Does creative freedom actually exist?

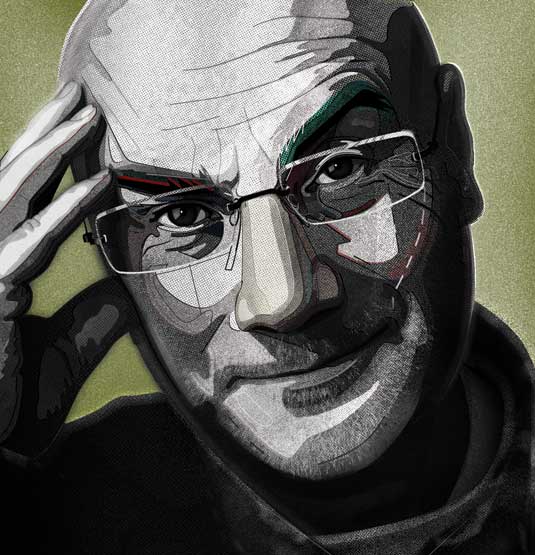

Adrian Shaughnessy considers what the Charlie Hebdo cartoon horror story tells us about the power of imagery and creative responsibility.

Three months on from the Charlie Hebdo tragedy, graphic designer, writer and publisher Adrian Shaughnessy reflects on the meaning of 'creative freedom'…

The notion of free speech is enshrined in Western democracies. But you only have to think of Wikileaks and Edward Snowden to know that our leaders merely pay lip service to the concept. It's the same with us, the general public. Very few of us in the West say we don't believe in freedom of speech.

But what if you picked up a magazine with a drawing on the cover poking fun at a disabled person, or a rape victim, or someone from a racial minority? Most people in the West think that these are targets that should not be held up for ridicule or satirical comment.

So why do we disapprove of Muslims objecting to drawings showing the Prophet Mohammed indulging in sexual acts? Of course, in the West we rightly find murder a wholly unacceptable response to blasphemy. And the overwhelming majority of Muslims agree that what the Charlie Hebdo assassins did was un-Islamic and inhuman.

But we know why it happened, and we know that someone growing up in an Islamic community in Europe who sees his or her adopted country at war with Muslim countries, does not have the same worldview as Westerners.

Satirical commentary

Imagine now that we pick up a magazine and it contains a front cover drawing showing David Cameron, Ed Milliband, Nick Clegg and Nigel Farage having group sex. Or the Pope, the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Chief Rabbi at a swingers party.

Sure, some people will be offended, but only a minority would want these drawings banned. The rest of us would enjoy the satirical commentary inherent in the drawings – and none of us would want the cartoonists murdered.

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

Why are these covers different from the first batch? The targets of the second group – senior politicians and religious leaders – have influence and authority. The targets in the first batch are people who can't fight back – the disabled, victims of sexual violence, and racial minorities.

The covers in the first group trespass on areas of life that we agree are beyond the reach of jokes. In other words, there are things that we cannot say, and it is therefore hypocritical of us to lecture others on free speech.

Causing offence

This takes us to the heart of the Charlie Hebdo nightmare. The drawings that offended Muslims are an attack on a religious minority within Western culture.

It would be wrong to say that Muslims in the West are entirely powerless. Some Western governments have Muslim cabinet ministers. But huge numbers of Muslims live in rundown areas of major cities, are often poorly educated, and are obliged to live in countries at war with their homelands.

So what can we, as practitioners in the creative industries, learn from Charlie Hebdo? While few of us in the creative industries are engaged in depicting satirical images likely to get us shot, it is myopic to say that our work has no impact on wider culture.

Design is not a frictionless activity. Most of us are busy creating the imagery and visual collateral for our consumerist, ultra-materialistic society. We do this without aiming to cause harm.

Unforeseen consequences

But we cannot say that our activities are without consequences. In the eyes of many around the world, our work creates the images of Western abundance, pictures so powerful that they form one of the factors (by no means the only one) that causes thousands of people to risk their lives to get to the West to share in the largesse.

Not only that, but the people we exclude from this world of abundance – the ghettoised, the poor, the uneducated – are more inclined to lash out at those that appear to hold all the wealth and power.

As designers and creative practitioners we can say this has nothing to do with us, and that we have no power or influence. Yet we are quick to claim the credit when our work is successful. This is hypocritical. We can't have it both ways.

If the Charlie Hebdo horror story teaches us anything, it is an extreme and horrific example of how acts of creativity can sometimes have repercussions in ways not intended.

Words: Adrian Shaughnessy

In 1989 Adrian co-founded design company Intro. Today he runs ShaughnessyWorks and is a founding partner of indi publishing venture Unit Editions, producing books on design and visual culture.

Will the Charlie Hebdo murders impact your work? Have you self-censored in creative projects? Tweet your thoughts to @ComputerArts using #DesignMatters. This essay first appeared inside Computer Arts 237: Pick the Perfect Typeface.

Liked this? Try these...

- How to manage your freelance cashflow

- Artist reinvents the normal on a quest for new ideas

- 13 secrets for creating game-changing branding

The Creative Bloq team is made up of a group of art and design enthusiasts, and has changed and evolved since Creative Bloq began back in 2012. The current website team consists of eight full-time members of staff: Editor Georgia Coggan, Deputy Editor Rosie Hilder, Ecommerce Editor Beren Neale, Senior News Editor Daniel Piper, Editor, Digital Art and 3D Ian Dean, Tech Reviews Editor Erlingur Einarsson, Ecommerce Writer Beth Nicholls and Staff Writer Natalie Fear, as well as a roster of freelancers from around the world. The ImagineFX magazine team also pitch in, ensuring that content from leading digital art publication ImagineFX is represented on Creative Bloq.