Sustainable design: the ultimate brief

Sustainable design is fast becoming essential, and not just to do good for its own sake. As Anne Wollenberg finds, sustainability can be a rewarding creative challenge, not an inconvenience

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

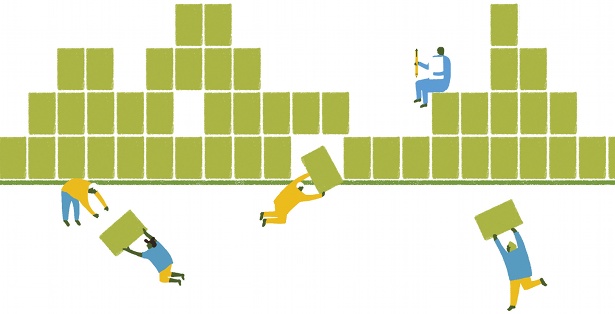

Sustainable design may be a modern-day buzz word, but according to Seymourpowell’s Chris Sherwin, it is too often viewed as “the guilt trip you have after doing the wrong thing”. In fact, with the right approach, it can be a rewarding design brief in its own right. As an industry that is both creative and wasteful, design has the power to become a pioneer or a scapegoat, if not both. Or, as experience designer and sustainability expert Nathan Shedroff puts it, design is the problem – but it’s also the solution.

“Clients often look to designers for leadership,” continues Sherwin, in his role as Seymourpowell’s head of sustainability. But if designers are to take the lead and encourage their clients to embrace more sustainable practices, it’s important to clarify what that actually means – and what it doesn’t. Sustainability is a process, not an absolute: “It’s a spectrum of activity, from making tiny alterations at one end, like changing how you run your studio without touching your design processes, right through to designers who only take on projects underpinned by sustainability.”

“Personally, I prefer to use the term ‘environmentally preferable’, because there’s not really any such thing as being green or sustainable,” reflects New York-based designer and sustainability consultant Naomi Pearson. “It’s more realistic and attainable to try and lessen the impact that you’re having. The more you can do, the better.”

Material decisions

“There are two knee-jerk responses to sustainability that I continue to hear,” Pearson continues. “The first is that people assume that sustainability costs more, which isn’t true if you’re paring things down and getting smarter and leaner. And the second is that they think it’s simply about swapping material A for material B.”

For a basic starting point, Sherwin suggests examining your housekeeping practices, such as energy efficiency and recycling. “The next step is to make yourself aware of material decisions, like paper stock, printing processes and distribution,” he explains.

“You might bundle this best-practice together and write sustainability into your design briefs or processes. Then you can look for projects where you’re applying your design skills to sustainability as subject matter,” Sherwin goes on. “Ultimately, you need to use your best tools to champion the cause.”

That’s just the beginning, of course. “Everyone needs to get out of their silos and talk to people,” argues Nat Hunter, co-director of design at the Royal Society for the encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce (RSA). If you’re designing something using plastic or paper, go to the place where it’s made, and where it’s going to end up being recycled.”

Hunter explains that it’s important to pay attention to the entire life cycle of the products you’re designing. “Talk to material scientists and recovery centres if you’re designing anything that’s going to go out into the world, and ask yourself if people will know what to do with it at the end of its life. If you’re designing a website, gen up on data centres.”

Hunter believes the design industry needs to move towards four key solutions. “Design for longevity by making well-designed products that last and are fixable, repairable and upgradeable,” she begins. “Design for service by creating products that can be shared and leased; design for re-use in remanufacture; and finally, design for disassembly.”

Print versus digital

When Hunter created the 2011 D&AD Annual, working with AllofUs founder Sanky – the then-president of D&AD – and Pentagram designer Harry Pearce, the project started with the question of whether to produce a printed book or to go for something digital. “The brief was to create the most sustainable annual ever,” she recalls.

There’s a natural tendency to assume that digital design is more sustainable, but this isn’t necessarily true. Just think of the power consumed when you load up a website, from the device on which you access it to the data servers on which it’s stored, as well as the manufacturing practices involved.

Hunter mentions Julie’s Bicycle, a sustainability organisation that carried out a carbon assessment of both routes – print and digital – and found the results were much the same. The digital route was also far less certain. “We know people will use a book in the same way in the future,” she explains. “The D&AD Annual justifies existence in the real world, because people treasure and keep them for a long time,” she adds.

The aim, then, was to reduce everything they possibly could, while paying attention to the product’s full life cycle. “We got really forensic about every single detail,” she recalls. “The main issues were paper, energy and transport.” For example, they moved printing and production processes from China to Europe, used 40 per cent less paper, and avoided plastic or toxic inks to ensure the Annual was recyclable and biodegradable. “We used far fewer resources, but still maintained our integrity.”

“There are all sorts of interesting ways to save money,” Hunter adds. “You can always bring things in under budget if you use a bit of creativity and work with your printer. Some firms, like Calverts Co-operative, are brilliant at that.”

“Talking to a good printer can really help,” agrees Daryl Campbell, partner and creative director at Belfast studio Meadow. “Having conversations with a field expert is always the best way to move forward. Sometimes you can save money by doing small things: using money saved on printing to purchase more eco-friendly paper stock, for instance.”

That said, some clients simply want to save money. Budgets are always going to be a concern, especially in the current economic climate. “Now austerity has kicked in, people are often looking for the cheapest, rather than the best, option,” continues Campbell. “There’s a definite trend towards that at the moment, but hopefully it will change in the future.”

Bottom line

“Nobody’s going to say: sustainability isn’t important, I don’t care about that,” says Pearson. “But as far as making it happen and putting a working solution on the table, it needs to meet the bottom-line criteria. Getting leaner enables things to be taken apart more easily at the end of their lives. It’s also cheaper, which is easy to sell to a client,” she says.

For Pearson, who creates a lot of exhibition graphics in her day job as a designer at the Wildlife Conservation Society, new materials are a potential stumbling block. “It’s a risk to use a material that doesn’t have a long track record,” she says. “Some projects are more suited to experimentation however, like those involving indoor graphics.”

Pearson has created a clear system, including storage areas and expiration labels, to communicate information about whether materials can be reused or not. “We have a system in place now, and it saves money. It’s organised and it’s a way to make sure that things don’t just get thrown away.”

There’s a clear moment of letting go involved, she adds. “You don’t know who’s going to be around in 20 or 30 years, so the best thing you can do is build something that can be easily taken apart, use mechanical softeners instead of heavy-duty adhesives, and make things modular so you can replace parts rather than the whole. That way, it’s all set up to be updatable or easily recycled.”

Future planning

After all, we can’t predict what resources will be available in the future. “We don’t currently have landfill sites that are managed to allow compostable material to decompose,” says Pearson. “That system might be in place in the future. You need to plan for the best-case scenario and design things that can be broken down, recycled or composted.” According to Pearson, much of it comes down to asking the right questions: “Do that and you’ll soon start to see where the holes are and where you need to dig a little further.”

“Sustainability could also move forward faster if designers were better at trying new things and documenting them, sharing success stories and case studies,” she adds. “If we were just a bit more honest and willing to share what works and what doesn’t, we could collectively start to build a knowledge base.”

Meadow is currently in the process of developing a green map and business directory. “This will be an online tool for companies and individuals to sign up to,” says Campbell. The idea behind it is transparency – being committed to sustainability means being completely open about what you do and how you do it. “It’s about the ethics of the companies you work with,” he says. “You need to get to know them and dig that bit deeper.”

Discover 15 amazing examples of experimental design at Creative Bloq.

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

The Creative Bloq team is made up of a group of art and design enthusiasts, and has changed and evolved since Creative Bloq began back in 2012. The current website team consists of eight full-time members of staff: Editor Georgia Coggan, Deputy Editor Rosie Hilder, Ecommerce Editor Beren Neale, Senior News Editor Daniel Piper, Editor, Digital Art and 3D Ian Dean, Tech Reviews Editor Erlingur Einarsson, Ecommerce Writer Beth Nicholls and Staff Writer Natalie Fear, as well as a roster of freelancers from around the world. The ImagineFX magazine team also pitch in, ensuring that content from leading digital art publication ImagineFX is represented on Creative Bloq.