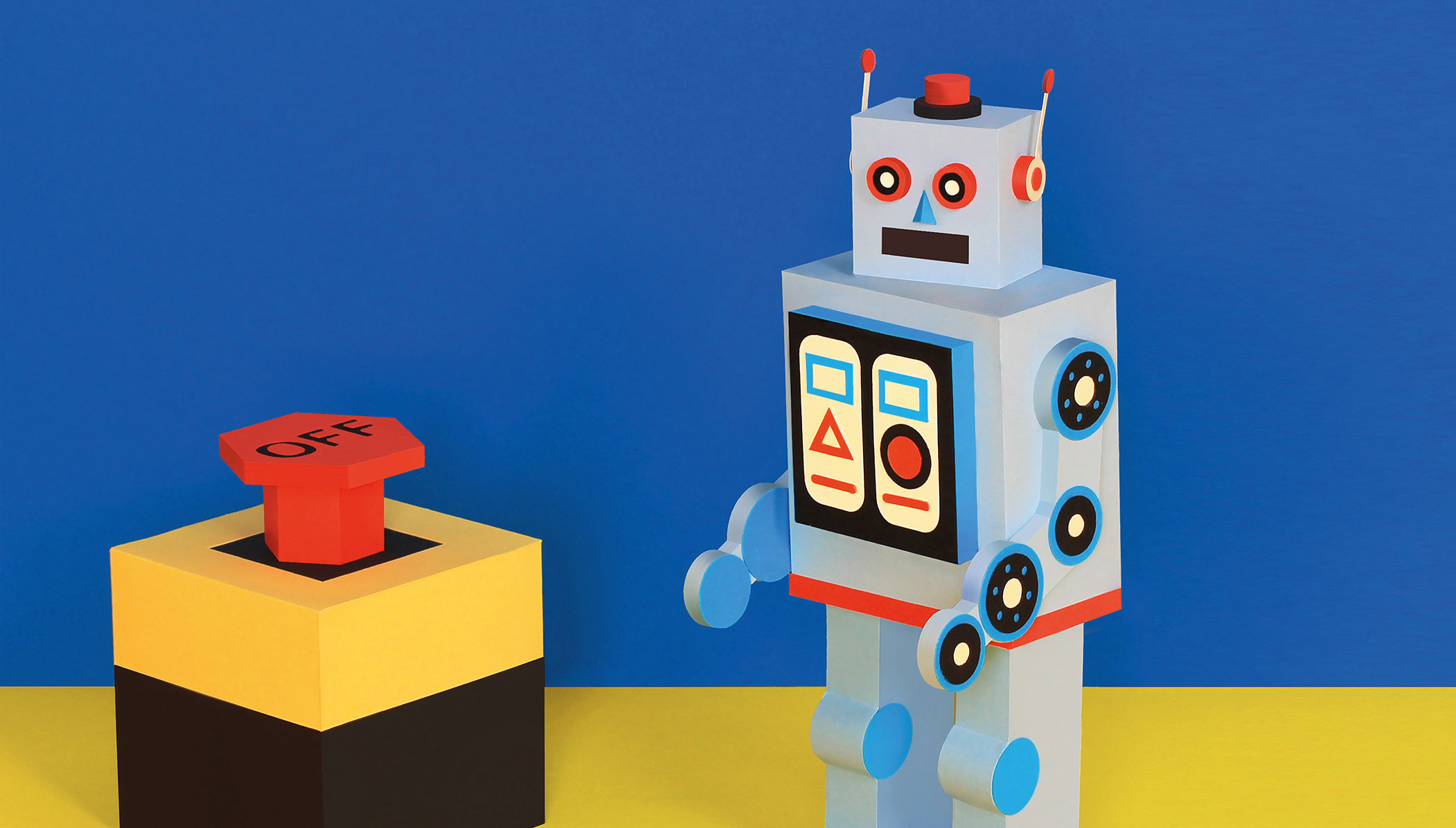

How to create a papercraft robot

Discover how to create paper models with absolute precision.

Having only graduated last summer, I’m still pretty new to the world of freelance illustration. My style and process, however, are things that I’ve been developing for quite some time now. I dabbled with paper art during my A-levels and Art Foundation, but university was where I truly fell in love with the material.

Initially, I cut everything using a scalpel and produced a lot of layered, two-dimensional illustration. This process was extremely time-consuming and the end result always looked very handmade. As I progressed, I started working with a laser cutter – this gave me the advantages of speed and precision but it burned the edges of my paper.

Now, I cut my papers using a plotter. The plotter also facilitates speed and precision but, instead of a laser, it cuts with a blade, which eliminates the unwanted burn.

01. Start planning

The first stage of every project is planning; in this stage I make lots of rough sketches and notes. However, paper (like any material) has properties that sometimes pose constraints. These constrains don’t always become apparent until I begin making my creations; so I keep my initial designs loose, and leave space for the paper to make some of the decisions.

02. Gather inspiration

Once I have a basic idea of what I want to create, the visual research begins. I usually start by looking on Behance, Instagram and Pinterest. That being said, I don’t like to get all of my inspiration from other illustrators and paper artists. Though I am inspired by and admire their work, ultimately I want to create something different, so I like to look for other sources of inspiration too, for example using architecture, fashion and still-life photography.

I collect all of this research in a file until a style or theme begins to emerge. I then print off the relevant images and put them up on the wall in front of my table, which is where they stay until all of the models for that project are complete.

03. Choose a colour theme

In this stage, I also put together a colour palette. I love the colours used in Toilet Paper Magazine and in the work of Jessica Walsh or Aleksandra Kingo. Their use of bold tones and unexpected combinations is very striking and as a result, their work often features heavily on the inspiration walls for many of my projects.

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

04. Buy your paper

Once I’ve decided upon a colour palette I then buy the papers. For personal projects, 210gsm multipack card usually works fine, but it does limit my colour options.

When I need something more specific, I order it from Arjowiggins, which has a great selection, and I can order as little as one sheet at a time. This is useful for small scale projects or one-off models.

05. Make a model

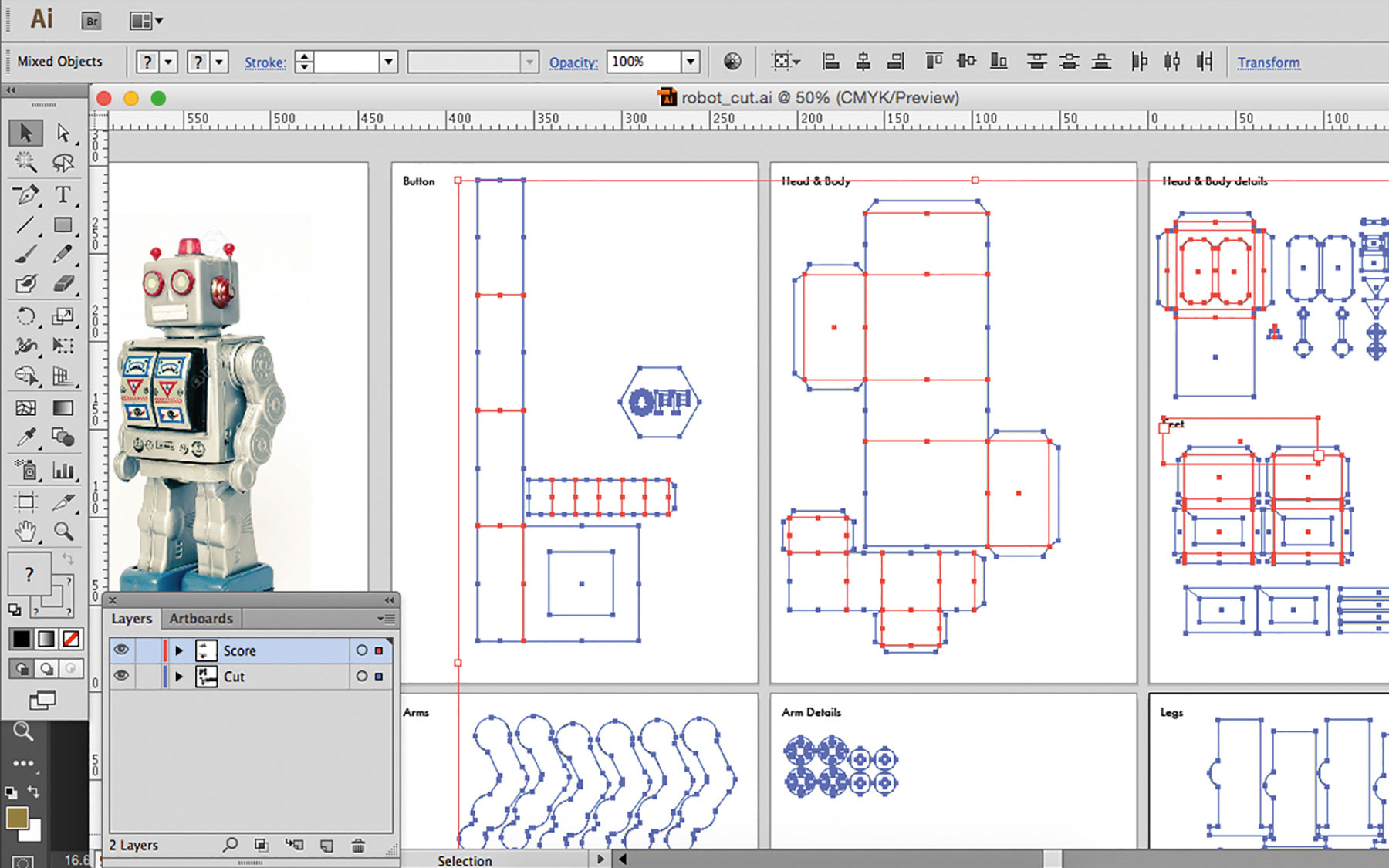

With my colour palettes chosen, illustrations planned and paper selected, I take to Illustrator CC. The artwork is made up of paths split between two layers – one layer has the paths I want to cut out, and the second has the paths to score/fold.

Since most of my work is three-dimensional, I begin by designing nets. In my mind, I visualise how the net will fit together and then artwork that vision using the paths and layers described.

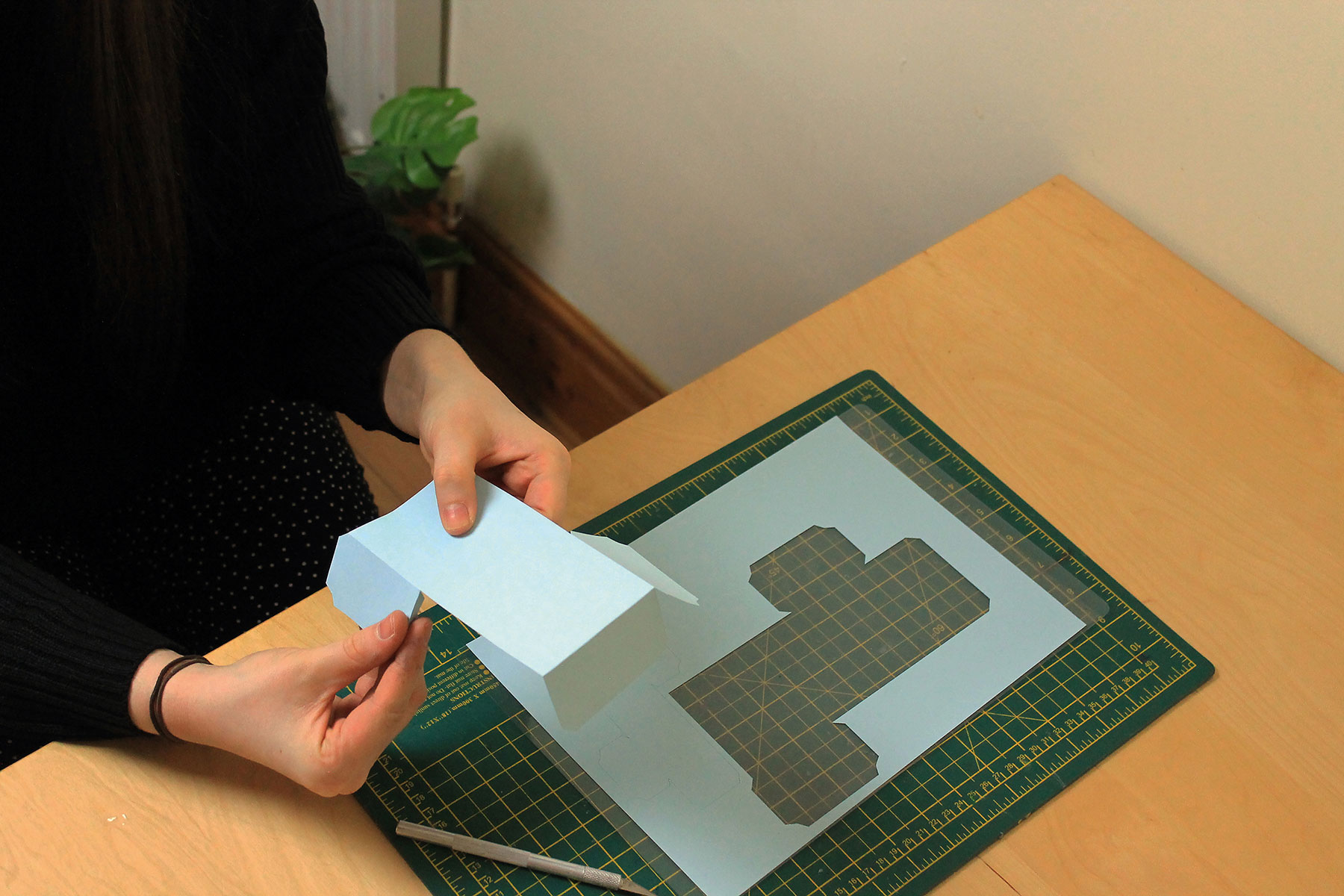

Once I have the basic design, I cut out and test it, but the first draft is rarely ever perfect. So then, I use a process of trial and error until the net is exactly how I want it to be. For this part of the process, I use cheap card and work on a very small scale to limit waste.

Once I’m happy with the net, I can then scale it up or down. This stage can be relatively quick and easy or very long and challenging. It depends on the project, the scale and the level of complexity.

06. Work out the details

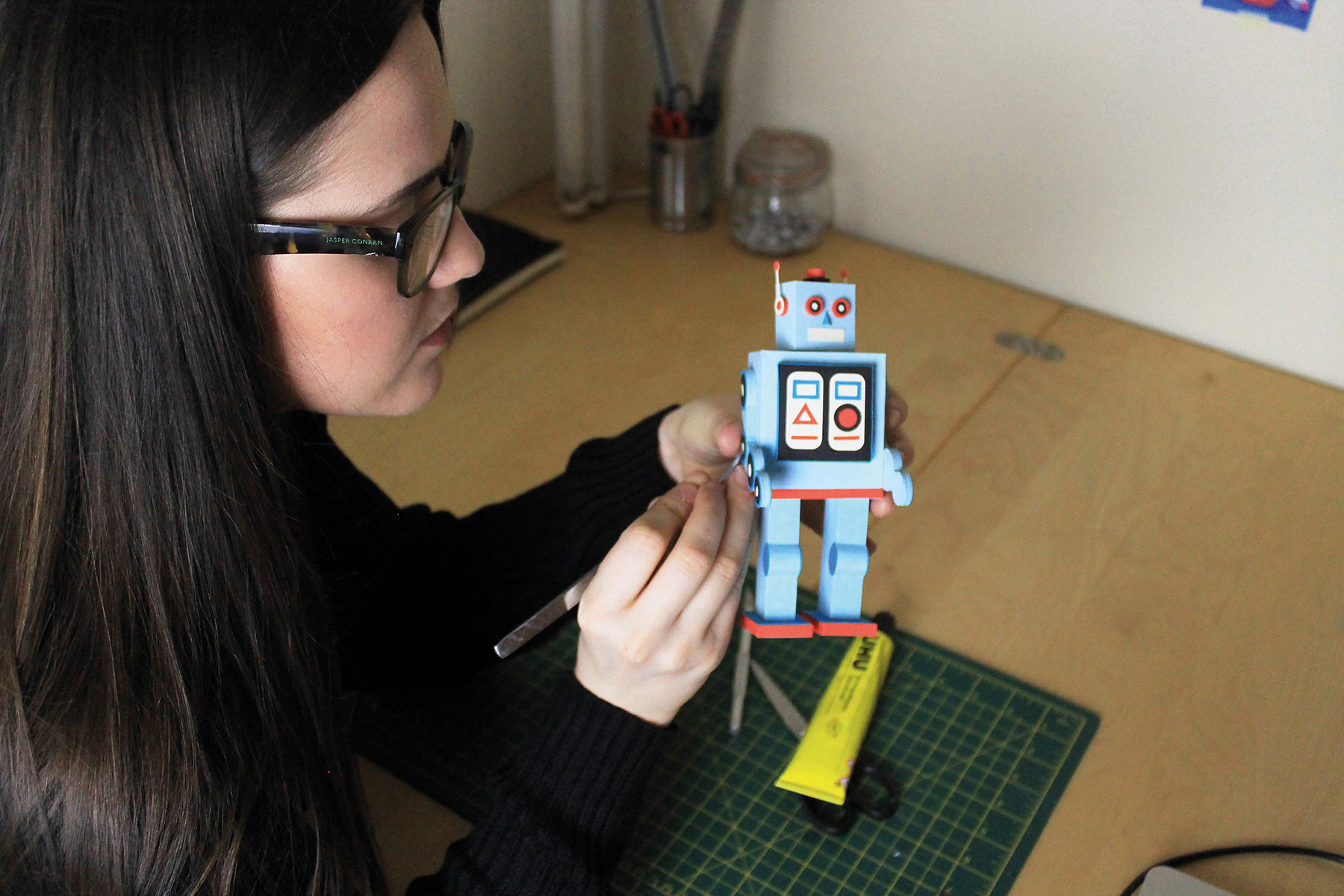

Now the detailing. I take the faces of the net and work out which details will go onto them. Then I cut the details out and stick them to the unassembled net using all-purpose glue. Finally, I stick the pieces of the net together to complete the model.

People assume that cutting is the trickiest part of the paper process, but for me gluing requires the real patience. The glue is extremely runny when it first comes out of the tube so I have to remain focused to ensure it doesn’t get on to any exposed sections of the model.

Once it’s dry, the glue leaves an unwanted shiny stain on the paper so if it does run, I have to discard and re-cut all of the affected pieces. This is both time-consuming and wasteful, which explains why precision is so crucial at this stage.

07. Turn physical to digital

A lot of the time, the digital elements of my process can take just as long as the physical ones, and if I’m working on an animation, then sometimes they take even longer.

Photographing the models is the first step towards turning my models into digital artwork. Though I am keen to work with more photographers in the future, at the moment, I shoot most of the models myself. To do this, I use soft box lighting, and a camera set up on a tripod. Then, to complete the process, I edit the images in Photoshop.

This article originally appeared in issue 280 of Computer Arts, the world's leading design magazine. Buy issue 280 or subscribe here.

Read more: