Why industry mentoring is utterly invaluable

The web is a young industry, built on community and helping others. Craig Grannell explores why mentoring benefits us all.

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Five times a week

CreativeBloq

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Once a week

By Design

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Once a week

State of the Art

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Seasonal (around events)

Brand Impact Awards

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Community has been fundamental to the web industry since the beginning, forming a culture of sharing information and expertise. Now that same community spirit is helping to shape the industry's future, as a new wave of internship and mentoring schemes give the original generation of web professionals a chance to pass on its knowledge to the next.

"A lot of people are self-taught - we're of that generation," says Code Club co-founder Clare Sutcliffe. She trained in print design, but switched to digital and has had various mentors. Now, via Code Club, a nationwide network of after-school groups, she mentors the next generation of coders: "There's a sense of giving back when you're well-versed enough. That cyclical effect is a reason the industry's worked so well."

Teaching the next generation

"Learning from someone who's doing what you're trying to do is invaluable," Sutcliffe points out. "That's why Code Club works. Our volunteers are in schools, being role models and helping them learn by supporting them."

And once the volunteers have initiated the process, mentoring begins to happen on other levels. "Kids that fly ahead help those going at normal pace," adds Sutcliffe. "Volunteers become mentors, supporting each other!"

But while kids soon adjust to the new way of learning, adults can take longer. Sutcliffe says there is a residual fear of training your own replacements. "We've had people say, 'If we teach the kids, they'll take our jobs.' They're nine! It's unlikely to happen immediately. Anyway, if you're thinking that you don't want to mentor someone because they may be better than you, perhaps you've got other problems to address!"

It could be argued that the need for organisations like Code Club highlights a failure of traditional education. Greg Hoy, president of US user experience and design consultancy Happy Cog, disagrees, pointing out that colleges are "[just] designed to teach the mechanics". Only when immersed in the industry can you see how the business of design really works.

However, there is a Catch-22 common to all industries: newcomers lack the experience to get a job, but experience comes from having a job. Mentoring - in the form of company internships - can provide that much-needed experience. Internship schemes may be more familiar to those working within the industry than initiatives like Code Club, but they require an equal amount of commitment and effort on the part of the mentors.

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Hoy recalls sadly that Happy Cog's first intern "languished, because we didn't have time to give her meaningful things to work on - it was only on her own behalf that she pursued learning opportunities".

We are always looking for ways to convert interns into full-time employees

Now a larger organisation, Happy Cog can accommodate interns fully, and it scrutinises them during interviews just as it would anyone else joining the team. "We want to feel good about them wanting to learn from us and are always looking for ways to convert interns into full-time employees," says Hoy. "We're willing to invest the time and effort to make that happen."

A two-way relationship

According to Happy Cog founder Jeffrey Zeldman, internships help young designer and developers avoid serious career mistakes, "[saving] themselves years of grief of getting trapped in the wrong place".

Like Hoy, Zeldman warns both parties must approach things in the right way: "The company must be big enough [to] spend time training interns, and they have to pay something. The intern must recognise it's no good if they end up somewhere where they mess about on Facebook all day."

Happy Cog's own internships are informed by prior experiences. Zeldman recalls an early copywriting job where he got fired by a clueless boss who didn't mentor him and paid little. "It just seems unfair to grind somebody up and spit them out cheap," he says. "Too many agencies feel an obligation to have a certain number of interns. It's just wrong. If you're going to invest the time, it benefits you to keep people on. If you don't have the time, resources or willingness to work with people, don't provide an apprenticeship."

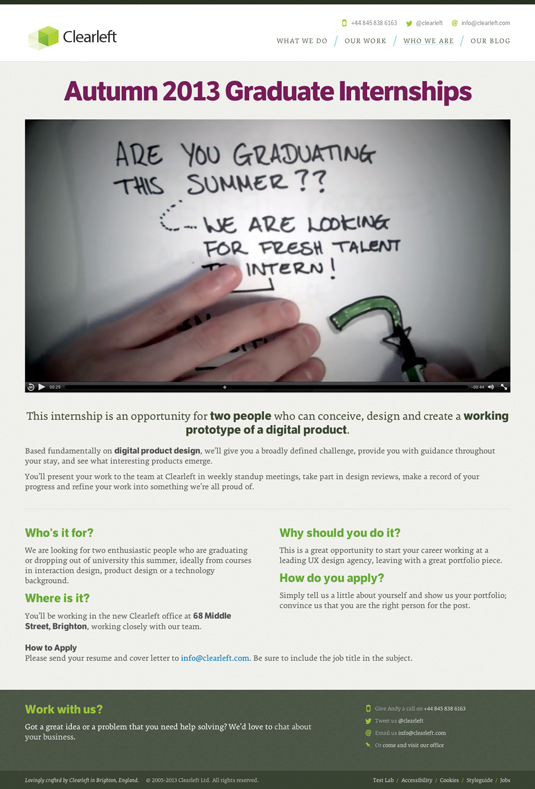

On the opposite side of the Atlantic, British UX and web design agency Clearleft also regularly takes on interns. CEO Andy Budd says that the practice comes from the company's deep culture of mentoring: "I started a skill-swap network in Brighton about 10 years ago, and a lot of Clearleft's DNA is built on sharing, through blogs, talks and workshops."

While Budd still believes that workshops are "great at getting people interested", he noticed it was becoming harder for graduates to get a job at an agency like Clearleft. "You learn through on-the-job practice, so we decided to narrow our focus and deal with individuals through internships," he says.

Like Happy Cog, Clearleft pays its interns. Although, as a smaller company, it finds it harder to offer them full-time positions at the end of internships, it fosters their careers in other ways. "After three months of working on internal projects and sometimes client work, we often recommend our interns to other companies," says Budd. "It's amazing to see how people can progress in their time with us."

One beneficiary of the internship scheme is Josh Emerson, now frontend developer at zeebox. Emerson says his time at Clearleft enabled him to understand the 'why' of taking certain approaches: experience he thinks is unlikely he could have gained in any other way.

Although taking on interns rarely helps a company financially, Budd says that the relationship is still mutually beneficial: "They are fresh blood and bring in new ideas. You can live vicariously through their experience, and feel good about being part of their future. That feeling is immeasurable."

Ethical responsibility

Like Zeldman, Budd is disgusted by companies that "see interns as cheap labour, for doing things no one else wants to do". He says that any agency considering taking on an intern "should not see them as a resource to exploit" and "owes them a duty to make the internship matter, because they might only do one in their lifetime".

Although Budd says that mentoring isn't a duty, he strongly believes that it's "up to those who've got ahead to help those on the way up".

"Most senior industry figures I know learned everything off the web, through the kindness of strangers sharing knowledge and expertise," he adds.

Most senior industry figures I know learned everything off the web, through the kindness of strangers

Budd suggests that those wanting to teach simply "allocate an hour or two per week to talk to people or local schools". He also hopes that the industry as a whole will become more appreciative of such work, noting that he has seen "a lot of nastiness and back-biting of late against people who put in a lot of community effort".

Going solo

Some enterprising solo developers are also working to provide apprenticeships. Freelance designer Laura Kalbag decided to mentor a small team after receiving regular emails asking for advice about getting into freelancing and client work, combined with client proposals that had low budgets attached.

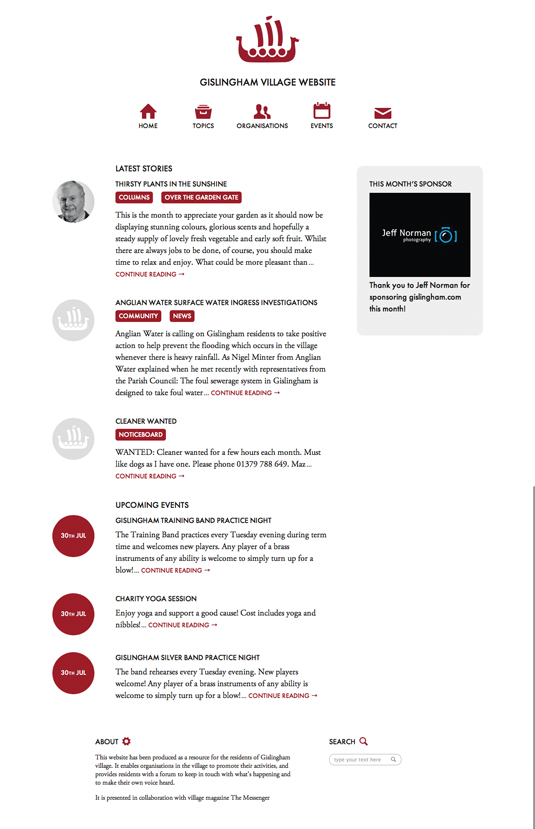

She figured the more worthy clients (such as charities and community sites, rather than those just wanting a site on the cheap) could be ideal for newcomers to tackle, if guided by a mentor. Over four months, Kalbag helped a trio of designers create the Gislingham Village website. The process is outlined on Kalbag's blog.

Although the site was a success, Kalbag says a one-to-many mentoring approach isn't really feasible when working on live projects. "There were big challenges regarding communication, getting to know each other's skills, and the team needing skills it didn't necessarily have. I underestimated how much time I'd have to invest, and I think having the team shouldering the project was way too much."

Kalbag suggests solo industry figures follow the example of frontend developer Ryan Taylor in offering one-to-one mentoring, supporting the mentor's own projects, and is planning something similar in future.

However, she found the experience of working on the Gislingham Village website valuable: "I was asked why I did things in a certain way, and that made me question my process. This helped me understand why I do things I do and areas where I could do things better. It also reinforced my belief that teaching relationships work better face-to-face, because of the in-depth interactions you need. It's hard to get away with doing everything remotely."

Remote mentoring

Nonetheless, there have been successful cases of remote mentoring. Freelance frontend developer Anna Debenham instigated an online skills-swap network two years ago to match people who wanted to teach with those who wanted to learn. "It was a spreadsheet, really. Very simple. I just printed it out, pinned it on the wall, sent some emails and got people talking," she explains

According to Debenham, encouraging people to adopt a relaxed schedule is beneficial when communicating remotely: "They checked in 'whenever'. It became a form of encouragement rather than people teaching specific skills. But that's what mentoring often is - a support network. It doesn't have to be about skills, but motivation."

Mentoring often is a support network. It doesn't have to be about skills, but motivation

Interestingly, more people were interested in helping than asking for help: something that Debenham believes may be due simply to potential participants being unaware that help was available.

Getting the word out

If Debenham's experiences are typical, the main thing holding back the growth of mentoring schemes may not be a lack of demand, but simply a lack of awareness that such schemes exist.

"Not enough people in our industry are taking advantage of mentoring," she says. "Freelancers are often isolated, working alone, and not learning new skills easily. The best way to learn is to work with someone, but if you don't have the opportunity, that can be hard."

Ultimately, Debenham believes everyone in the industry should both teach and learn. "It would be amazing if everyone got involved somehow," she says. "It's great to teach and offer moral support, and it's also good and healthy to admit you don't have certain skills - and would like them."

After all, as Debenham points out, the benefit of mentoring is both simple and universal. "Mentoring is just about guiding people so they don't make every mistake you made," she says. "It's giving and receiving a push in the right direction."

This article originally appeared in net magazine issue 247.

Liked this? Read these!

- Our favourite web fonts - and they don't cost a penny

- Brilliant Wordpress tutorial selection

- The designer's guide to working from home

The Creative Bloq team is made up of a group of art and design enthusiasts, and has changed and evolved since Creative Bloq began back in 2012. The current website team consists of eight full-time members of staff: Editor Georgia Coggan, Deputy Editor Rosie Hilder, Ecommerce Editor Beren Neale, Senior News Editor Daniel Piper, Editor, Digital Art and 3D Ian Dean, Tech Reviews Editor Erlingur Einarsson, Ecommerce Writer Beth Nicholls and Staff Writer Natalie Fear, as well as a roster of freelancers from around the world. The ImagineFX magazine team also pitch in, ensuring that content from leading digital art publication ImagineFX is represented on Creative Bloq.