The secrets of 3D scanning

How real actors are turned into movie production-ready CG models using 3D scanning tech.

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Five times a week

CreativeBloq

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Once a week

By Design

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Once a week

State of the Art

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Seasonal (around events)

Brand Impact Awards

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Whenever you see a comic book hero flying through space or crashing through a wall, chances are they're a digital double of a real actor expertly crafted by a visual effects studio.

But how is an actor's likeness captured with such absolute photorealism? These days that's often the domain of 3D scanning providers, which rely on portable – and often custom – photogrammetry rigs that they can bring right onto the set. That way they can whisk actors in and out of the scanning process and generate a CG model of their face and body as fast as possible, helping to save the film studio a lot of expensive production time.

One company in the 3D scanning services fold is Pixel Light Effects, based in Vancouver, Canada. Using its mobile photogrammetry setup, the studio recently scanned principal actors and extras on location in British Columbia for Matt Reeves' War for the Planet of the Apes, creating detailed CG models to give to Weta Digital for the subsequent digital double work.

We asked Pixel Light Effects, which also has a presence in Beijing, how it tackles a typical actor photogrammetry scan – from the capture process right through to producing a useable high-resolution CG model.

The basis of a 3D actor scan

Over the years, several methods have been used to accurately capture the essence of an actor in CG. These include laser scans, specialised 'light stage' contraptions, and now most commonly, photogrammetry. This process essentially involves taking hundreds of photographs of the actor from multiple angles. The photos are fed into computer software, which then sets about comparing the images and using them to build a 3D model.

Photogrammetry is considered an efficient method of capture because it is quick, especially in a camera rig that has many cameras at many angles taking all the pictures at the same time.

Indeed, that's what Pixel Light Effects uses, and further mobilises the scan by having it take place in the back of a truck that has the photogrammetry rig permanently installed inside. The truck can be driven directly to the set where the actors are, or to just about any other location.

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

"Mobility is the biggest issue with a rig consisting of hundreds of cameras," says Pixel Light Effects' CEO, Jingyi Zhang. "Taking them apart and putting them back together is very time-consuming and labour intensive. It just doesn't feel right. However, due to the tight schedule of the production, sometimes it's just impossible to have the talent come to us. Being able to perform the service on set is essential."

What's in the truck?

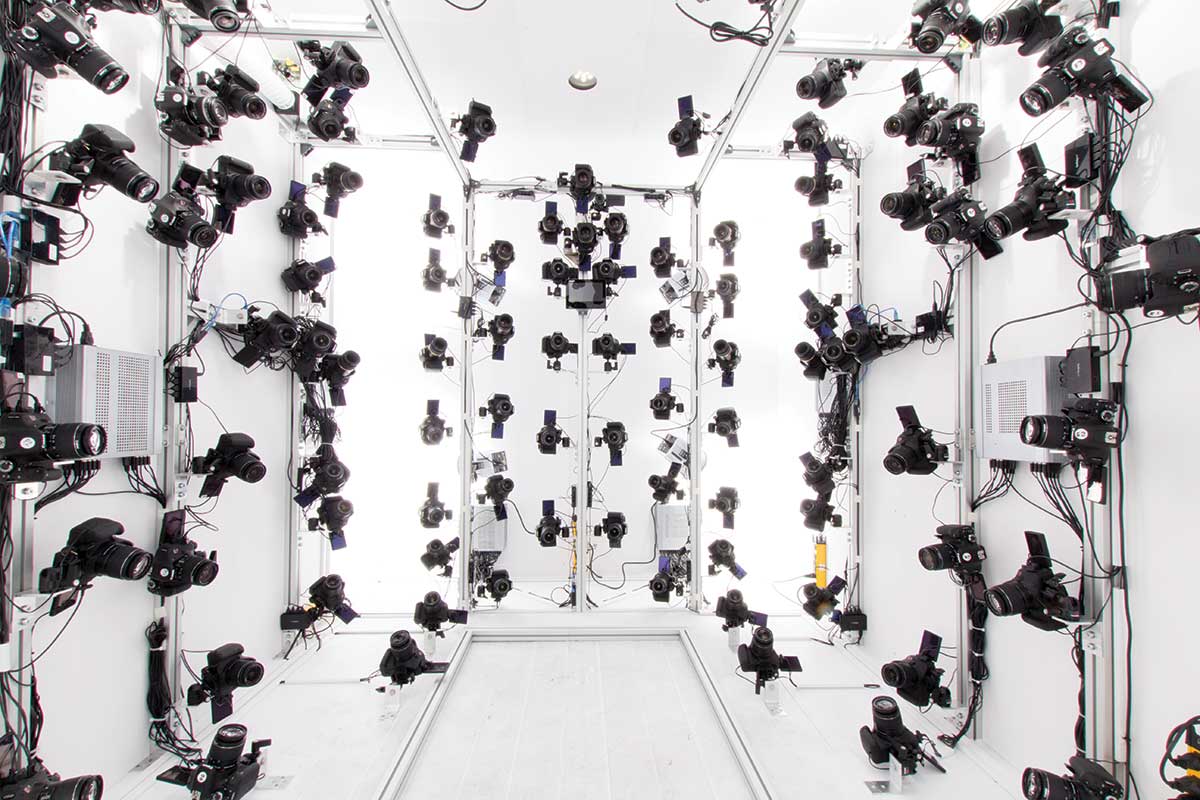

Pixel Light Effects' photogrammetry rig, contained in a modified Mercedes-Benz Sprinter van, is made up of 144 Canon DSLR cameras. These are all synchronised using a proprietary 'Camera Hub' device, which supplies power and triggers 16 cameras at once.

"It's designed to be daisy-chained together, so we use multiple devices to trigger the larger array," explains Zhang.

Lighting is an essential part of the photogrammetry rig. For this, multiple flashes and bounce light ensure that there is enough depth of field in the resulting images, and that the actor is lit evenly. The van interior is also decked out in white and the environment is calibrated so that it is as diffuse as possible.

The camera positions inside the rig were R&D'd by Pixel Light Effects for several months before an optimal layout was reached. "Everyone who does photogrammetry knows you just can't have enough cameras," notes Zhang.

"You always want more. Having a constrained budget and space means we must have just enough coverage at every angle."

Inside a scanning session

When an actor comes into the truck for a scan, Pixel Light Effects typically has just two technicians running the scanning session. First they will ask the actor and on-set supervisors if it is okay for the actor to wear a hair net. "This gives a more accurate skull shape, which will be helpful down in the pipeline," explains Zhang. However, it may be crucial for an actor to retain their exact wardrobe, such as a helmet or a faux hairpiece.

For a full-body scan, the actor will be instructed to make an A-pose, with their elbows and knees slightly bent for rigging purposes. The actor's face is typically posed in a neutral way and then aligned with extra witness cameras.

The actual capture is like taking a photo, again highlighting the benefits of a photogrammetry rig. "The capture itself is as fast as taking a photo at 1/1000th of a second," says Zhang. "All the cameras are synchronised, which means we can scan animals – who of course don't stay still – as long as they fit in the capture volume."

Scan and deliver

The resulting photographs are simply raw images, but they are managed by Pixel Light Effects and ingested into photogrammetry software, typically Agisoft PhotoScan or RealityCapture. It is in here that a CG model is produced, essentially via the push of one button.

However, the company does also perform clean-up of the resulting model in ZBrush and Maya to generate a shaded or textured form. This tends to involve patching any holes of missed details and removing surface noise.

Pixel Light Effects will provide a client – such as a visual effects studio or the film production – with an OBJ model, JPG textures, FBX files, the raw images, a colour chart for grading, and the PhotoScan or RealityCapture project file for re-projecting textures (since photogrammetry is photography-based, the scans 'automatically' come with high-resolution textures, and these can help create additional fine detail).

Although the company is relatively new to 3D scanning, it is already busy on productions in both Canada and China. One recent addition to Pixel Light Effects' truck came from a suggestion it received after demonstrating the vehicle to members of the Vancouver visual effects community.

"Improvements were made [as a result of] a 'roadshow' we had," remembers Zhang, "where we added live view cameras and monitors, so that the VFX supervisor could communicate with the talent from back of the truck, while the talent was being scanned."

For as long as an audience demands movies that defy reality, you can rest assured that somewhere there will be a truck full of cameras, busy scanning an actor's features to transform them into something incredible.

This article was originally published in issue 227 of 3D World, the world's best-selling magazine for CG artists – packed with expert tutorials, inspiration and reviews. Buy issue 227 here or subscribe to 3D World here.

Related articles:

Ian Failes is a VFX journalist, who has written for a number of creative titles, including fxguide, Cartoon Brew, VFX Voice, 3D Artist, 3D World, Thrillist, Syfy, Inverse, Digital Arts, MovieMaker, Empire Magazine Australia, Develop, Rolling Stone and Polygon. Ian now runs befores & afters, a brand-new visual effects and animation online magazine.