Get to grips with UX theory

UX theory can help you understand users' motivations and strike a balance between needs and expectations.

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Five times a week

CreativeBloq

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Once a week

By Design

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Once a week

State of the Art

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Seasonal (around events)

Brand Impact Awards

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

A good grasp of UX theory is vital for anyone researching, testing and designing user experiences. There's no magic solution for user experience design, and no simple test to uncover quick-fix solutions that guarantee users will engage with a product the way you intend.

UX theory does involve science – and one that's been around for a lot longer than the digital experiences we often associate UX design with today, dating back to well before UX became a relatively common term. Like any scientific theory, it begins as a hypothesis, such as why is a specific event happening? And this hypothesis must be tested by collecting data that may validate or invalidate it. This can be done via UX testing for example. Only after that does the hypothesis become a theory.

To learn the key fundamentals of UX theory, UX design and more, sign up for our online UX design course. If you're exploring UX theory for work on a website, the best web hosting services can help with analytics. Also, since testing UX theory often requires a lot of data, you might want to make sure you have the best cloud storage to back up your information.

Why is UX theory important?

A theory is a validated explanation of why something is happening, free from bias. It’s based on factual data collected through a replicable method, not just on what the loudest person in the room believes. Without that structure, it’s all too easy to run a test and succumb to confirmation bias or data manipulation in order to get the feedback you want. That’s not how science works.

In UX, we don’t control the outcome. We aim to create a means to communicate the complex nuances of user behaviour in a simple way, and sometimes the data proves us wrong. And that's fine: our goal isn’t to always be right but to uncover the facts.

UX theory: data solutions

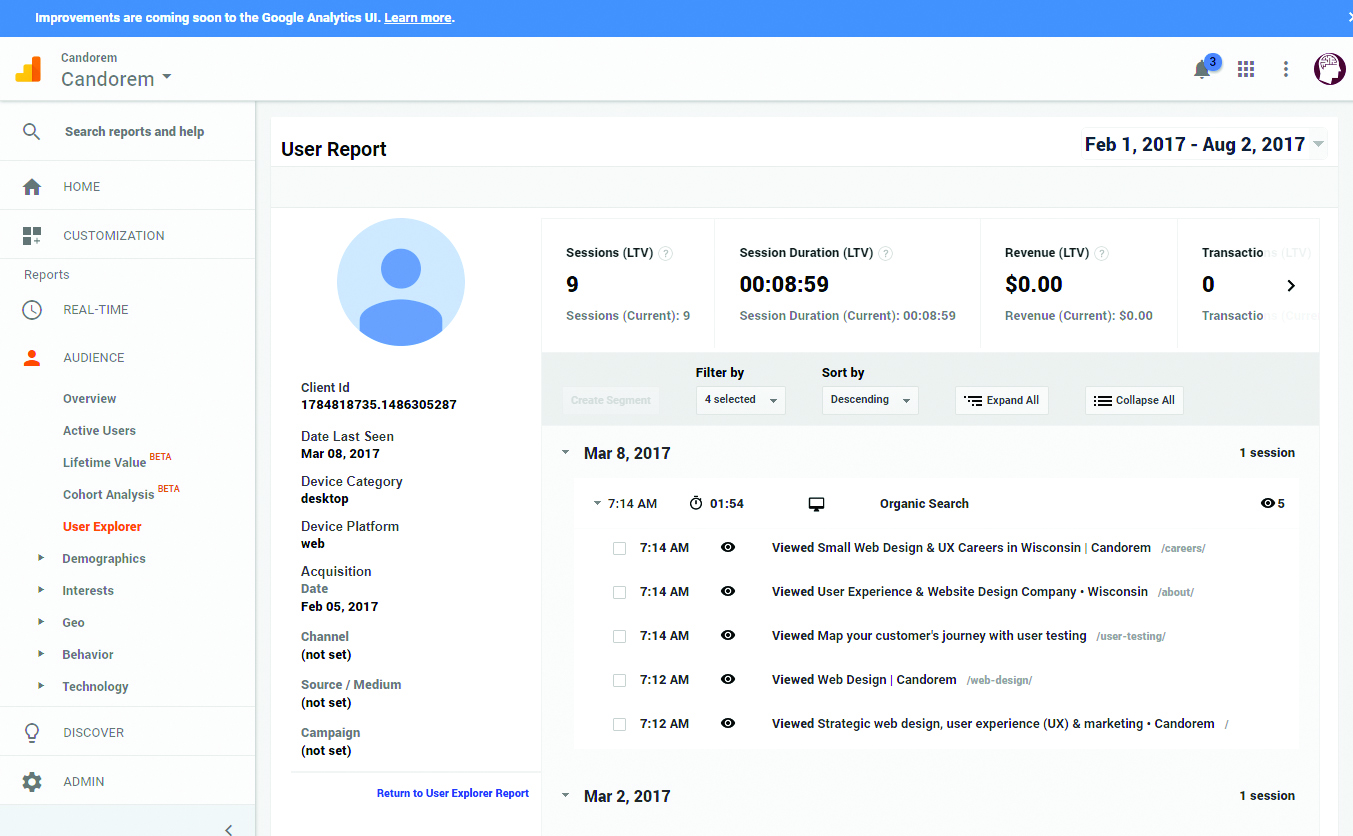

For the data you need to validate a theory, user data solutions like Google Analytics can be a good first start, but they rely heavily on assumption. You can export records and use a service like IBM Watson to find correlating trends, but don’t confuse data with fact. Predictive modelling or assumptions don’t answer the golden question of 'why?', and the central focus of UX is to discover why a user is motivated to take an action.

This is the inherent problem with user experience. Everyone thinks they have the answers, which results in UX being led by perception bias. For example, the sales team might think it knows what customers want to buy while the marketing team thinks it knows how to convince customers they want it. Management has an approved budget based on what they assumed the teams would need a year ago and that probably didn’t include an allocation for UX research.

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

In this situation, each department or employee has a view on what should be done based on their own experience with customers. The problem is that they’re all right, but they’re also all wrong. Organisations that fall into this perception trap often find themselves trying to please everyone to avoid a conflict, and that ends up serving no one.

The job of UX theory is to remove this bias and help the group understand the bigger picture: the customer's needs and expectations. So how can we reframe the conversation and make it less about opinion? This is where we need to let the data do the talking.

UX theory: collecting data

The process of collecting data is quite often misunderstood. Data collection to validate a UX theory doesn't need to be devoid of emotion, nor does it need to focus strictly on usability. What it does need is to have a purpose (see our 5 tips for successful UX research and testing for more pointers here). So what kinds of data are you collecting and why? As you probably know, there are two core types of data:

- Qualitative: Non-numerical, emotional feedback from participants – think first reactions or personal opinion-based feedback. What you liked and why, and descriptions instead of numbers. Qualitative = quality.

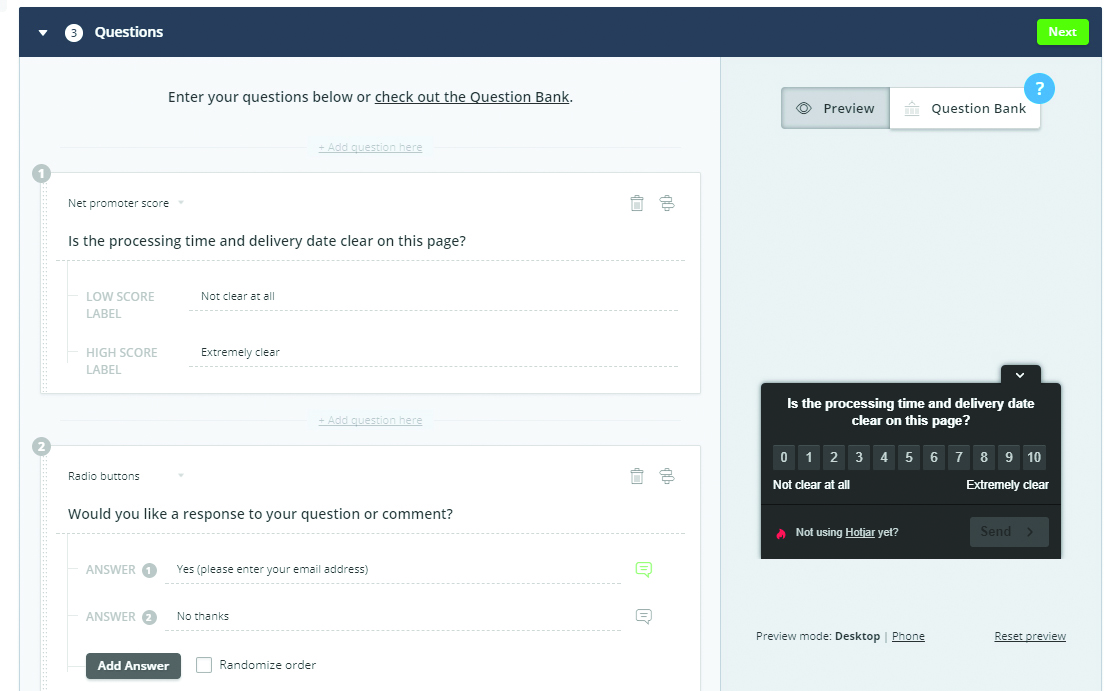

- Quantitative: Numerical, scientific feedback, for example 'Perform this action and rate the ease of completing the action on a scale of one to 10'. This is the basis for systems like Net Promotor Score (NPS). Quantitative = quantity.

Quantitative data

If you’re given the task of creating a baseline for customer satisfaction on member sign-up or at the checkout of a shopping cart, you'll need to have quantitative data. This gives you unbiased numbers that show a clear progression from where you began to where you ended months or years later. This is crucial to show the importance of investing in UX.

Many organisations will see the initial improvement but not understand the value in retesting. An increase in signups or revenue or a drop in support requests is fantastic to see, but there are many variables that could influence the results. Attribution is your friend. It’s also the friend of the departments that you will be working with to showcase explicitly that the testing performed and subsequent changes were validated.

This goes back to the scientific validation we discussed earlier. Collect the data, make the change and validate that the change was accurate. If it wasn’t, create a hypothesis as to why it wasn’t and start again. The trick is to always try to prove something wrong.

Qualitative data

If you’re redesigning a consumer-facing website without a long-term UX plan it may be okay to focus on qualitative feedback: descriptions and emotions. This works well for design-centric UX like landing pages for marketing or blogs. However, it doesn't work well for long-term strategy as trends are fluid. What works today for a tested demographic may not work well next year, so care is needed.

Qualitative feedback is harder to shape into strategy because what users say they want and what they actually want are very often two different things. It requires a lot of foresight to peel back the layers of feedback and dig deeper with follow-up questions or facilitation to get what you need.

Without the context of motivation, you become trapped in a feedback loop, which tends to lead to the perception trap again. If you’re stuck without direction, you'll try to find meaning in the data by applying bias. Once that happens, you focus on the wrong meaning and the data becomes useless.

UX theory: finding the right meaning

Another point on data is that you need to ask the right questions to find the right meaning. Take another example. Tenants in a New York office building are complaining because they believe that too much time elapses between pressing the button for the lift and the elevator arriving and opening. Several tenants say they want a faster elevator to solve the problem and threaten to move out if they don't get it.

Here we have qualitative feedback and an emotional response. Management has requested a feasibility study to determine cost and effectiveness, which means hard numbers and quantitative data. Meanwhile, a different perspective from someone in the psychology field has focused on the tenants’ core needs by digging deeper than their initial feedback. They ignored the numeric feedback of the financial study because it wasn't cost-effective to replace the elevator and rebuild the structure to accommodate the tenant’s suggestions.

Instead, the psychologist determined that finding a way to occupy tenants’ time would offset this frustration and suggested installing mirrors in the landing area. Due to the low cost of this potential quick fix, the manager agreed to see what would happen. Incredibly, the complaints stopped. Now you see mirrors installed in hotels and office lobbies all over the world as a cost-effective way to appease the frustration of elevator users. The case just goes to show that your data is only as good as the questions you ask.

UX theory: asking the right questions

So what are the right questions? Let’s assume you're in the process of redesigning a website for a client. You’ve been asked to perform a user test to help define the direction the design needs to take – we're talking broad stroke details: colours, fonts, layout, sizing and so on. You propose a qualitative test.

But don’t compose a questionnaire for the survey without thinking first about how a user may respond. You need to formulate your hypothesis first, because it provides vital direction. If you want to collect feedback on three website homepages you could run a set of questions and repeat them for each. The repetition is important for collecting similar feedback on each website. But what question would you ask exactly?

If you test 10 participants and eight of them come back with completely different feedback, it makes your job harder than it needs to be and introduces the risk of falling back on bias to prioritise the data. Instead, you need to ask very pointed questions to get actionable feedback.

- Instead of asking 'What do you like about the homepage?' ask 'Without scrolling, do you know what this website is marketing?'

- Instead of asking 'What do you like about the menu navigation?' ask 'Looking at the menu, is it clear this website has information on careers?'

You also have to factor in how you propose the questions. Is the question leading towards the goal itself?

Consider this example:

- Leading: 'Find the careers link in on the top of the page. Click on it to view information about the available careers.'

- Less leading: 'What link at the top of the page would you click on to view information about the available careers?'

- Ideal: 'How would you expect to locate information about the available careers on this website?'

Instead of guiding the user towards a goal, the ideal question puts the decision-making on the user. From this, you will get a better understanding of how that user, and their specific demographic segment, will expect to navigate the website. If you asked one of the first two questions you lose that data. So, it’s not always about the question you ask, but how you ask it that defines the result.

If you are unable to compose such defined questions, you are moving too quickly through the process. Take a step back and think about the pain points of the users in which you’re trying to communicate. Each decision you make should be working toward providing an effective solution for not only the business but their customers as well.

Organisational UX maturity

Businesses and other organisations all have different levels of UX maturity, and knowing that can help you worth with them a lot more smoothly. At Candorem we have a simple system for understanding the UX maturity of our clients. This enables us to quickly define the need for additional data collection, what type of data to collect and how quickly we can begin providing guidance.

It’s also a great way of understanding the existing perception of the value of investing in UX. This can also break down into four core levels of data that they will have available for us to start assessments.

- Level 1 data: Google Analytics and heatmaps

- Level 2 data: Curated customer data (email, gender, location and purchase history by customer segment)

- Level 3 data: Customer survey data (likes, dislikes, ratings and interest levels), anonymous website recordings

- Level 4 data: User testing sessions, customer persona profiles and quantitative data

Businesses will have some variation of the above. If they don’t, get them set up with Level 1 and allow adequate time for collection of some low-level data. Mining this data is crucial in creating your own hypothesis. When an organisation unfamiliar with the nuance of UX defines the goals for a project without supporting data to guide them, it limits the potential outcome. Setting a goal is easy, but defining the right path takes time and experience.

Increasing revenue is not a goal, it’s an idea. Set specific goals like increasing revenue ten per cent for a segment of customers aged 24-35 that are shopping for a specific category of product. This consists of specific requirements that can be tested to generate a hypothesis, validated to create a theory and initial baseline, and then retested to validate the plan for growth over time.

User experience is about understanding the needs and expectations of your customer and collecting the necessary data to tell the story in an unbiased way. For more on UX see, our 10 steps for creating engaging user experience.

Want to learn more about UX theory and UI design? Find out about our online UX Design Foundations Course.

Related articles:

Joshua has worked with agencies and Fortune 500s to refine UX strategies for nearly 20 years. He founded Candorem to lead UX execution through partnerships within established organisations.

- Joe FoleyFreelance journalist and editor