Why are there so few D&AD Pencils in Design?

Why is Advertising still getting all the limelight? We investigate.

Whether you work in design or advertising, chances are you’ll know of D&AD. Founded as British Design & Art Direction in 1962 by luminaries Alan Fletcher, David Bailey, Terence Donovan and Colin Forbes, the not-for-profit has been nurturing, inspiring and rewarding creative excellence for almost 60 years — and it’s now truly global in its scope.

It all culminates in the annual D&AD Awards – set for 23 May this year. For many bigger agencies, it’s their main, sometimes only, contact with the organisation. Taking home a Yellow Pencil would be the highlight of most designers’ careers, but the elusive Black Pencil is the ultimate achievement.

Over the past two decades, the list of D&AD Black Pencil winners includes landmark campaigns such as Guinness’ Surfer, Cadbury’s Gorilla, Honda’s Grr, and more recent award-magnets Dumb Ways To Die, We're The Superhumans and Fearless Girl. Throughout the years, Apple has also strung together an enviable haul of Black Pencils for its genre-defining product designs.

But during that same period, the number of Black Pencils in graphic design and branding are thin on the ground, especially those created by smaller design consultancies rather than vast ad agencies.

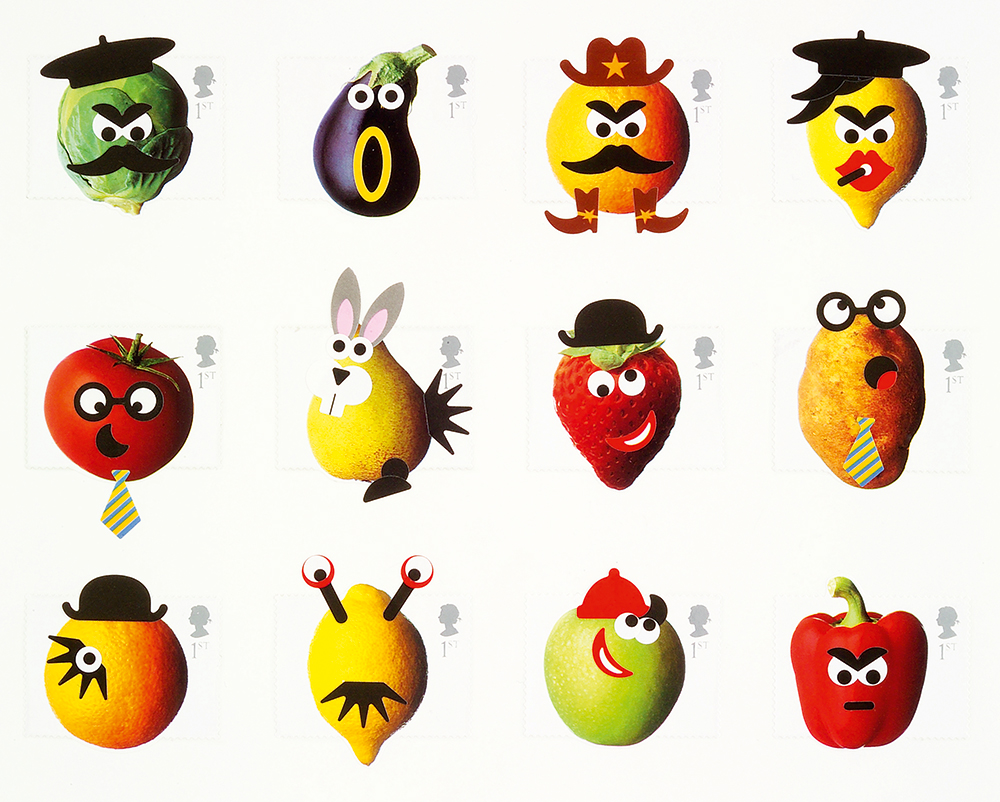

There have been notable exceptions. Back in 2015, boutique studio Made Thought took home D&AD’s highest honour for its stylish G. F Smith rebrand. Six years earlier, a young designer called Matthew Dent scooped the top prize for his coin designs for the Royal Mint. And another five years before that, Royal Mail’s quirkily interactive Fruit and Vegetable stamps landed Johnson Banks its first and only Black Pencil.

Yellow Pencils – and their recently-introduced lower-tier counterparts, Graphite and Wood – are a little more abundant in the design community. But compared to advertising, where a truly high-watermark ad campaign can yield a whole sackful of them across a dizzying array of categories, they are still rare.

So from Design’s perspective, are the D&AD Awards the final word in recognising the very best work – or does the scheme run the risk of being too elitist and too unaffordable for smaller studios to engage with?

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

Is the best work always rewarded?

"Winning a Pencil is the ultimate creative accolade," declares 2017 D&AD President Bruce Duckworth, co-founder of Turner Duckworth. By landing Yellow Pencils for design work for both Coca-Cola and Burger King, the agency disproved the assumption that big design clients couldn’t win at D&AD.

"The legacy of previous game-changing award-winning work, and the purity of the Awards, is unmatched," believes Duckworth.

"Win big and it can put you on the map," agrees Johnson Banks founder Michael Johnson, who was appointed one of D&AD’s youngest-ever Presidents back in 2003.

Over his career, Johnson has won a clutch of Yellow Pencils as well as that coveted Black, and most recently the annual President’s Award. "The problem is, very few people in Design win big," he says. "Recently we got three projects in the D&AD Annual, and won a prize for being one of the most awarded. It was almost surreal."

One senior creative figure, who preferred to remain anonymous, confesses a love-hate relationship with D&AD: "I love it for what it does, what it represents and the Awards show. I hate it for the same reasons. I wish it could do more of the good bits, and I wish the Awards were not so frustratingly bureaucratic. And winning a Pencil is so damned hard."

Does the best work always rise to the top?

According to Johnson, the system is a little flawed in that respect. "People see D&AD as the ultimate arbiter of quality, but what people fail to realise, until they judge themselves, is that there are dozens of juries," he says, slightly lifting the D&AD curtain.

Another leading creative, who preferred to share their views anonymously, argues that the younger generation of designers increasingly see less value in awards. "We hear many reasons why – cost, outdated concept, elitist and so on. But I can’t help feeling that creative insecurity is driving a ‘mutual support’ social media, where ‘I’ll like your work if you like mine’ replaces genuine innovation and improving standards."

"In the short term that’s ok, but longer-term – and for the industry – it’s a disaster. Work is becoming homogenised, standards are dropping and nobody seems interested in doing truly innovative and brave work."

Is It harder to win in design than advertising?

"For many, D&AD has religious meaning," enthuses Greg Quinton, chief creative officer at global mega-agency Superunion. "I have always been, and always will be, a believer."

Formed from five smaller agencies in the WPP network, including multi-award-winning consultancy The Partners, Superunion can boast a collective total of 34 Pencils from the past decade alone. That includes 30 Wood, three Graphite and one rare Black, won by The Partners in 2008 for its National Gallery Grand Tour campaign. Tellingly, however, this was awarded in an Advertising category: the project was only awarded Wood Pencils in its corresponding design categories.

"They will aim for, say, nine judges per category, but inevitably someone gets sick or stuck at customs. Before you know it you have six. You can’t judge your own work – you have to abstain. So you may be in a situation where if three people dislike or don’t understand the project (for whatever reason) then bang, out it goes. That’s why results can seem random, because they sort of are."

While Duckworth admits the jury system isn’t perfect, he defends the set-up: "D&AD attracts the best people from all over the world to judge, each jury has a unique dynamic and will therefore make slightly different choices to another," he says. "The work awarded is the best for the particular jury that selects it. Although not everyone will like the choices they make, I can’t think of a better way."

Nonetheless, many designers welcome the rarity of the top Pencils in Design. "It’s rightly hard to get work in the book, regardless of Pencil colour," asserts Jim Sutherland, founder of two-person studio Sutherl&. "Branding has always been particularly hard to get into – but it’s one of the hardest disciplines in which to do great, all-encompassing work."

"Graphic designers are incredibly critical of their own work, and rightly so," Sutherland continues. "So it’s unsurprising that we are just as critical of others." Nevertheless, he acknowledges that some landmark design projects that have seemed sure-fire big winners have been shot down – both Sutherland and Johnson cite Why Not Associates’ stunning Comedy Carpet as a notable ‘one that got away’ at D&AD.

GBH co-founder and 2015 D&AD President Mark Bonner has picked up four Yellow Pencils since 2005, all for PUMA – as well as 35 Wood and Graphite Pencils. However, he concurs that the inherently critical nature of the average designer has an impact on how Design fares in comparison to Advertising.

"Design does love a whinge," he says. "Advertising doesn’t start from that position. Their whole mindset is how their industry can gain from involvement with an organisation like D&AD. They have a real world view, and there are a vast array of awards that are pursued by the networks. They invest a lot of money in it."

As Duckworth points out, some advertising campaigns could potentially be judged from many different angles – from the media format they’re seen in, to the crafts employed in creating them – and large agencies with healthy budgets will often submit a figurehead campaign across a wide selection of categories. "That means if one campaign wins, it can win big," he adds. "Designers tend to be more selective with their entries."

"Put a group of designers in a hall at D&AD and they go into this semitrance-like state obsessing about ‘finding the best piece in the room’," adds Johnson.

"With hundreds of entries, the chances of those seven designers all agreeing on the same 20 projects are very, very slim."

"Designers come hard-wired to knock stuff out, not put stuff in," he continues. "They fillet 20 shortlisted things down to 12, then to three, then to one. However hard you try, however diligently you brief, encourage and cajole, this is what happens. Meanwhile, the ad industry shortlists 35 in a category, nominates 14 and gives nine of them Pencils. It’s frustrating."

"In Advertising, the mindset is that the whole industry can benefit," continues Bonner. "They don’t look to shrink the winners, they seek to grow the winners – a win for one agency is a win for them all. In Design, our mindset is: ‘But is it perfect?’ People bring their full quotient of purism, and make sure nothing imperfect sneaks through."

"When I was president I really tried to challenge this. I think design does have to look at this more as an opportunity to celebrate our industry and say: ‘That’s great work, let’s big it up and not look for what’s wrong with it.’ The more great work that clients see, the better it is for our industry. I think Advertising has had this figured out since the late 1960s."

Are there more important things than pencils?

On a broader scale, the D&AD Awards are really just the tip of the iceberg in terms of how D&AD supports the industry. As CEO Tim Lindsay puts it: "Our purpose is to stimulate, celebrate and enable excellence in commercial creativity, in the belief that great work delivers better outcomes – commercially, culturally, socially, politically and environmentally."

Lindsay outlines four key strengths for D&AD: "Our reputation, our integrity, our standards, and the fact that we’re a charity, and put all the money we make back into the industry." That pledge to put back into the industry, nurturing the next wave of Pencil-winners in the process, is a huge part of D&AD’s mission – and initiatives such as the New Blood Festival and Awards are instrumental for developing the next wave of talent.

"I remember being in a meeting with [2013 D&AD President] Neville Brody where we drew a circle and said: ‘That is our strategy,’" recalls Bonner.

The mantra is simple: win a Pencil, and it’s your responsibility to teach one – thus completing the virtuous circle. Bonner draws attention to D&AD’s New Blood Shift initiative in particular for opening up opportunities to talented creatives who haven’t taken the university route.

"Even if they found one talented person every two years that would be worth it, but they’re finding 15–20 every year," he argues. "I couldn’t afford uni back in the day – I was grant-funded all the way through the Royal College of Art – and kids like me can’t access that quality of education now."

Sutherland agrees that D&AD’s role for celebrating creative excellence is counterbalanced by a responsibility to improve design education at all levels. Upon his graduation in 1988, Sutherland had never heard of D&AD until his tutor introduced him to that year’s Annual. "The Partners had a lot of work in that year in particular, so I applied there," he recalls.

Since then, Sutherland has amassed a staggering 85 Pencils. Many were through hat-trick design, the agency he founded with Gareth Howat, but eight of them came in 2017 alone – when in an inspiring coup for small studios everywhere, his two-person operation Studio Sutherl& was D&AD’s Most Awarded Design Agency.

"In the current climate with all arts education being ignored, cut and unappreciated, I think D&AD’s role is absolutely vital," he continues. "Learning and training does not stop when you leave college – it carries on throughout your working life."

Bonner also believes that D&AD could, and should, work harder to engage client-side creative luminaries. "A kind of ‘Hot 100’ of creativity commissioners could be really valuable," he suggests. "There is the Most Awarded Client at the D&AD Awards, but I think D&AD could do more in general to showcase brands that have really got return on investment on creativity."

"There are very few Black Pencils in Design. D&AD wants them to be hard to win, and for juries to argue late into the night," adds Bonner. "But business doesn’t really get that. We’re looking for what’s wrong with a project, and always wanting a ‘perfect 10’. Clients want to see work that they can buy."

Is D&AD too focused on advertising in general?

D&AD was founded with the intention of representing Design and Art Direction equally – two complementary disciplines, joined by an ampersand. Its Presidents traditionally alternate between different sides of the coin each year, and Johnson, Bonner and Duckworth were well-placed to give the Design agenda a voice during their respective stints at the helm.

More recently, 2018 President Steve Vranakis and current President Harriet Devoy have broken the dichotomy a little by representing the client-side, as creative directors at influential global brands Google and Apple respectively. Despite his personal successes in the D&AD Awards, however, Sutherland believes the balance is still a little off:

"There’s generally not enough emphasis on the hundreds of small design studios," he says. "It’s just too expensive for them to enter and go to the Awards or the Festival. It’s definitely weighted in favour of bigger design and advertising companies."

Another creative director, who chose to remain anonymous, goes further, calling D&AD’s design-advertising balance "way out of whack", and arguing that the divide looks insurmountable unless the design community is listened to and awarded in an equitable way.

As a former D&AD President from a relatively small, independent agency, Bonner offers a pragmatic view: "You sometimes hear the loudest voices from the smallest agencies in design, and that’s a great thing," he observes. "You know: ‘It’s expensive; it’s too bloody hard to get a win.’ They can feel a bit ignored. But there is a commercial reality there too."

As Bonner points out, D&AD is a registered charity – unlike most industry awards schemes – with profits feeding back into supporting the industry, and making great work more likely. "They need the industry to back it," he continues.

"In my experience, Design is passionate about it, but simply isn’t able to back it financially as much as Advertising is." When Bonner was President in 2015, he recalls, roughly two thirds of D&AD’s income from entry fees to the Awards came from around 15 large ad agency networks. "That’s a cold hard fact that Design could do well to think about," he adds.

One prominent creative director we spoke to suggested that the Cannes Lions have "ruffled" D&AD in recent years, and suggests that the D&AD Awards should pull away from its big adland rival rather than try to compete. "It’s the ad industry money that keeps it alive, yet it’s the ad industry bias which stops it being truly representative."

"People in D&AD love working with people in Design, because we are so passionate about it," continues Bonner. "But Design can be quite tribal. We may have historically felt marginalised by our big brother: Advertising. But Advertising doesn’t think like that. It thinks Design is where it’s at, and is moving towards our skill set. It’s about big overarching 360-degree thinking."

D&AD is aware of the perceived divide, but Lindsay insists the organisation works hard to achieve the right balance, whether it’s at board level, amongst its New Blood briefs, at the Festival, within the Awards categories or through the extensive industry training it offers. "I’m sure we are in error sometimes, but we’re always ready to listen to advice," he adds.

Duckworth agrees, and lays down the gauntlet to D&AD’s more outspoken critics: "If designers want to be more represented, they should be more proactive," he urges. "D&AD is a charity, and supporting it supports the industry as a whole. This feels like a great time for Design, so get involved."

This article was originally published in issue 289 of Computer Arts, the world's best-selling design magazine. Buy issue 289 or subscribe to Computer Arts.

Related articles:

Nick has worked with world-class agencies including Wolff Olins, Taxi Studio and Vault49 on brand storytelling, tone of voice and verbal strategy for global brands such as Virgin, TikTok, and Bite Back 2030. Nick launched the Brand Impact Awards in 2013 while editor of Computer Arts, and remains chair of judges. He's written for Creative Bloq on design and branding matters since the site's launch.