What is beauty? And do we need it in art and design?

What is beauty? Is it really in the eye of the beholder? We ask the experts.

What is beauty? Well, beauty is a six-letter word, and a loaded one, especially when it comes to working in the creative industries, but, while there’s the old adage that it’s 'in the eye of the beholder', some argue that what is (and isn’t beautiful) is far from subjective.

The Oxford Dictionary defines beauty as "A combination of qualities, such as shape, colour, or form, that pleases the aesthetic senses, especially the sight." But we all know it’s more than that: we often say a person is beautiful, or that they have a beautiful soul.

Beauty, then, is nebulous – it isn’t dependent on certain aesthetic qualities, but has a deeper resonance that’s more about feeling than composition or colour. If it were that simple, we’d all make things that were universally agreed to be beautiful. (If you want to focus on your own creations, see our guide to oil painting techniques, or our how to draw tutorials).

What is beauty?

Maria-Alina Asavei is a lecturer and postdoctoral researcher in Russian and East European Department at the Institute of International Studies at Charles University in Prague and an independent curator of contemporary art. "We often fail to make clear what we mean by 'beauty', even if we use this word quite frequently, in all kinds of occasions, related to art or not," she writes in the essay Beauty and Critical Art: is beauty at odds with critical–political engagement?.

Asavei continues: "When we appreciate that something has beauty, we implicitly accept that X is a source of positive aesthetic value or positive aesthetic appreciation. In the history of philosophical aesthetics, there are many theories and definitions of beauty. Despite differences, most of these theories connect the experience of the beautiful with a certain type of pleasure and enjoyment."

Yet many would argue that by our very nature, there’s a certain universal set of indices that inform beauty. Alan Moore, a former designer and typographer who worked under the mentorship of letterpress guru Alan Fletcher and in roles including head of art at Publicis in London, now focuses his entire career on beauty in design, and its role in successful businesses.

However, his take on beauty isn’t about what something looks like: he often speaks about it in terms of Einstein’s Theory of Relativity, Dirac’s theorem, spirituality and the laws of nature. "At an atomic level, everything is connected; they dance and are attracted to one another at a nuclear level. The law of nature seeks things to be made of symmetry and harmony, and even in opposites they’re complementary: we have night and day, up and down. We’re all made of the same stuff molecularly, so we intuit beauty – we know it to be the life-enhancing force."

Get the Creative Bloq Newsletter

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

As a designer, your duty is to only bring good things into the world

As such, Moore sees beauty not just as symmetry, but as regeneration: the first law of thermodynamics, also known as Law of Conservation of Energy, states that energy can neither be created nor destroyed; energy can only be transferred or changed from one form to another. This is intrinsically related to good design. "It’s about the idea of bringing good into the world and regeneration," Moore says. "People really connect to the idea of beautiful people because it relates to values, it relates to ethics. You have to think about if someone asked you as a designer, 'Is that the most beautiful decision we could make?' If you see that, then as a designer, your duty is to only bring good things into the world."

Is beauty useful?

These are big concepts, but are increasingly ones that designers have to think about in times of climate crisis and political turmoil. They’re as crucial (and as such, as "beautiful") as how good their type looks, or which Pantone they’ll select.

It’s also about utility: Moore points out that "Mother Nature works with purpose in everything she does." In legendary designer Paul Rand’s 1947 book Thoughts on Design he stated that, "Ideally, beauty and utility are mutually generative"; the combination of both is when you reach the pinnacle of design. "Visual communications of any kind… should be seen as the embodiment of form and function: the integration of the beautiful and the useful."

While this doesn’t help us to define what is and isn’t beautiful, it does underscore the notion of beauty as being a concept we all understand, but that can be mutable and dependent on context. Asavei echoes this view: "What we know about an event or object and our world-view and moral values always determine our perception about what is beautiful, why it is beautiful, and what is not beautiful."

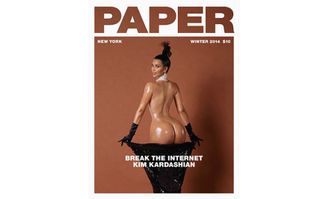

It goes without saying that what is and isn’t considered beautiful has changed throughout history, whether in art, design or the human form (for women in particular – think fetishising plumpness when it signified wealth during the Renaissance era; 90s "heroin chic" waifs; today’s Kardashian-esque big ass, little waist, big lips).

At one end of the historical beauty-definition spectrum is the "rational understanding of beauty and the search to boil down the essence into formulae and models for application," as Alan Powers, a design writer and professor of architecture and cultural history at the University of Greenwich puts it in Beauty: A Short History.

This was seen during the Renaissance when the prevailing belief around beauty was that it was based on numbers "akin to the harmonies of music and the movements of the planets". At the other end is a far more romanticised notion, such as the Middle Ages’ view of beauty as part of the "divine order" or poet John Keats’ "beauty is truth, truth beauty" from his Ode on a Grecian Urn.

Then Modernism came along: everything was stripped back to its most basic components and that continues to play a huge role in today’s frequently Swiss-leaning, grid-loving design education. It was the far-reaching cultural shifts (at least in the Western world) of the rise of Modernism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that saw the earlier decorative values of pattern and opulent lettering styles in print, or the decorative flourishes of architecture that had formerly dominated, fall out of favour. It also saw a swift shift toward pared-based design and prioritised rigid proportions and functionality.

This marked the start of an underlying reluctance to embrace beauty as a core value, which continues to this day. The idea of beauty, to many, is (perhaps subconsciously) seen as trite or old-fashioned – an aesthetic principle at odds with the rigid frameworks of 21st century design. The divisive Guardian art critic Jonathan Jones wrote a piece in 2012 about the rejection of beauty in contemporary art, which aligned this view with far older beliefs that "beauty is the most dangerous idea in art… It tantalises and confuses, inspires and crushes", and that "beauty has been worshipped as the highest artistic value and denigrated as a pagan temptation."

The value of beauty

Yet in design, it’s not so much about "pagan temptation" or danger, but a focus on problem-solving, form-following-function, conceptual rigour and evolutions in technology that drive how interfaces, software and even print design are viewed. As grids and rules came in, beauty in its more traditional sense went out. As Alan Powers puts it, "The ideal of pure geometry remains deeply rooted in western consciousness as the basis of beauty. It sits well with the idea that beauty is an expert business, not accessible to the untrained mind."

However, one designer who consistently rails against the notion that beauty is unimportant, subjective or "not accessible to the untrained mind" is Stefan Sagmeister. In his talks and the book Sagmeister & Walsh: Beauty, created with Jessica Walsh, he uses numerous scientific and cultural examples to point out that beauty is far from being "in the eye of the beholder" (he points out the phrase only came to prominence thanks to a line stating as such in Margaret Wolfe Hungerford’s 1878 novel Molly Bawn.)

In talks, Stefan has shown his audience a slide with five different colours, another with five different shapes, and asked people to vote for their favourite. The results are almost identical wherever and whenever he does this (turns out circles and blue or purple come out top). Sure, it’s a crude experiment, but it says a lot about how our tastes are not as unique or subjective as we might have thought. Stefan often blames Modernism for the devaluation of beauty, and the suspicion that beautiful work might not be taken seriously, or derided as merely decorative or commercial.

To avoid this risk, the grid was firmly laid out in design schools as the safe, clean, rational solution, to the point that it became non-expressive to the exclusion of physical beauty. Jan Tschichold – one of the most famous proponents of Modern ideals through his Die Neue Typographie – eventually went back on his espousal of modernist values, describing Modernism as "inherently authoritarian and fascist", and a style that had become a "default" that lacked wit and innovation.

The public will respond to any attempt to rehabilitate beauty

Jan Tschichold

Although his text is still a staple in design education, Tschichold went further, saying that a designer doesn’t have to be inventive or innovative to create design work based around the grid. Despite this apparent ongoing renunciation for many designers of beauty as a priority, "there is every reason to work with it again," says Powers. He cites MORI research that showed "the public values beauty and not only wants it in their homes, clothes and other personal belongings, but also in the great outdoors, the public realm and public life… especially in these difficult times, the public will respond to any attempt to rehabilitate beauty." Designers, take note!

Alan Moore’s views echo this, and make a case for the importance of beauty in commercial design: "Beauty is a powerful quality for a business to have," he wrote in The Business Case for Beauty, originally published in Management Today. "People experience the world qualitatively, not quantitatively… a Temkin survey shows that customers with a positive emotional experience of a company are six times more likely to buy more, 12 times more likely to recommend and five times more likely to forgive a mistake." This, clearly, defies any suspicions that beauty in creative work has no function, or serves a merely decorative purpose.

Alan Moore’s commitment to preaching the values of the beautiful was born of a "road to Damascus" moment, he says. This arrived after many years working for various organisations and agencies and his view that there was a "form of myopia in the way they were working: making money at any cost until it cost them everything," he says. "I got very angry at the greed across incumbent industries, whether they were TV, radio or print. I thought ‘this is not okay, we’re supplanting the idea that a good life is one born out of material consumption – nothing to do with the wealth of life’."

If there are so many cases in favour of beautiful design, why then in recent years and even decades have we seen designers move towards not just function over form, but deliberately "ugly" design: the post-ironic clashing of typefaces and so on? We’d suggest that this is because such work isn’t in fact ugly at all when it’s done well, but what we mean by beauty has radically shifted.

Nature and beauty

Alan Moore points out that if everything in nature is beautiful, and that nature thrives on diversity and regeneration, then how we view what is and isn’t beautiful or aesthetically appealing will patently shift over time. Therefore, the notion of beauty as either a representation of subjective, aesthetic pleasure or something purely aesthetic with little intellectual or conceptual underpinning, is something that the designers who consider their role as simply "problem solving" might want to rethink.

Indeed, Jonathan points out that artwork that shuns beauty may well be in vogue; but once we’ve "look[ed] at it earnestly," we then go and look at gorgeous photos, films, magazines – the true art of our time." With so much of the commercial creative landscape responsible for such imagery, this suggests that a great editorial layout or careful selection of typefaces, a well-art directed campaign, or even a brand film has as much need for beauty as an artwork simply created for art’s sake.

One newish platform pushing radically new and innovative ideas around what’s beautiful is Dazed Beauty. Launched in late 2018, and art directed by Ben Ditto, who’s also creative director of Ditto Publishing, with creative direction from Isamaya Ffrench, the pair brought a more internet-led, fantasy-like, occasionally gore/horror-inspired look to the platform.

The platform stated its mission as "celebrating identity, self-expression and creativity through the transformational power of beauty." This means alongside covering faces and products, there’s a considerable focus on art. Pieces range from the sexuality of maternal women to nipple removal and other "extreme body modification" to profiles on creative coders and an artist who claims that we’re "already living in a video game".

Beauty is personal, and platforms like Instagram have helped people to leverage beauty on their terms

Nellie Eden

This idea of creativity and self-expression as integral to beauty has meant the design of the site is thoroughly futuristic, using gloopy metallic type that floats around the pages, lurid neon green lines to break up the site’s grid and sections that are predominantly image-led, clearly taking a cue or two from certain image-sharing platforms. It’s a far cry from the usual look of beauty or fashion publications: all clean, neat layouts; white space, femininity and mastheads set in black, traditional serif capitals. "This is beauty for the social media age," as Ffrench puts it.

"Beauty is personal, and platforms like Instagram have helped people to leverage beauty on their terms," says Dazed Beauty’s editor Nellie Eden. "Our design is informed by the convergence of the beauty and the tech industries. When we talk about beauty it’s not about products or who’s the face of YSL – it’s what a teenager in Poland is doing with his contact lenses."

Eden continues: "Dazed Beauty has a distinctive personality: you can put something on Instagram that people find disgusting or appalling or strange, and that’s fantastic, because beauty imagery has become so sanitised and so far from what it means to be human… We always say make it weirder or more digressive or obscure." These presentations of future-facing, deliberately "weirder" or "appalling" takes on what is beautiful doesn’t mean that beauty needn’t be a consideration for designers – quite the opposite – but it does mean they need to dig deep to think about what could make their work more beautiful, and their approach to doing so.

Beauty, states Powers, is "cultivated through a deeper understanding of what we already have, and by looking after and appreciating the unique characteristics of the places where we live." He adds, "we should commit ourselves to living better on less. Perhaps the key thing is to have the confidence to say beauty matters, and not to be afraid of the reaction." But it’s not just about these deeper philosophies, or trend-bucking.

In Sagmeister and Walsh's book, they state the case that attention to form (in other words, beauty) in turn makes a design more functional. Beautiful packaging design, for instance, sells better. Moore firmly backs this: "Beauty as a frame, philosophy, language even, shows how to build businesses that are more relevant and needed in the world we all live in today: businesses that build legacy, that go beyond sustainability, that are places the best people want to work for, and that deliver outstanding customer experience, all of which translates into long-term growth and profitability."

Alan Moore also argues that rather than form making something more functional, "beauty flows from purpose", citing companies such as Patagonia as exemplary in attracting creative talent and effective decision-making and leadership through the sense of purpose embedded across the business. To him, beauty isn’t just about design or even design teams: it’s about a workplace culture built around generosity and positivity. This in turn brings deeper engagement with the tasks at hand, trust and overall better well-being.

It’s also about sustainability, for both the business and the world: Moore states that "beautiful businesses… take less, make better with less and waste nothing" – they are "regenerative, existing as part of living systems rather than trying to disrupt or destroy them." Moore adds, "Beauty isn’t incompatible with rigour. It won’t hurt your bottom line or your return on equity to have a beautiful business with a beautiful culture, making beautiful products. Indeed, in the long term it could be one of your greatest assets."

To make more beautiful design runs deeper than the images you put into the world, it’s about the social purpose of what you’re doing and how you’re running your creative business. So if we run with the idea that beauty remains vital to design, but the foundations of what is seen as "beautiful" are more mutable than ever, how as a designer do you make more beautiful work?

Describing beauty as "the sweet spot between order and chaos" (rather than the Modernist designers’ rejection of chaos of any form); Sagmeister and Walsh use the equation M = O/C to decide on something’s beauty (beauty, M, is the ratio of Organization (O) to Complexity (C).) Whether a commission requires simplicity, ornamentation or boundary-pushing image-making, beauty is, and always will be vital.

In an age where designers increasingly see AI and other tech innovations gradually making gains on the grub work of design, one thing that computers will never be able to do is judge an innate, more nebulous sense of what is beautiful. Beauty is innately related to humanity, and whatever face you put on it, computers will never be truly human.

This article originally appeared in issue 300 of Computer Arts, the world’s leading design magazine. Buy issue 300 or subscribe here.

Read more:

Thank you for reading 5 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Emily Gosling is a freelance art and design journalist currently writing for titles including Creative Review, Eye on Design, Creative Boom and People of Print. She’s previously worked at Elephant magazine, It’s Nice That and Design Week, and was editor of Type Notes magazine. Her book Creative Minds Don’t Think Alike was published by Ilex Press in 2018, and she also plays bass as one-quarter of the eight-titted beast, Superstation Twatville.