Inside Games Workshop

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Founded in London in 1975, Games Workshop has grown into a very big business. The firm best known for tabletop strategy games like Warhammer: Age of Sigmar and Warhammer 40,000 recorded a £1 billion market value during June 2018, and expects its profits to double this year.

That’s due, in part, to the hard work and commitment of its dozens of talented artists. But that doesn’t mean it’s a stressful studio with constant deadlines to meet. “The environment is really informal, really relaxed,” says Dave Ferri, a concept artist who’s been with the company, now based in Nottingham, for about two and a half years. “It’s a very friendly atmosphere here.”

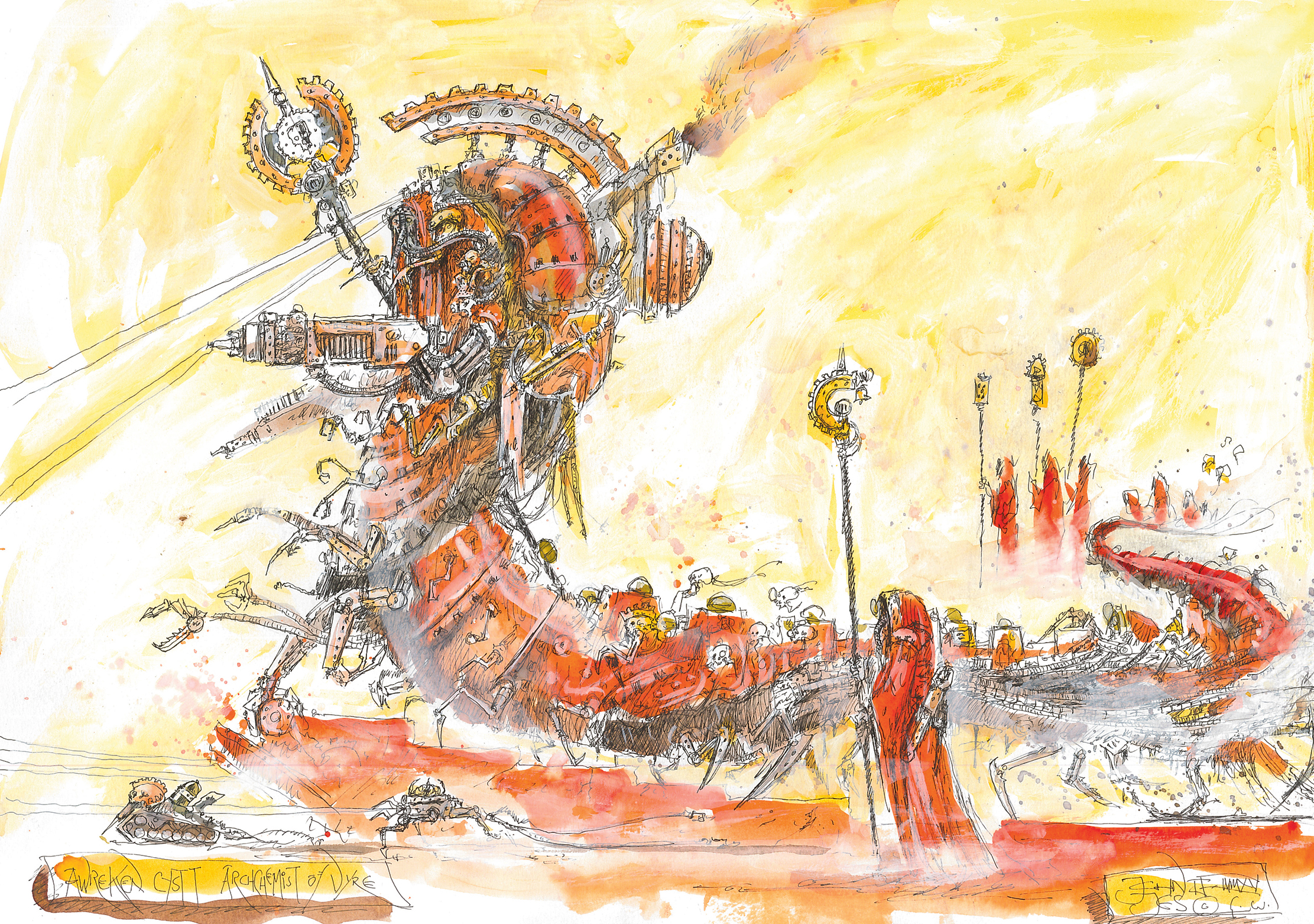

Ferri works with two other concept artists, John Blanche and Tom Harrison, to create the 2D illustrations that inspire the digital 3D art sculptors – 29 of them in total – who lovingly craft and produce the figurines. And there’s always work to do, says design manager Sam Dinwiddy, because the company is constantly developing new lines and doesn’t want to rest on its laurels.

“We’re always looking to excite our customers with something new,” Dinwiddy says. “We don’t just want to run through the list of ranges and update them all. That wouldn’t excite anybody. So we need to create stuff that’s unexpected, but still steeped in Games Workshop’s heritage.”

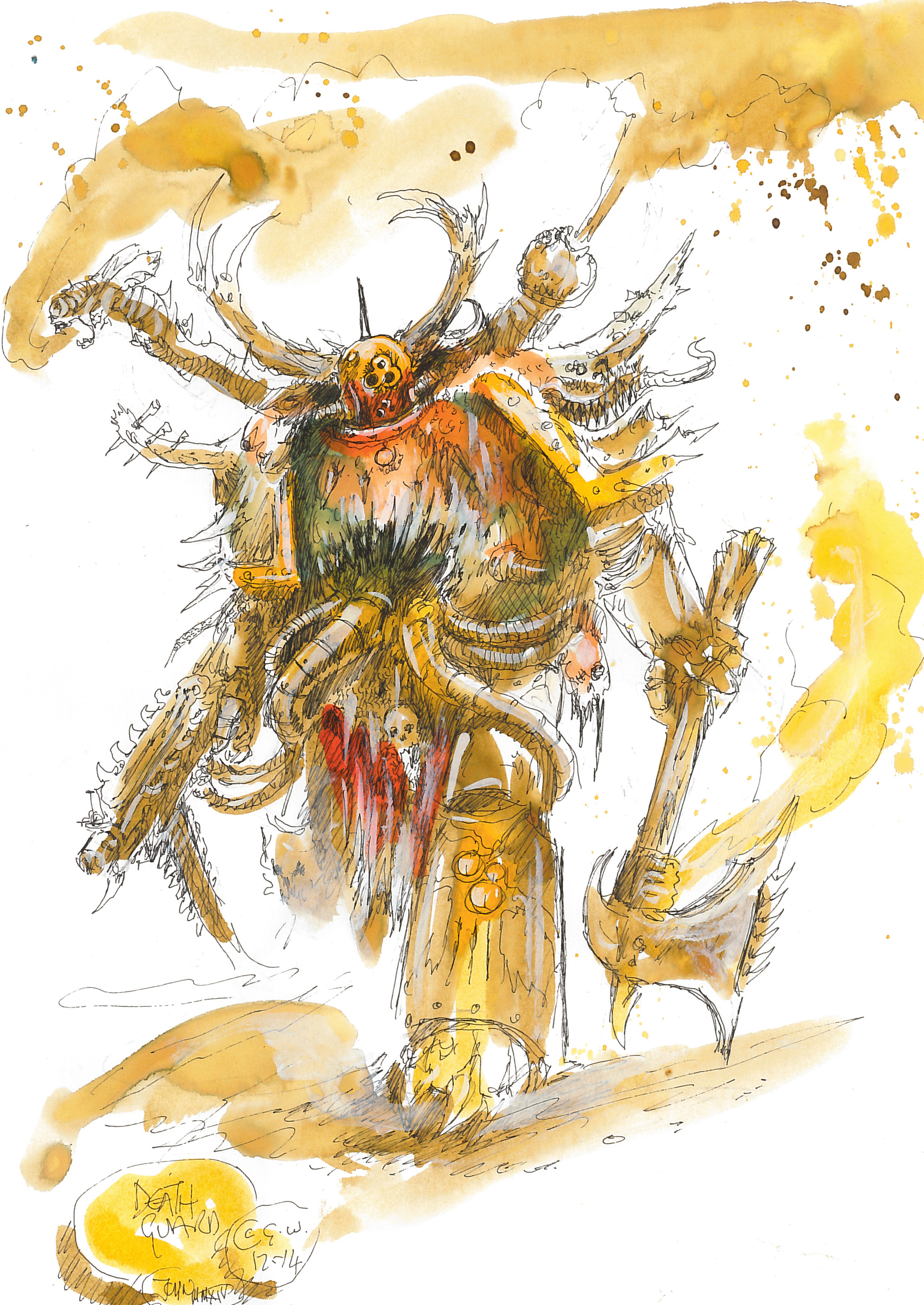

That creation process often starts with a simple sketch, says John Blanche, who first began freelancing for Games Workshop in 1977 and went on to spend three decades as its art director.

“Sometimes the designers like the sketch so much, they’ll actually make an image of it, but that’s unusual. I’m opening the doors up for sculptors to go: ‘Oh yeah, we could do that.’ It gives them a route to go forward.”

While Blanche works with physical inks and paints, Ferri creates most of his work in Photoshop CC on a Cintiq. “But the medium itself isn’t important,” says Ferri. “At the end of the day, the idea is what matters.”

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Typically, that design gets passed back and forth between concept artists and product designers in a process of re-invention and refinement. “It’s very organic and collaborative,” says Blanche. “We’re led by enthusiasm and deep understanding of each others’ backgrounds; it’s like one big family.”

Open and willing attitude

There are no ‘silos’ at Games Workshop, adds senior designer Seb Perbet. “One of the things that surprised me most was how open and willing people were to share their knowledge. I think it comes from the fact that we love this job and like talking about it.”

For the digital sculptors, Perbet explains, developing the miniatures is not just a technical challenge but a creative one, too. “I think the best product designers don’t separate these two aspects: the creative mind is the one suited to solving the hardest technical problems. So for me it’s hard to distinguish between the two, because as I’m sculpting I’m deciding what it is I want and how it’ll be manufactured at the same time.”

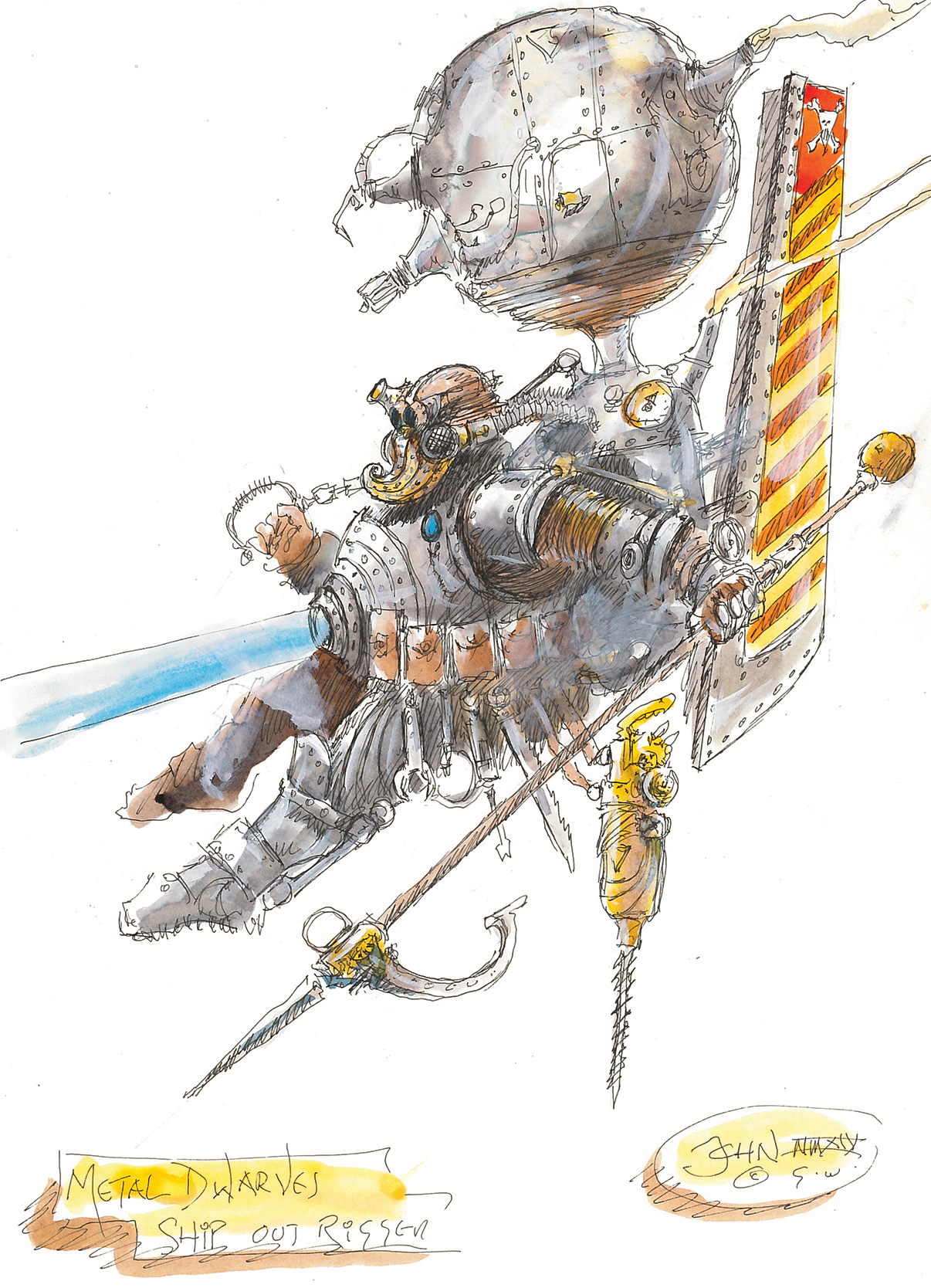

Even the 2D concept art needs to be approached with the physical end goal in mind. As Ferri points out, “These products are physically very small, and you can’t get a lot of detail in there. So our concept art needs to be bold and graphic, and most importantly, based on strong shapes."

Balancing the details

“That’s the hardest part: taking away the tendency to draw too much and strip it down,” Ferri continues. “You need to make the shapes interesting, because that’s where the product will succeed. So it’s important when you’re drawing something to stand back a few feet and have a look. Can you still see the details? Does it still read as you wanted it to? If not, you’ve probably made it over-complicated.”

And if you’re a fan of Games Workshop yourself, then here’s some good news: the company’s hiring. “Finding good artists is difficult, because it’s so niche,” says Dinwiddy. “So we’ll always look at portfolios and we’ll always listen to people; the only thing that we can’t guarantee is a job at the end of it.”

There’s no particular qualification or software skill that you need to have, Dinwiddy adds. “It’s literally just: do you have an affinity with sci-fi and fantasy? Can you generate fantastic, original and unique ideas quickly and consistently, in high quality? And do you have the passion to develop new IP for a niche business?”

If the answer to all those questions is yes, then you may get the chance to work in an environment where artists are constantly brimming with enthusiasm. “There’s always a good buzz in the studio, and we’re all really excited when new models come out,” says Dinwiddy. “I still get that ‘I want these!’ feeling, like I’m a little kid all over again.”

This article was originally published in ImagineFX, the world's best-selling magazine for digital artists. Buy issue 166 or subscribe.

Related articles:

Tom May is an award-winning journalist specialising in art, design, photography and technology. His latest book, The 50 Greatest Designers (Arcturus Publishing), was published this June. He's also author of Great TED Talks: Creativity (Pavilion Books). Tom was previously editor of Professional Photography magazine, associate editor at Creative Bloq, and deputy editor at net magazine.