The rebirth of the zine

Zines are bringing back the '70s and '90s, with a chaotic, cut 'n' paste aesthetic.

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

The zine aesthetic – both visually and conceptually – is the ultimate manifestation of ripping it up and starting again, the idea that formed the core of punk culture, post-punk culture (we have Scottish post-punk purveyors Orange Juice to thank for the popularisation of the phrase), and youth culture more generally.

What are zines?

The word zine is simply a shortened version of magazine, or more usually, fanzine, but in its snappier, four-letter form it has far more significant connotations. 'Zine' – at least, in its origins – speaks of bedroom activism, of punk, of the dissemination of ideas that otherwise may not be circulated: those around queer sexualities perhaps, or underground music scenes, or simply fandoms so niche there isn't a hope in hell of seeing them in print-titles-proper.

If you'd like to explore more examples of innovative design, check out our pick of the experimental design that's pushing boundaries.

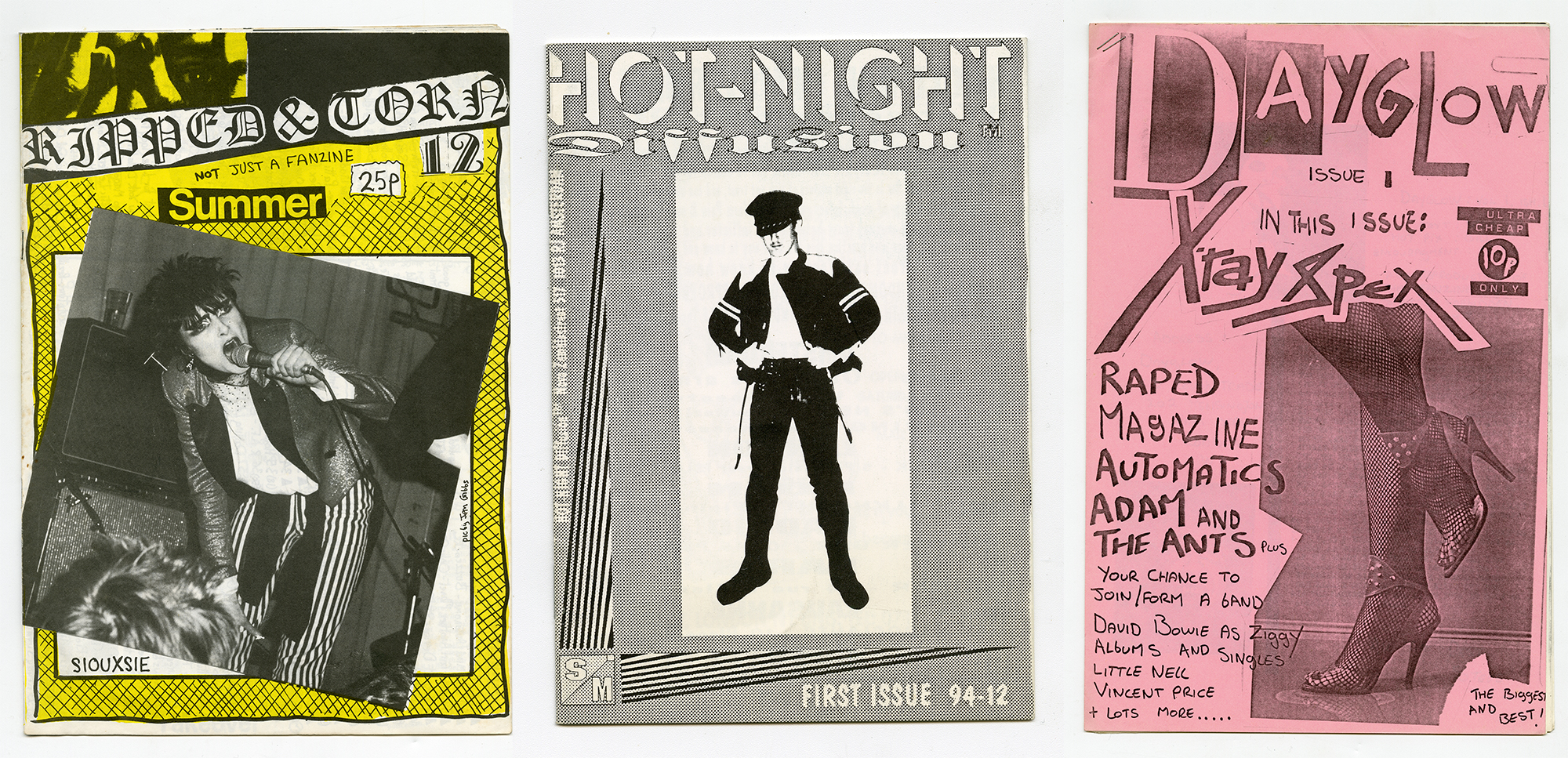

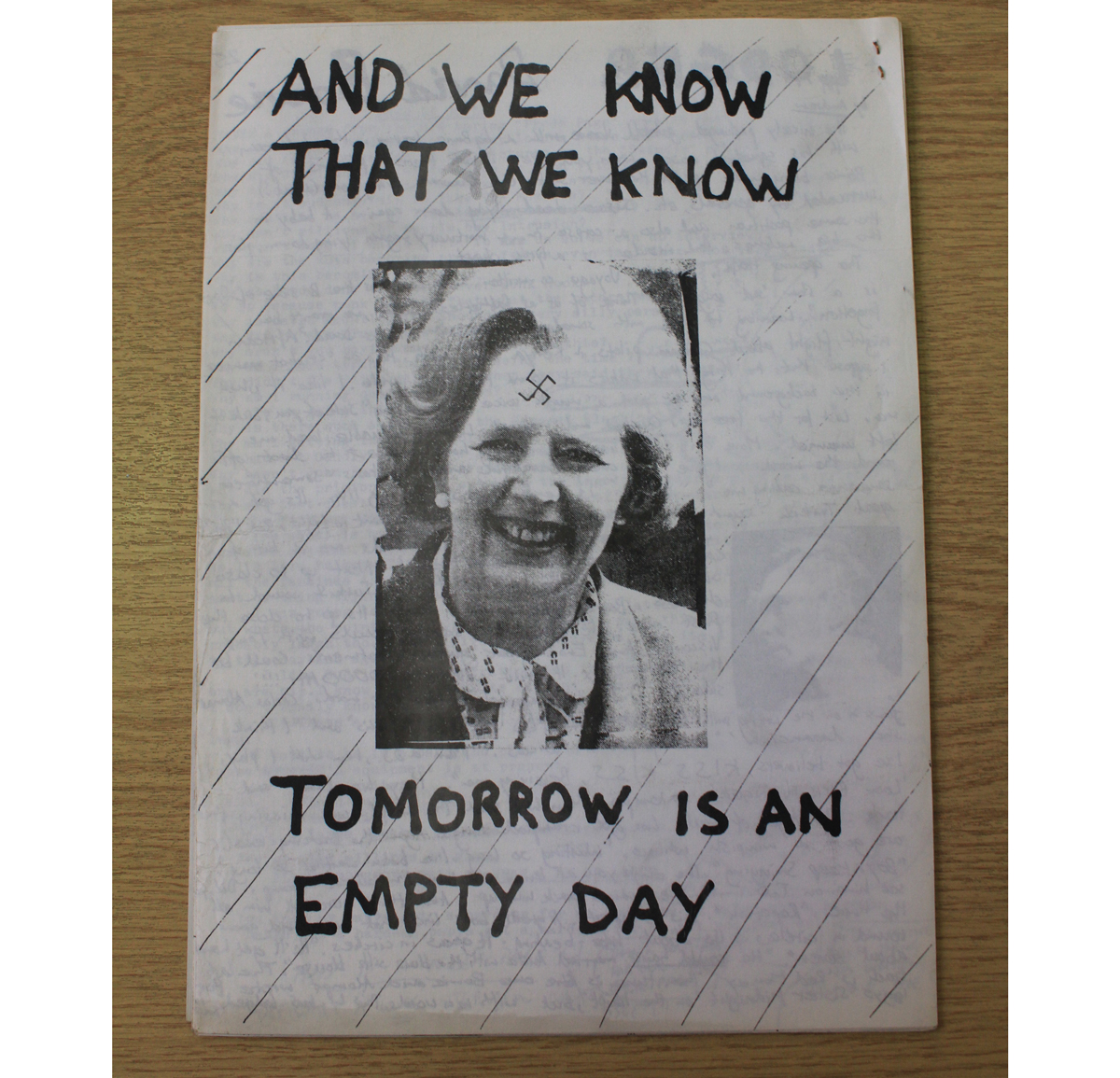

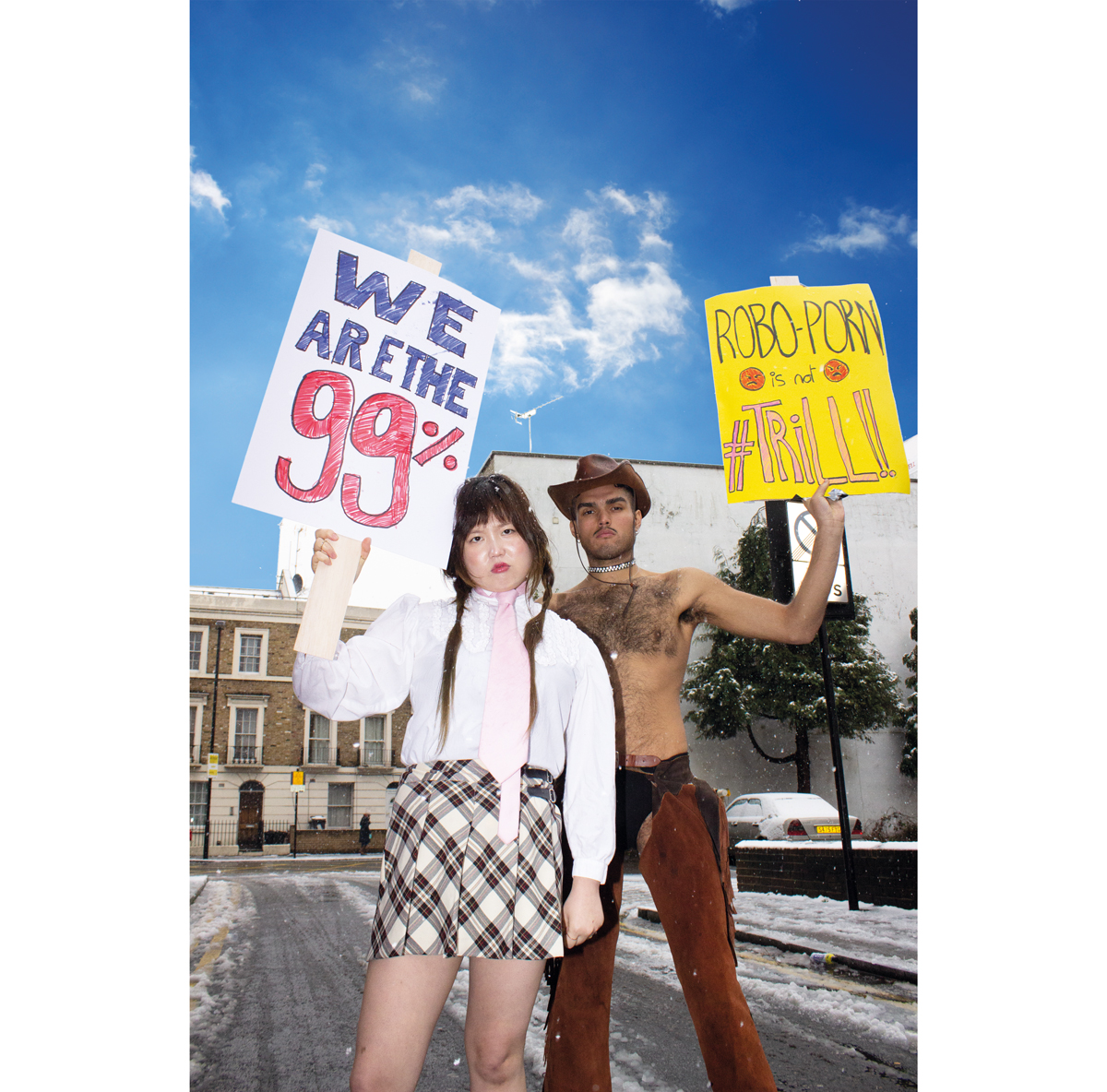

The aesthetic most of us associate with zines today – a visual chaos of cut-and-paste imagery, deliberately scrappy approaches to layout, maelstroms of numerous different typefaces, strange photographic crops, hand-scrawled notations – exploded in the 1970s with the birth of punk. Vitriol and ebullience alike were expressed in print as hastily put-together pages that indulge in their underground, countercultural status; the most famous of which are Sniffin' Glue, Mark Perry's zine from 1976 to 1977, and its US peer Search and Destroy, published by V Vale between 1977 and 1979.

The slapdash punk aesthetics of the 1970s made their way back to the forefront of counterculture in the 1990s – evidence of the adage of the two-decade pendulum swing of certain visual trends, referred to in the fashion industry as the '20-year rule'. As the riot grrrl scene took off, spearheaded by bands like Bikini Kill, Bratmobile, L7 and Babes in Toyland, the trends of their '70s forebears emerged again in zines like Jigsaw, Bikini Kill, (founded by the band of the same name), and Girl Germs.

Though we're nearing the end of the 20-year cycling back to the '90s, it's safe to say the decade's aesthetics are well and truly back. Consider pool sliders, Ellesse, Kappa, bumbags, bare midriffs. The Spice Girls have embarked on a reunion tour (sans-Posh), and in January, Bikini Kill also announced a reformation tour – the band's first live dates in 22 years. What this '90s resurgence has meant for the world of design is significant. Today, 'authenticity' is king, and that critical youth audience is increasingly hard for agencies and brands to reach. Most of us of working age have little comprehension of the intricacies of design memes, or the nuances of Snapchat. Thus, that which has always been 'cool' – counterculture, punk, anti-establishment – creeps back into the mainstream.

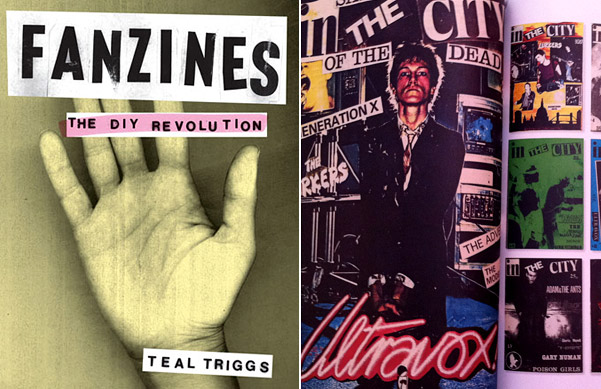

The impact of 'underground' zine culture on commercial branding is nothing new. As Teal Triggs points out in her 2010 book Fanzines, in the 1990s, "it seemed that everywhere you turned faux fanzines were being published by large multinational companies. The fanzine as a graphic form was co-opted – moving from an authentic, edgy, political underground into the world above as an item now imbued with commercial hipness." She cites brands such as the Body Shop, which published the zine Full Voice as part of its 1997 ad campaign, and the Wieden+Kennedy-masterminded U Don't Stop zine for Nike in 1998.

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Joy in imperfections

Rory Dewar leads the artist content creative team at Virgin EMI Records. Having studied music rather than design, he's largely self-taught and has always gravitated towards the DIY aesthetic of zines. "That's definitely my personal style if I'm given free rein," he says. "Since I wasn't trained as a designer, it was always about what you could do with what was around you. That's why my work has obscene amounts of texture and is scanned five times… I love the imperfections that creates, which you don't get from just sitting on Photoshop." Dewar's lack of formal education in design brings something different to his output, as he doesn't 'follow the rules' a traditional education instills.

Aside from its use in actual zines, that DIY aesthetic is most prominent in work for music clients. "There's less having to convince them than with more corporate design projects," says Dewar. What he finds interesting about the resurgence in zine-style aesthetics is that today, it's likely inspired by things we see online rather than physical artefacts. "When I was younger, I was always making my own zines and I loved that we had loads of issues of The Face lying around the house, but I really got into zine culture through Tumblr – a digital thing emulating a printed thing."

Part of the resurgence of physical formats, Dewar reckons, is down to social media trickery. "When you have graphic design with crisp edges perfectly aligned, Instagram and Facebook know they're digitally created and lessen the reach. But if I, say, printed off tour dates and photographed it, there's more engagement. That's dictating how some design is being created."

The new indie mag scene

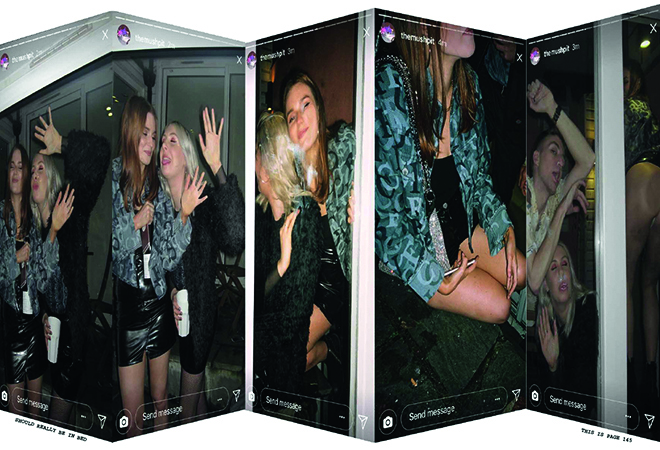

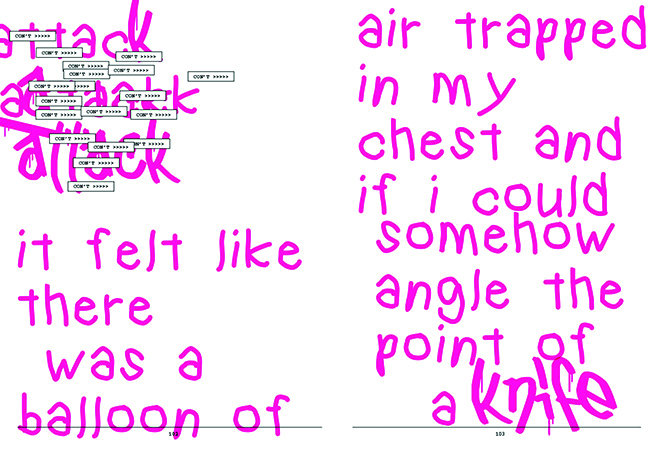

Where the 'zine' mindset associated with the punkish ideals of the '70s and '90s is most alive and well is in the current, apparently unstoppable rise of independent magazines. Where larger glossies and bigger publishing houses are struggling, independent mag-makers seem undeterred. Through their independence, magazines like Mushpit, Migrant Journal, Voortuin, PC Erotic and so many more share the freedoms zines thrived on: they can take not only the editorial content, direction and political leanings into their own hands, but their own design style. Chaos can reign again: why not use 10 different typefaces? Who cares if the illustrations are those usually relegated to the sort of thing found in the margins of school exercise books?

What's interesting is where that un-design style of design is appropriated by very much pro-designers: DIYas we know it has a new sheen. The production values of yore were simply the consequence of the means available to makers: Letraset, handwriting, photocopying and mimeograph were all readily accessible. Now, even the most basic computers can present far slicker outcomes.

"These days, the tools that people are using have become so sophisticated, literally anyone can make something that looks decent – InDesign shows you where to put things for equal spacing and so on," says Steve Watson, founder of magazine subscription service Stack. The ease of making something perfect, he suggests, is partly behind a number of publications emerging that are "a reaction against that; they don't want the perfect evenly spaced thing. They're trying to evoke some friction."

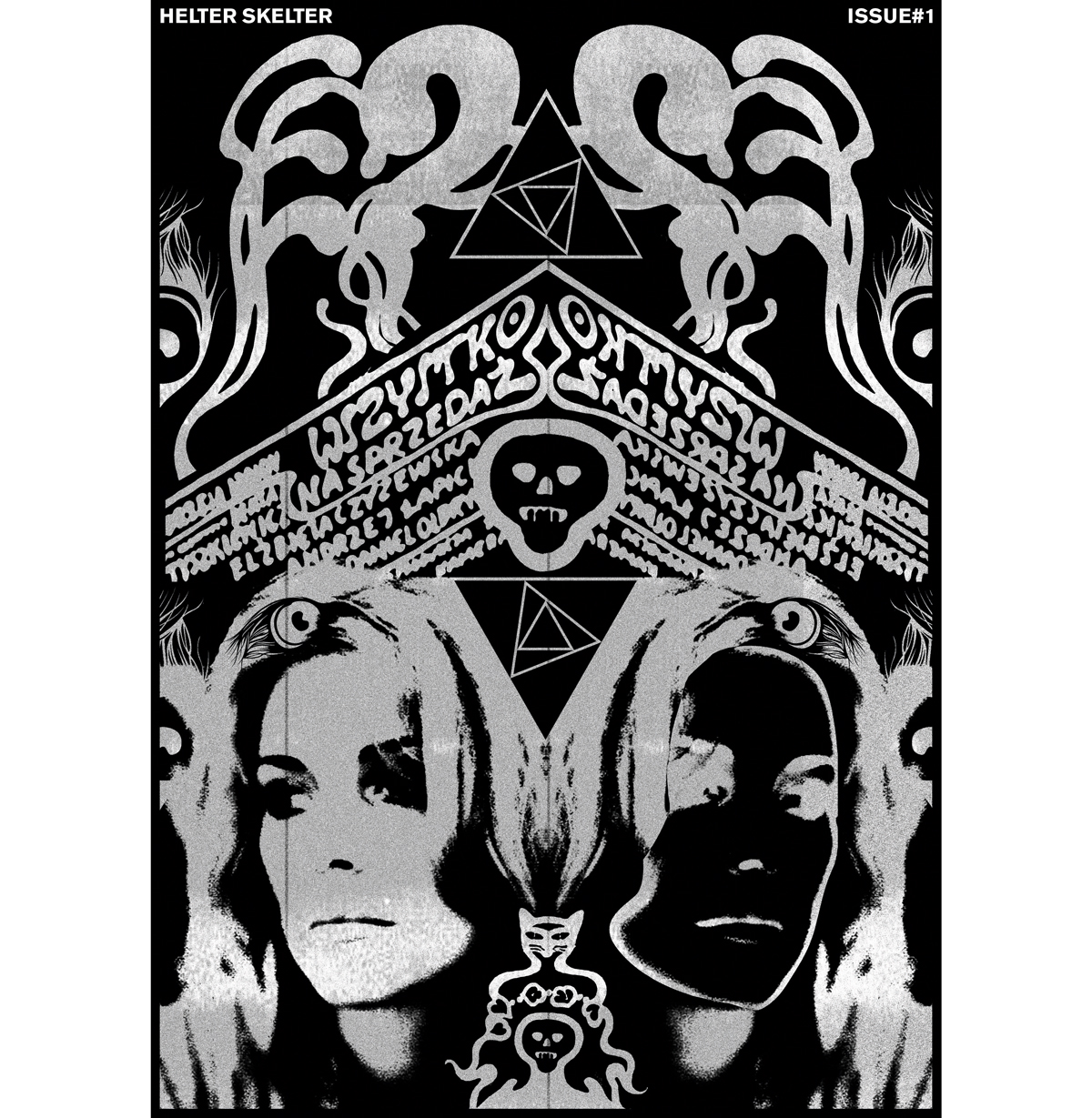

Where psychedelia meets punk

The beauty of zine style is that it can really mean anything that draws together numerous threads to create something visually exciting, and which pushes a message. As such, it's an approach that very much suits graphic designer and illustrator Luke Insect, who describes himself as "a bit of a magpie," inspired by the "original counterculture" magazines he inherited from his dad, such as Oz and International Times.

"I've always been into montage and cut and paste," he says, pointing out that while psychedelic mags ostensibly had a vastly different message to their punk descendants, the aesthetic and attitude isn't all that dissimilar. "'Peace and Love' is obviously very different to 'fuck Thatcher', but if you flick through Oz magazine, there's a lot of black and white editorial, anti-establishment stuff, weird little ads, cutups, badly chopped photos. Even in psychedelic zines, that cut-and-paste aesthetic is there, alongside the cheap printing and the technicolour, otherworldly covers."

He's excited by the resurgence in zines as a platform for creatives to get their work out into the world. "When we were setting up [illustration studio] Insect in the '90s, it was more about coffee table books. A couple of years ago we saw the rise of things like Risograph zines; suddenly we could have all these amazing things that cost £8 rather than spending £40 on a book."

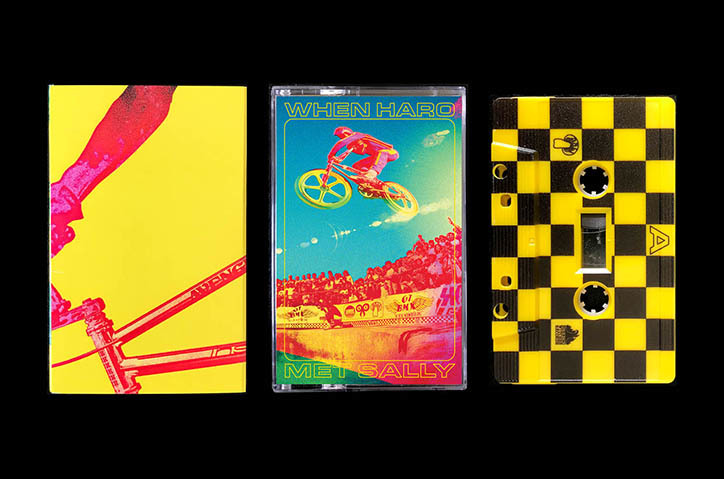

A callback to the early '80s

Insect is working on a zine for electronic music artist Damon Baxter [aka Deadly Avenger], which references post-punk and new wave zines of the late '70s. The piece is a follow-up to last year's When Haro Met Sally, a music and art project that comprised posters, cassettes and a record that boasted an aesthetic drawing on "California, hazy skate culture zines," says Insect. The new piece will be "colder and more UK-focused," with an insert in the form of a "fanzine that looks like it's from 1981."

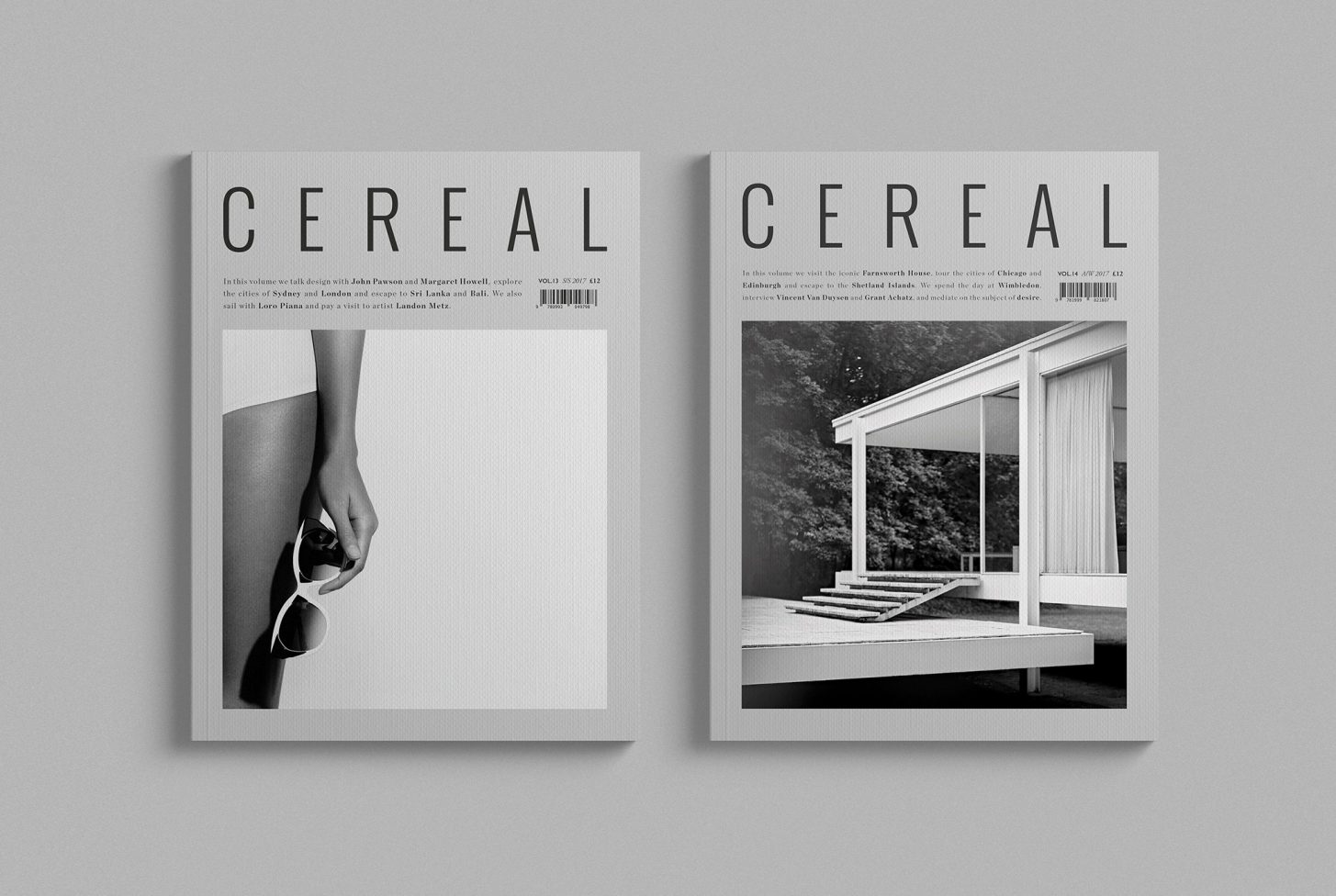

Aside from the modern availability of more sophisticated, digital production means, Watson reckons the move towards a more obtuse, self-aware and ultimately fun style is also a reaction to the wave of calm, polished magazines that arrived with the likes of Kinfolk and Cereal in the early 2010s. While these were imbued with a sleek sense of pared-back sophistication, a certain maximalism and devil-may-care attitude to both tone of voice and visual language now abounds.

"People are trying to get away from the very minimalist, controlled, perfect independent mag aesthetic," he says. "You see these currents with everything, so maybe that's what people like Mushpit are responding to. That's how trends, and then counter trends, emerge. Now, people don't want that tidiness – they want to introduce more friction and craziness."

Dewar agrees: "There was a period when everything on social was perfect and Photoshopped. Now we want to see unfiltered messiness – the shit food people eat as well as the nice stuff. We want to know that people are working hard, and doing things themselves when it comes to artwork."

Not only are today's designers looking to printed zine cultures, but to a certain, very '90s-looking desktop publishing style: lurid colours, layouts peppered with clip-art-like graphics, and multifarious system typefaces. "We're seeing people deliberately making stuff that looks like it was created on Windows 98 or something, and people are doing that very well," says Watson. "That style is having a bit of a moment."

Definition of freedom

Indeed, the word 'zine' has long transcended its original signifier as a piece of strictly printed matter. For LA-based designer and art director Sam Jayne, the aesthetic is "about freedom within a defined space," he says. "That space could be defined by the limitations in printing, software, technical knowledge, colour, etc, and then freedom to communicate your thoughts in whatever way you, the producer, chooses."

One of the main exponents cited as embodying this 'crazier' aesthetic is Mushpit, which is art directed by Ben Freeman. Freeman, who worked at Vice in its early days and is the founder and creative director of Ditto Press (among a ludicrous amount of other projects), published and designed his first zine when he was aged just 12 in 1990.

Last year, he collaborated with editor Iris Luz on a new publication, PC Erotic. Billed as "the future of sex you never wanted", the magazine explores the confluence of sexuality and technology. It's playful, often hilarious, and somehow rather beautiful – quite a feat considering Freeman and Luz went for a look that directly draws on 2000s and late '90s lads' mags like Nuts. Like many DIY zines from the era, as well as their commercial counterparts, the aesthetic is based around any and every font and piece of clip art you can find on the software you have.

Despite the incredibly sophisticated tools we have at our disposal to imitate a time when we didn't, such magazines align perfectly with 'traditional' zine culture, in that they exist purely because their creators wanted to put a message out into the world that wasn't there before. "There often isn't a commercial background, they don't exist for the person making them to make money, but because there's a set of ideas they want to communicate," says Watson.

'Selling out'

While the zine design style is undoubtedly one that best lends itself to cultural clients – namely music – Insect points out that aesthetics birthed in counterculture – sound, fashion and editorial – so often "drip feed" as "watered down" versions into more commercial applications, such as advertising campaigns or high-street brand T-shirts.

The notion of 'zines' however, is not just a graphic language or aesthetic, but an attitude. Zines are about self-expression, and authenticity of voice – an opportunity to speak openly and frankly about issues that may otherwise be muted or deemed too thorny, such as politics or identity or non-conforming sexuality. As such, zines themselves are analogous to a certain youth cultural spirit: they enable empowerment through dissemination of information.

The fact that zines were often created, edited, written and designed by one person is crucial: there's no one to answer to, opening the floodgates for experimentation away from hovering design directors and editorial censorship. It's that aspect, perhaps, that's lost in zine style's commercial manifestations, where such a voice becomes simply a way to market a brand or product.

If a zine's 'authenticity' lies in, as Triggs puts it, an authorial voice "where the personal is political and not beholden to global corporations," then it's interesting to consider that commercial brands or publications (which must pay heed to advertisers, a broad readership, and so on) aping zine style are inherently forgoing these tenets. Zine style, we could say, has since been mimicked to the effect of that ultimate antithesis to all things punk and youth culture – 'selling out'.

This article was originally published in issue 292 of Computer Arts, the world's best-selling design magazine. Buy issue 292 or subscribe to Computer Arts.

Read more:

Emily Gosling is a freelance art and design journalist currently writing for titles including Creative Review, Eye on Design, Creative Boom and People of Print. She’s previously worked at Elephant magazine, It’s Nice That and Design Week, and was editor of Type Notes magazine. Her book Creative Minds Don’t Think Alike was published by Ilex Press in 2018, and she also plays bass as one-quarter of the eight-titted beast, Superstation Twatville.