Why designers fail - and how to embrace failure

Victor Lombardi explains what experience designers can learn from past failures.

- This is an edited excerpt from Chapter 1 of Why We Fail, published by Rosenfeld Media. Use the discount code creativebloq to buy the book at a 20 per cent discount here

"Ultimately, we are deluding ourselves if we think that the products that we design are the 'things' that we sell, rather than the individual, social and cultural experience that they engender, and the value and impact that they have. Design that ignores this is not worthy of the name."

- Bill Buxton, computer scientist, designer, and a pioneer of the human–computer interaction field

Why I failed

The year was 2000 and I was employed at a prestigious digital design agency working with a financial information company to create a new website that would revolutionize the research process for institutional investors, the people who manage investments for large companies and municipalities

"Make it like a Bloomberg Terminal," is how the client summed it up. My team of designers and programmers winced at his suggestion because we considered the Bloomberg Terminal a powerful but ugly and difficult-to-learn interface design from the dark ages of text-based computers (Figure 1.1). We instead pushed him in the direction of beautiful charts and graphs, software agents that personalized information, and conventional web navigation that would be familiar to his clients.

Our client hadn't actually done any research with his customers to understand if they would like his ideas. And neither had we. He was leaning on his expertise in managing similar products and we were leaning on our experience having designed similar products, but neither of us had validated these particular ideas with these particular customers. At the time, the methods we had for validating our ideas were not compellingly useful, and perhaps my team and the client implicitly understood this. We made minimal effort to conduct research with the client's customers, and he denied us access to them.

With each stage of the project the design and technology accumulated more flaws. When the client decided the team was wrong for the job, another team at my agency replaced us. After more missteps the client's upper management replaced their team. Eventually the whole project was canceled; the client's company decided to use off-the-shelf software instead, which was never a success with its customers. In the end the project was a failure, all too common in the early days of the web.

The blame game

Ouch. I was a young designer and had never experienced a big failure at work. I felt terrible. No one at our agency wanted to focus on the failures and take time to discuss them, so the team never understood why we failed. Without a good explanation and without something tangible I could do to improve, I sometimes felt depressed and I lost confidence in my skills. Sometimes I became defensive and blamed the 'dumb client'.

But I saw that things around me were even worse: clients were firing agencies after as little as a month or clients were suing agencies. Some of the mistakes agencies were making were to be expected. The Internet represented a new world of design and technology that changed on a daily basis. Everyone was learning and experimenting; there were no experts.

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

Since the time of that first early failure, I've contributed to or directly managed over 40 internet and software projects, some as a designer and some as a product manager. There have been other failures, and even when I understand why I failed it still takes an emotional toll. In spite of my own failures, you'll see as you read this book that I'm often a harsh critic of my peers' work. I don't criticize because I think leading a design project from start to finish is easy. It's not. It's hard work. I criticize the outcomes I see because it's hard work and because failure is still too common. I want all of us to get it right more often, with less of the emotional toll of failure. I hope by reading this book and applying the lessons learned, avoiding failure will be easier for you and those you work with.

I failed mostly because I didn't have the right methods to discover which of our ideas would give customers an experience they wanted. Since then, those methods have improved significantly.

Why this stuff is really important

I see the trend of our work going beyond the ubiquitous convenience it is today and becoming a vital part of the infrastructure supporting life in the 21st century. Currently most of our work complements or enhances life; people don't rely on it as essential yet. An updated status on Facebook, an e-mail to a friend, accessing information on websites... if all this were turned off tomorrow people would feel inconvenienced, but they could find work-arounds for all of it.

But that's changing rapidly. I now make appointments with my doctor online, and the doctor transmits my prescription for medicine directly to my pharmacist online (Figure 1.2). I pay the doctor, the pharmacist, and the health insurance online. As people become accustomed to this way of working - and as service providers become accustomed to the efficiency, accuracy, and cost savings - the old ways will gradually be discontinued. Increasingly, we will rely on digital products and services for everyday matters of life and death.

We are each the product of our experience. The things we do, the places we go, the people we meet, and the things we use all influence who we are. Over time, as we interact with more and more technology to live our lives, we will spend more of our time looking at screens, and the quality of the design of this technology will have ever greater influence on the quality of our lives.

Why we learn from failure

Instead of studying failures, can't we just study successes and then repeat whatever led to those successes? Yes, this is a good tactic in very simple situations, such as learning how to tie your shoes. There's not much to be gained by looking at how many ways it's possible to tie your shoes incorrectly. If you fail, nothing terrible happens.

Any industry that's important, complex, and dynamic takes the time to examine failures. Aviation, medicine, and manufacturing are three fields that have taught us an enormous number of lessons by studying failures.

Here's a good example. During World War II a mathematician in the United States named Abraham Wald worked on the problem of deciding where to add additional armor to B-29 bomber planes to keep them from getting shot down. Looking at planes that had successfully returned from flying missions, he determined statistically where the bullets had hit the planes and plotted the locations, as represented schematically in Figure 1.3.

The initial reaction to this data might be, "We need to add additional armor to the dark areas because that's where the bullets are hitting the planes." Wald's insight was that the planes with bullet holes in the dark areas returned successfully, so perhaps the planes that did not return were shot down because they had bullet holes in the light areas. His recommendation was to add armor to the light areas instead.

As a statistician, Wald would naturally want to make a decision based on a random sample of all planes, but he didn't have access to the planes that were shot down. He understood the limitation of his sample and adjusted for it. He successfully dodged survivorship bias, the mistake of learning only from the survivors of some process.

Survivorship bias happens all the time. Witness the marketing hype in our industry that, devoid of research, hails every new method and technology as the fix for people's business or personal needs. It seems easier to research and analyze companies and products that currently exist instead of searching for information on companies and products that have perished. Doing so can lead us to believe that the survivors have some special quality that helps them survive, when it's possible they were just lucky (Figure 1.4).

The lesson here is very simple: to increase your chances of success and lower your chances of failure, you need to carefully examine cases of both success and failure.

Why experience failure is different

So we know why studying failure is important, but do we really need another book on failed products? Yes we do, because previous books were about design rather than experience.

To help illustrate the difference, I'll group the many design-related failures into three broad categories:

- Engineering failure: The product physically fails to function as designed.

- Design failure: The product physically works, but is so badly designed people can't use it.

- Experience failure: The product physically works and people can use it, but using it is an undesirable experience.

For engineering failure, we have great studies of how and why things fail in physical ways, most notably Henry Petroski's studies of buildings, bridges, and pyramids, as in his book Success through Failure: The Paradox of Design. But studying a bridge that failed is worlds apart from studying a failed website. When people use bridges, they don't directly interact with them the same way they interact with digital products. For example, a sleeping passenger in a car can pass over a bridge without even knowing it, whereas people actively and directly interact with digital products (Figure 1.5). I've never heard of a bridge that was torn down and replaced because people didn't like it much. But in this age of plentiful digital products, people have enough options to be selective about what they use.

In the second case, design failure, the product physically works but its design makes it too hard to use. We used to call this 'human error' but the more common term in the fields of ergonomics and human factors is now 'design-induced error', which moves the blame from the people using the product to the people who designed it. Whenever you're using any kind of computer and feel confused about how to use it correctly, you're experiencing design-induced error. Many of us are old enough to remember trying in vain to set the digital clock on our VCRs. This is a classic example of a design-induced problem (Figure 1.6).

Having a product break and feeling confused by a design are definitely things people still experience, but interactive digital products are more sophisticated now. They do more than just perform simple functions like recording a TV show at a particular time. They connect us socially, they allow us to shop and conduct business from home, and they smooth a million transactions from navigating a car to finding a book at the library. Mere usability is a low bar for these products to clear; they now aim much higher, engaging our higher-level functions and sometimes even engaging us emotionally.

While the concept of design-induced error is a useful subset of failure I'll look at in this book, experience failure comprises much more.

In this book I will talk about design - the appearance and behavior of a product - separately from the experience - people's thoughts, feelings, and actions while using the product. I illustrate this distinction explicitly in Chapter 8 of my book with the case of Nokia's Symbian S60 mobile phone operating system. The Symbian-based phones had a long list of features and high-performance specifications that sounded great on paper, but the iPhone and Android phones offered a more pleasing experience, despite having far fewer features. With the first iPhone you couldn't even spell-check your e-mail or customize your ringtone, and yet it sold very well. Consumer electronics have now reached a performance threshold where more features and performance offer diminishing returns unless the design helps people have a good experience.

One observer has called this "the death of the spec", meaning the list of specifications is no longer as important as the experience. This phrase was coined as a result of 'Antennagate', the controversy over the signal reception of Apple's iPhone 4 in July 2010. Consumer Reports magazine evaluated the phone and found that holding it a certain way would significantly reduce the signal strength, a potentially fatal flaw for a mobile phone. The magazine, usually content to simply publish ratings and move on, went further and issued several news updates, even calling on Apple to fix the problem (Figure 1.7).

You might assume with all the publicity about a fundamental flaw in the iPhone 4 that sales would plummet. For the fiscal quarter ending September 25, 2010, Apple sold 14.1 million iPhones, which was 91 per cent more iPhones than the same quarter from the previous year. Apparently people who wanted the iPhone 4 decided to buy it against the advice of independent product experts. This massive contrast between the publicity of the defect and the record sales numbers served to highlight the death of the spec of interactive digital products.

Marco Arment, a software developer and technology writer, offered this explanation for the situation: "For [Consumer Reports'] ratings to be useful to my purchase, their priorities and criteria need to approximately match mine. This is easy for most of the products they review: [...] an air conditioner that uses less energy for the same cooling is better than a less efficient model. You can assign numbers and scores to factors like these.

"Smartphones have too many subjective criteria, and even the measurable stats don't always yield a definite answer on what's better. If you want a huge screen, you'll get a huge phone, so is a larger screen size a good thing or not? Fast 4G network access kills battery life, so is 4G a good feature for you? These all depend on your priorities.

"A product as complex and multifaceted as a modern smartphone is beyond Consumer Reports' ability to rate in a way that's useful to most buyers."

Subjective is the word that stands out for me here. While the qualities of a design can be objectively described on a list of specifications, the qualities of people's experience - their thoughts and feelings about a complex, multifaceted product - are subjective.

And that's one thing about designing digital products these days that is different and, I think, trickier. We just don't know if they work or not until we evaluate the subjective experience of the people using them. Sure, we can check if the products function correctly and ask independent experts to review them. But the products we're now making are experiential products, and only the people experiencing them know if they are ultimately successful or not (Figure 1.8).

Why design equals experience

To fully understand the failures cited in my book, I describe both the product design and the outcome of that design - the experience. Ultimately it is in the experience that these products fail, but by presenting both the design and the experience I hope to illuminate the difference and help you completely appreciate the lessons learned.

Even though I've been working in the 'experience design' industry for years, this design/experience dichotomy hasn't been easy for me to arrive at. Because we so often use the word 'experience' to describe the design, it takes some conceptual backflips to think about a person's experience apart from the product.

To help you see the difference between design and experience here are two automotive examples. I like taking examples from the automotive world because most people are familiar with cars. Figure 1.9 is a video describing the design of a new concept car. The reporter discusses the styling, the price, and the business issues at the automaker, but not the experience of what it's like to drive the vehicle. This is only a concept vehicle and the reporter didn't have access to a working prototype.

Figure 1.9: In this video about a Lamborghini concept vehicle, the reporter discusses the design but not the experience

Contrast that with the video of an off-road rally car driver taking a passenger for a short ride (Figure 1.10). We don't know where they are, who they are, or how fast they're going. We don't know anything about the design of the car other than the little we can see in the blurry video. But we know the woman in the passenger seat is ecstatic, smiling throughout the entire four-minute ride, laughing and uttering curses as she's bumped and tossed around. That's experience.

Figure 1.10: You can appreciate her experience of riding in a rally car without knowing anything about the design of the car

Here's a parallel example relevant to software. Figure 1.11 is a video I made highlighting an interesting design aspect of Microsoft Office 2007. It's all about design and not at all about experience.

Figure 1.11: The design (but not the experience) of the ribbon in Microsoft Office.

Next is a video compilation of disabled people interacting with Drupal websites (Figure 1.12). We can't tell much about the design of the websites from the video, but we get to see people's reactions as they use the sites and later reflect on the experience.

Figure 1.12: People's experiences with Drupal websites

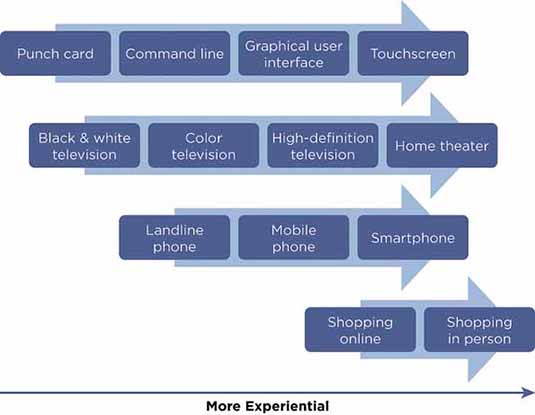

This focus on experience isn't new, but only recently has it started to become more widespread as a concept. The seminal work on experience as an economic force is The Experience Economy by Joseph Pine II and James H Gilmore, first published in 1999. They observed that "companies stage an experience whenever they engage customers, connecting with them in a personal, memorable way." They argue that experiences are an economic force just like commodities, goods, and services, which can be intentionally produced, consumed, and measured.

One reason for isolating experiences is that they are profitable. For example, Pine and Gilmore show how the profit margin for coffee increases along a value chain. The raw beans to make a cup of coffee (a commodity) cost 1 or 2 cents, but when a manufacturer roasts, grinds, and packages the coffee for sale (a good) the price to a consumer increases to as much as 25 cents. A brewed cup of coffee at a quick service restaurant (a service) can increase the value to between 50 cents and a dollar. Starbucks deliberately aims for a highly engaging experience - by preparing special beverages and serving them in an environment enhanced with interior design, music, and Internet access - and receives $2 to $5 for a cup of coffee.

Compared with commodities, goods, and services, the consumer price index shows that people are paying increasingly more for experiences. Experiences also show a faster rate of growth when contributing to both employment and gross domestic product (GDP).

As competition in various industries increases, companies sometimes try to move up this value chain, turning their commodities, goods, and services into experiences and seeking higher profit margins. For example,

"Glimcher Realty Trust, which owns and manages shopping malls, is experimenting with making them Internet-proof. The company concedes that if shoppers can buy something online, they will. So it is trying to fill one of its malls, in Scottsdale, Ariz., with businesses that do more than sell stuff.

"There are still clothing-only retailers at the mall, Scottsdale Quarter, but more than half of the stores offer dining or some other experience that cannot be easily replicated on the Web. That has glimcher executives taking some unconventional approaches to finding suitable tenants—like testing out laser salons, getting hairstyling lessons, and watching movies in a theater that serves food.

"'It's retail Darwinism,' Mr. Glimcher said."

Nathan Shedroff's book Experience Design is the seminal introduction to the design of digital, experiential products. First published in 2001, the touchstone work ranges broadly from interaction design to designing for the senses. Here's how Shedroff describes the state of the field:

"The design of experiences isn't any newer than the recognition of experiences. As an approach, though, experience Design is still in its infancy. Simultaneously having no history (since it has, still, only recently been defined), and the longest history (since it is the culmination of many, ancient disciplines), experience Design has become newly recognized and named. However, it is really the combination of many previous disciplines; but never before have these disciplines been so interrelated, nor have the possibilities for integrating them into whole solutions been so great."

Both The Experience Economy and Experience Design argue that a product or service is designed, sold, and used differently than an experience.

One reason we can turn our attention to our audience's experience is that we're less challenged to design technology to satisfy basic functions. Before, we had to work hard to design interfaces that could compensate for performance shortcomings, whereas now we sometimes have more computing speed, communications bandwidth, and storage than we generally require. The experiential threshold is crossed when technology reaches a point of sophistication where product design can engage people's emotions.

A recent example is the portable music player. In the 1980s portable cassette players like the Walkman let people take their music with them, but the devices themselves didn't engage their emotions (Figure 1.13).

In the 2000s digital music players transformed that experience by storing people's entire music collection in their pockets and adding interactive screens, especially touchscreens (Figure 1.14). Suddenly the range of interactions increased dramatically. Sliding a finger on a screen allows an infinite number of input possibilities, and the devices can use graphics and sound to communicate back to the user, becoming so much more than just music players.

This concept of the experiential threshold is gradually permeating the technology media. For example when Microsoft released its Windows Surface tablets in June 2012, Darren Murph at Engadget wrote:

"Microsoft's playing coy when it comes to both CPU speed and available memory. Not unlike Apple and its iPad, actually. We're guessing that the company will try to push the user experience instead of focusing on pure specifications, and it's frankly about time the industry started moving in that direction. Pure hardware attributes only get you so far, and judging by the amount of integration time that went into this project, Microsoft would be doing itself a huge disservice to launch anything even close to not smooth-as-butter."

Because people relate to experiential products differently, each product fails differently. It might fail because we feel overwhelmed (Google Wave) or underwhelmed (Microsoft Zune). We might feel cheated (Classmates.com) or annoyed (Plaxo). We might feel frustrated (OpenID) or maddened (BMW iDrive). We might become enlightened to a need we didn't know we had, and then realize that another, different product would actually satisfy this need better (Pownce, Wesabe).

Why you should keep reading

What all the stories in my book have in common is that the products somehow failed to offer their audience a good experience. As a result the product either failed in the marketplace (e.g. Symbian) or the company was forced to change the product to offer a better experience in order to survive in the marketplace (e.g. Plaxo). The stories are sometimes sad, sometimes surprising, and sometimes enraging. But each one taught me something valuable about how to do my work, and I hope they will do the same for you.

I limited the case studies in this book to digital products, in particular software and consumer electronics. All the products examined here tried to innovate in one way or another before failing. There are certainly examples of failed products that attempted to copy others or simply to make incremental improvements over what came previously, but those cases aren't as interesting or instructive. I also excluded products that failed merely because the creators were incompetent or the lessons are outdated or irrelevant.

My key message in this book is this: experience design is an incredibly young field and we have much to learn about how people experience our products. However, there has been work over the past decades to address the challenges faced in this book, and the lessons others have learned can help us avoid failure.

Words: Victor Lombardi

This is an edited excerpt from Chapter 1 of Why We Fail, published by Rosenfeld Media.

Get 20% off the book with 'creativebloq'

The Creative Bloq team is made up of a group of art and design enthusiasts, and has changed and evolved since Creative Bloq began back in 2012. The current website team consists of eight full-time members of staff: Editor Georgia Coggan, Deputy Editor Rosie Hilder, Ecommerce Editor Beren Neale, Senior News Editor Daniel Piper, Editor, Digital Art and 3D Ian Dean, Tech Reviews Editor Erlingur Einarsson, Ecommerce Writer Beth Nicholls and Staff Writer Natalie Fear, as well as a roster of freelancers from around the world. The ImagineFX magazine team also pitch in, ensuring that content from leading digital art publication ImagineFX is represented on Creative Bloq.