Aaron Blaise reveals why he quit his dream job at Disney

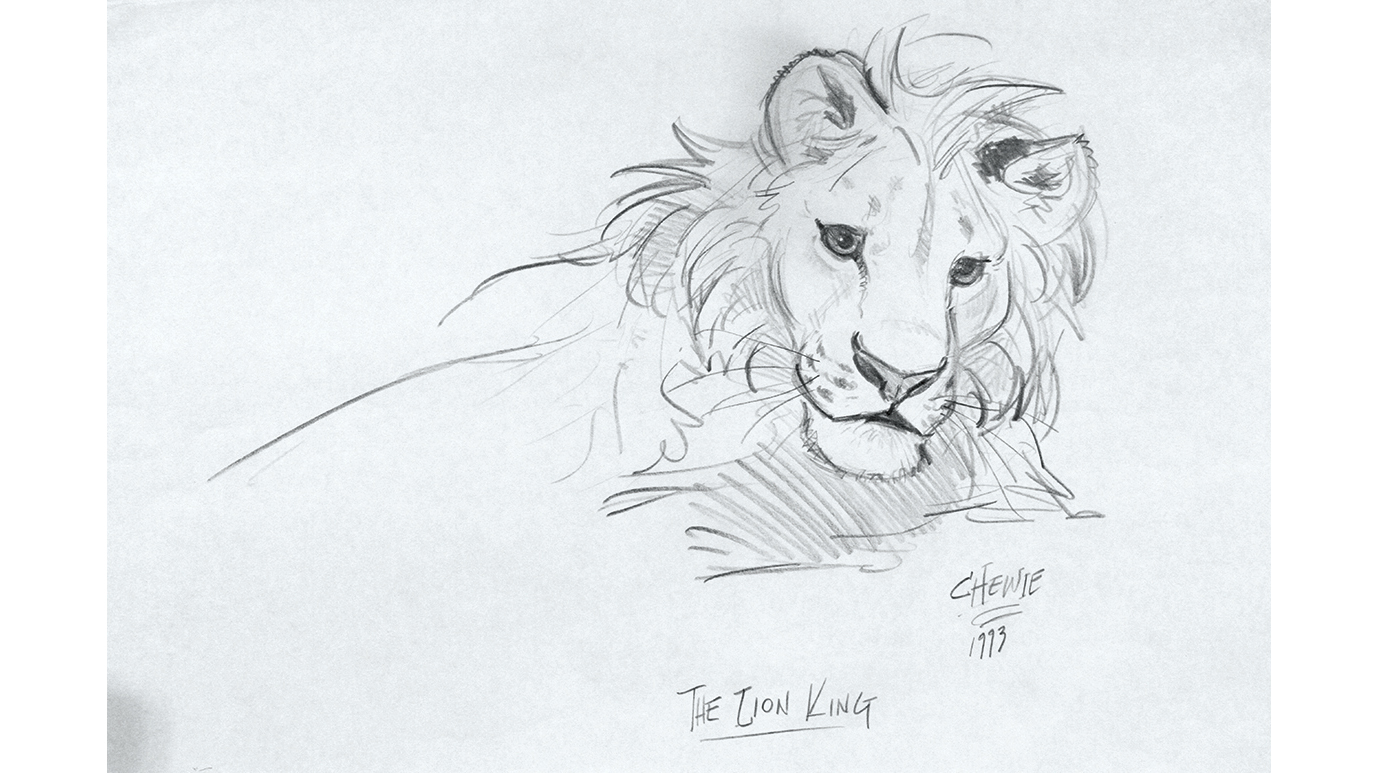

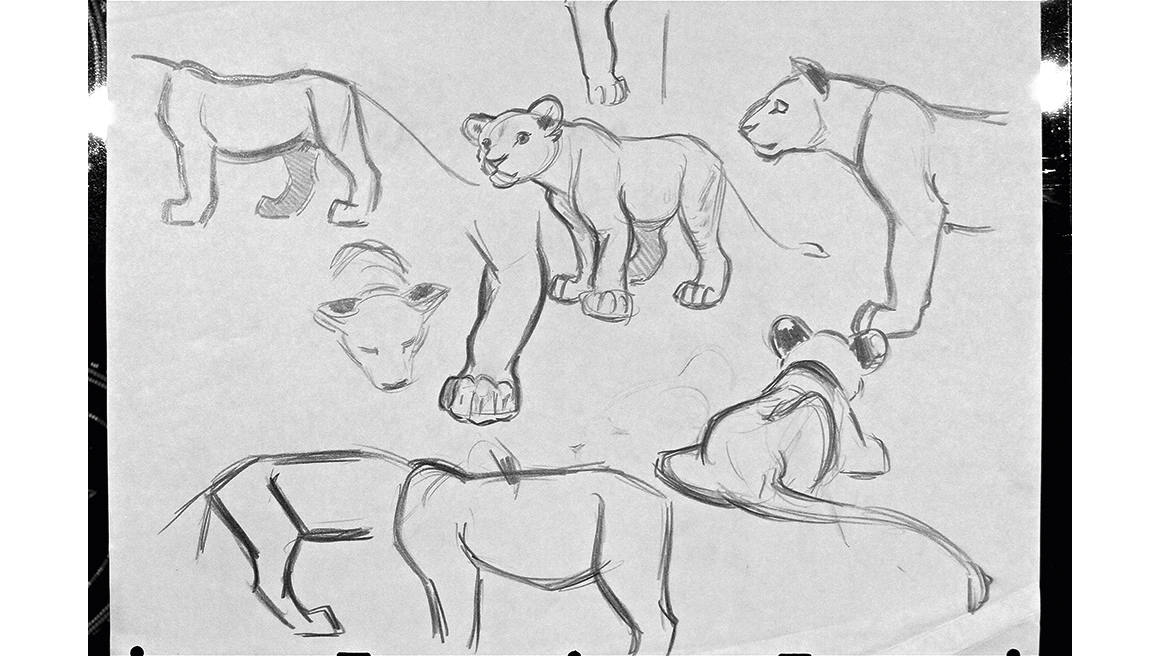

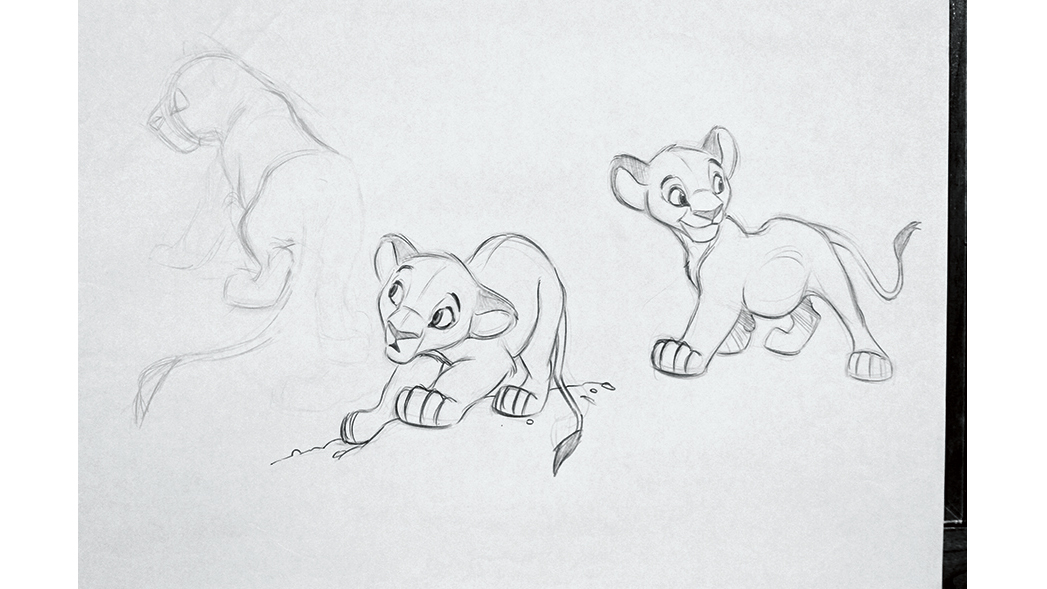

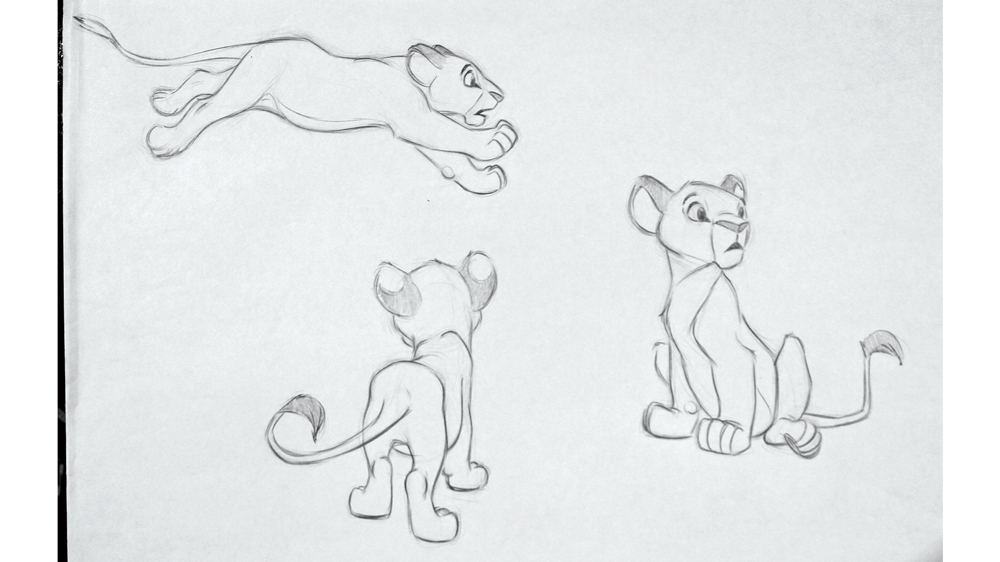

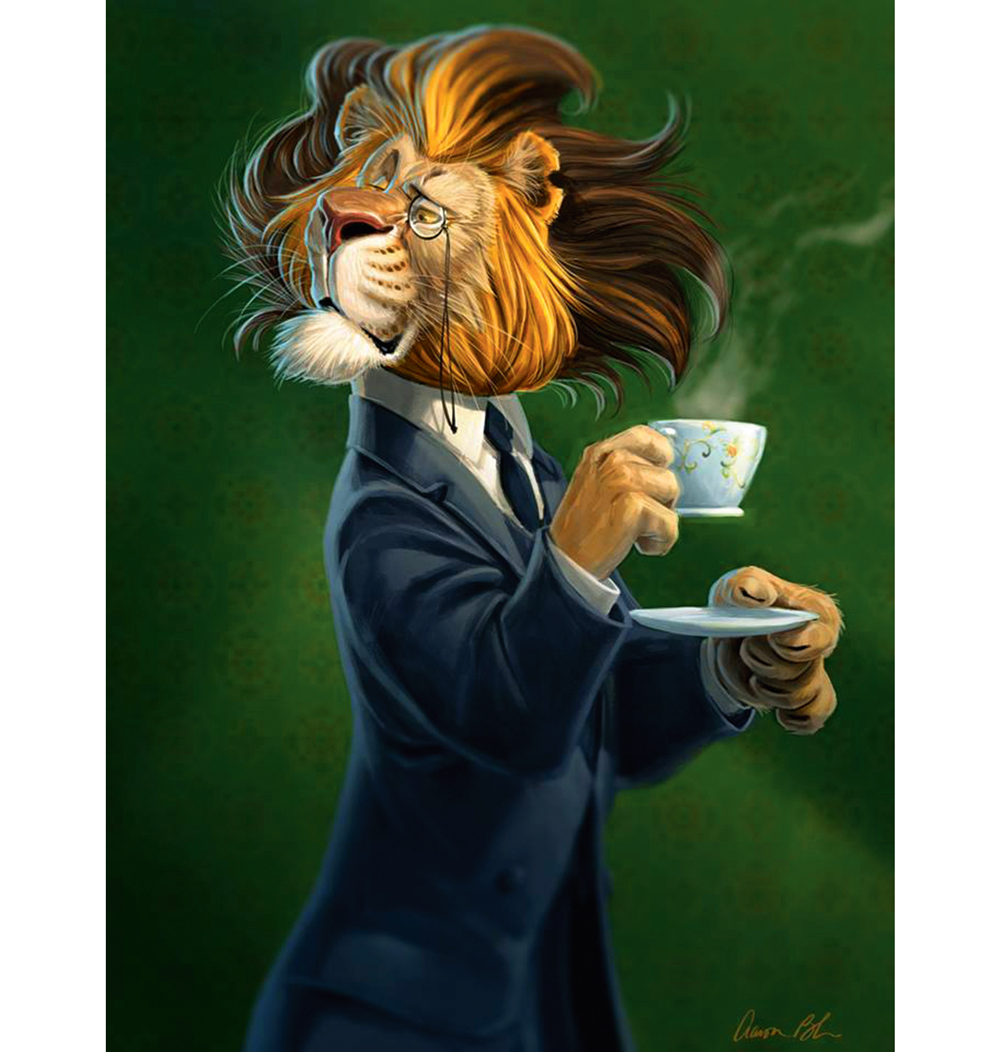

Plus: See Blaise's beautiful early Lion King character sketches.

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Aaron Blaise has a good story for you if you've ever wondered what it was like working at Disney during the 1990s. He’d just finished Aladdin (1992) – the movie before was Beauty and the Beast (1991). Disney was on one of the great streaks in cinema history. It began with The Little Mermaid (1989), ended with Tarzan (1999), and included many of the biggest animated films of all time.

Blaise was promoted to supervising animator on The Lion King (1994). He was in charge of his own character, Simba’s best friend, the young Nala. The anatomy had to be perfect. This lion cub needed to move the way that lion cubs really move. So Blaise went to a kind of workshop, a kind of figure-drawing class, the kind of thing that could only happen at Disney during the 1990s.

Make sure you grab your ticket for Vertex 2021 to hear more from Blaise as he talks us through the old ways of animation. Our event for 2D and 3D artists takes place on 25 February but don't worry if you can't make it, a ticket grants you on-demand access to the talks for 30 days. What are you waiting for? Get your ticket for just £25 today.

(If you're in need of some inspiration for creating great characters, check out our how to draw tutorials and article on character design.)

Different times

These were different times. No internet, no video conferencing, no emailing images back and forth. Blaise worked at the Disney studio in Florida, but the California studio was also working on the movie. That’s a whole country, a whole timezone apart. Blaise photocopied his designs, numbered them and sent them by courier to Los Angeles. It was the same with tapes of animation. Meetings with directors took place on the phone the following day when the stuff arrived. By then, Blaise was on to something else. If things needed amending, he had to switch back to the previous design or animated clip.

So a full week’s work might have equalled only a few seconds of finished movie; one or two shots. A film like The Lion King was 90 minutes long and contained 4,000 shots.

Before he could begin, Blaise needed to know the script inside-out. He needed to make sure that his designs matched up with the art director’s vision. And he needed Nala to be believable: a character, not a caricature. That, he says, was what Disney did well: it made believable characters by “pulling from reality.”

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

So how did Aaron go about creating a believable lion? At Disney, during the 1990s, it was done like this: “We would draw them from life,” Blaise says. “They would bring the lions right into the studio for us. They’d walk them back and forth across the stage, and we would analyse their movements and anatomy, and everything else, and get it down on paper.”

Wild Child

Blaise grew up in Florida. His family lived in little trailer north of the Everglades, near a place called Corkscrew Swamp. He was “a wild child” who never wore shoes or a shirt and was often covered with ticks. Florida was his own private paradise. He always drew and painted, but he couldn’t see anyway of making a living from it. Then, aged 17, Blaise’s home burned down. Things got “a little rough.” He was ready to give up art and get a job in forestry. But Blaise’s stepdad persuaded him not to waste his ability.

Blaise graduated with a certificate in illustration from the Ringling College of Art in 1989. His first professional job, aged 20, was an internship at Disney. There was just one problem: he couldn’t animate. He knew drawing, he was good at that. But he couldn’t get his head around movement. He had this dream job, but he almost quit. Then mentor Glen Keane told him: ‘Keep trying. It’s going to happen. It’s going to happen.’ And then three weeks later, it happened, it clicked, and seemingly out of nowhere Blaise understood arcs and timing, and slowins and all this other technical stuff. “I could see it happening in my head just because I was living it, breathing it, dreaming about it.”

He went full-time at 21 and worked his way up to director, earning an Oscar nomination for Brother Bear (2003). Then Disney’s great streak came to an end. It closed the studio in Florida which employed 365 people. Everybody was laid off except Blaise and nine others, who were then moved to California.

“Things change,” Blaise says. “The market changed, the finances for things changed. It was very hard to see my friends and people that I had grown up with, spent the past 20 years with, to see them all of a suddenly without a job and scattered to the four winds. And so that was my first big blow."

Blaise, his wife Karen and their kids all moved to California. They started over and pretty soon Blaise was making movies again. Then Karen was diagnosed with breast cancer. Disney helped Blaise set up shop at home. Some co-workers joined him and he was able to work and look after Karen.

“But, ultimately,” Blaise says, “two and a half years into it, on 11 March 2007, she passed away in my arms, and that was a devastating blow for me. I mention this a lot in my talks: how you need to be driven to do your work. And, after I lost Karen, I lost my drive. She was my soulmate. She was the love of my life and I was completely lost and heartbroken and my kids were a mess as well. And so trying to go back to work with that mental baggage and heartache and pain, and trying to make a movie and direct those people, for me, it was almost impossible. It was impossible.”

Losing my identity

Blaise stuck it out for a couple of years. But his desire was gone. Studio bosses removed him from the movie he was working on and said he was done as a director. They wanted him to stay with Disney in another role. Blaise quit. “It was the most difficult and scary decision I’ve ever made in my life because I didn’t know anything other than Disney. My whole identity was my family and Disney, and Disney was falling apart, and my family was falling apart. So I was losing my identity.”

What did he do next? First, he went home and he panicked. Blaise had a big mortgage but no longer had the director’s big salary to pay for it. Next day, he went into work and cleaned out his desk. There was a job offer waiting for him – in Florida. “It was unbelievable, the timing of it all.” The company was Digital Domain, a visual effects and digital production company. Director James Cameron was one of the founders. Still, this wasn’t Disney. There would be no lions brought in for figure-drawing classes.

Blaise was three years into a movie when the company went bankrupt. He was jobless again. The artist considered going back to Disney. Then he got thinking about the way Glen Keane used to push young artists. He wanted to do something similar. Blaise and business partner Nick Burch came up with CreatureArtTeacher, offering lessons and tutorials based on Blaise’s long and illustrious career. “I decided that I really didn’t want to place my career – my future – in the hands of any executives anymore. I wanted to be the director of my own life.”

Blaise works digitally and in most traditional mediums. From Alaska to Africa, he’s photographing wildlife for reference. It’s important to see subjects in person. Working traditionally, he starts with thumbnail sketches to figure out composition. He draws the image on to the canvas, tones the canvas, then works through the rendering. But digital’s different.

Sometimes he sits down to draw without knowing where it’s going to go. This brings another dimension to his work. Working digitally helps him find compositions he would never have found working traditionally.

Memento from Disney

His studio is at home: a small room that’s divided into into two spaces. One side is for digital work, comprising a desk, Mac Pro, Cintiq 32-inch and a couple of monitors. He uses Photoshop and TVPaint Animation. These day, all animations are done digitally. But he keeps his old desk from Disney – the very desk he used working on all those great movies. He uses it for painting with watercolours now. Blaise’s traditional setup continues with an easel for working with oil, acrylics and charcoal. There’s a large bookcase that’s full of books, and lights and cameras used for shooting video lessons. Twice a week, he does a livestream show with his son Nick.

Routine is important. These days, he’s at his desk at 10am. He could be painting, drawing digitally, making a video or working on lessons his teaching courses. But he sticks at it until he’s “mentally spent.” Could be a couple of hours, could be 10 hours. The thing is to be working consistently every weekday. Being his own boss takes a lot more discipline than the structured nine to five at Disney.

So does he ever regret leaving? Would he do anything differently? People often describe Blaise's art as Disney-esque. He doesn’t mind. He started at the studio when he was 20 and left when he was 42. Disney was a big part of his life. But his time there went hand in hand with the biggest part of his life.

Blaise often wonders what might have been had Karen been diagnosed earlier: “If Karen had lived, then what would my life be? I can’t compare it.” Professionally, maybe he’d still be at Disney. Perhaps he’d be directing his fourth movie now. Who knows? But what he does know is that working for himself is ultimately more rewarding than working for a studio.

So the short answer is no. He doesn’t regret leaving Disney. “It was probably the best decision I’ve ever made in my life. But, you know, it’s funny, I don’t know that there’s anything I could do differently. I look at where I am right now, and, creatively, I’m happier than I’ve ever been because I’m able to draw, paint, animate, whatever I want to do to my heart’s content. But it all came about because of the death of my soulmate.

“It’s a little sappy, but there’s truth in this. I was thinking about my wife Karen and what she would think about me going on to do whatever I was going to do. I really felt strongly – I still do – about doing something that she would be proud of, that she would want to do, that would drive her, because she was always this very giving, loving individual. And so that was also a big part of our decision-making process in creating CreatureArtTeacher.”

This article was originally published in ImagineFX, the world's best-selling magazine for digital artists. Subscribe to ImagineFX.

Read more:

Gary Evans is a freelance journalist and travel writer. He is a former staff writer for Creative Bloq, ImagineFX, 3D World, and other Future Plc titles.