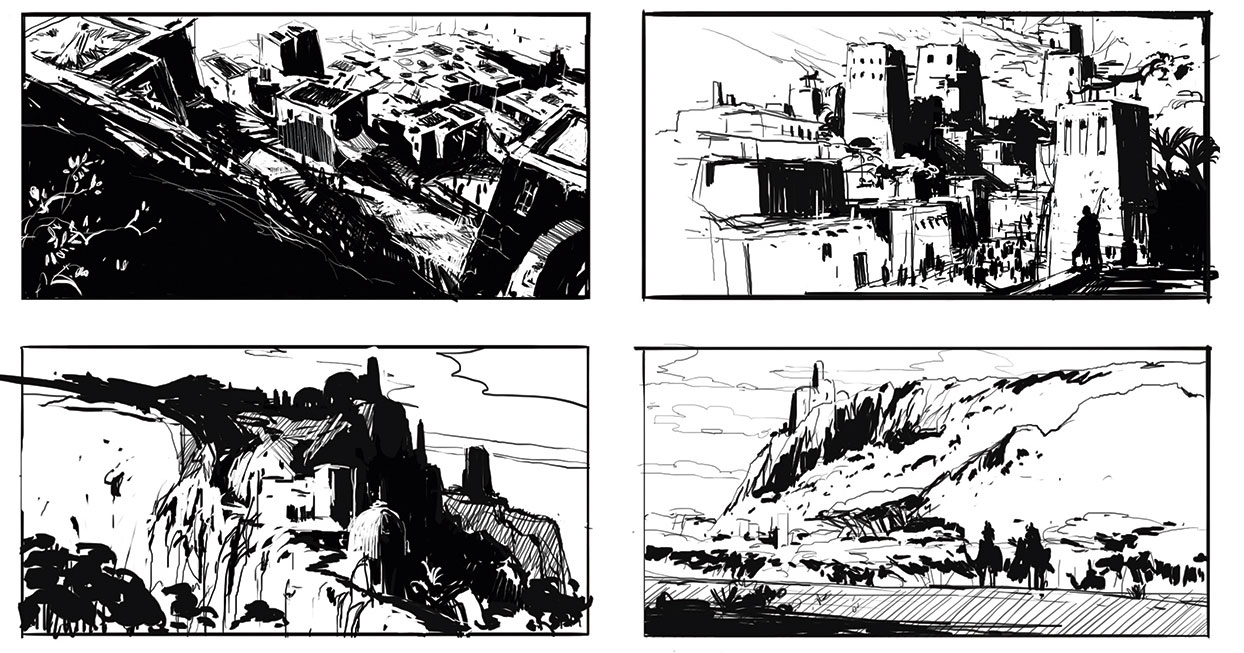

Raphael's job changes as a game goes through its many development stages. At first, he and the team focus on research, doing their "homework": lots of concept art, sketching, drawing and painting. "It's the most creative time, artistically," says Raphael, "and also a quiet period."

The team explores specific time periods and locations. They try to find "an interesting pivotal moment of history." It has to be something exciting, with a bit of mystery to it, an "inspirational playground" for both player and developer.

Once that's in place, they define some set pieces, work up illustrations to "sell" the chosen world and characters, and then start thinking about a hero. These first month are full of creative freedom. Anything could happen. The game could go anywhere. Raphael finds the blank page both stressful and thrilling. He's happy to try things, let them fail, then begin again. But at some point, the game must become something real. They need have a setting, artwork and gameplay prototype in place to sell the idea to headquarters.

The team throws in the overall game and level design with story and art to make the first playable version of the game. "This is where fights can happen," Raphael says. "It's both a challenging and crucial period. I spend more time in meetings than working with the illustrators."

Now Raphael goes from team to team and makes sure that the "original benchmarks and visual standard" are followed throughout. To join his team, you need a good mix of skills: "They need to have interest in the game and have excellent skills in environment design and composition, but also storytelling. Our levels are complex to create as they blend historical context, fantasy, gameplay interactivity, and need to be epic and memorable."

Departing – and returning

In February 2007, Raphael finished work on the first Assassin's Creed and decided to leave the game's industry. "I felt that I needed new challenges," he says, "I wanted to learn new things."

He went to work at visual effects firm Rodeo FX, a small company at that time, creating matte paintings and concept art for Death Race, Terminator Salvation, and Journey to the Center of the Earth.

"The film industry is older than the video game industry," says Raphael. "I learned a lot at Rodeo, like mastering image composition, rendering, technical skills in Photoshop and even working in 3D software. I still use what I learned there now. But I felt that my job as a matte painter for film was a little too technical, less creative."

You watch a movie, but you play a game: "So I decided to come back."

This article was originally published in issue 157 of ImagineFX, the world's best-selling magazine for digital artists. Buy issue 157 or subscribe to ImagineFX here.

Related articles:

Gary Evans is a freelance journalist and travel writer. He is a former staff writer for Creative Bloq, ImagineFX, 3D World, and other Future Plc titles.