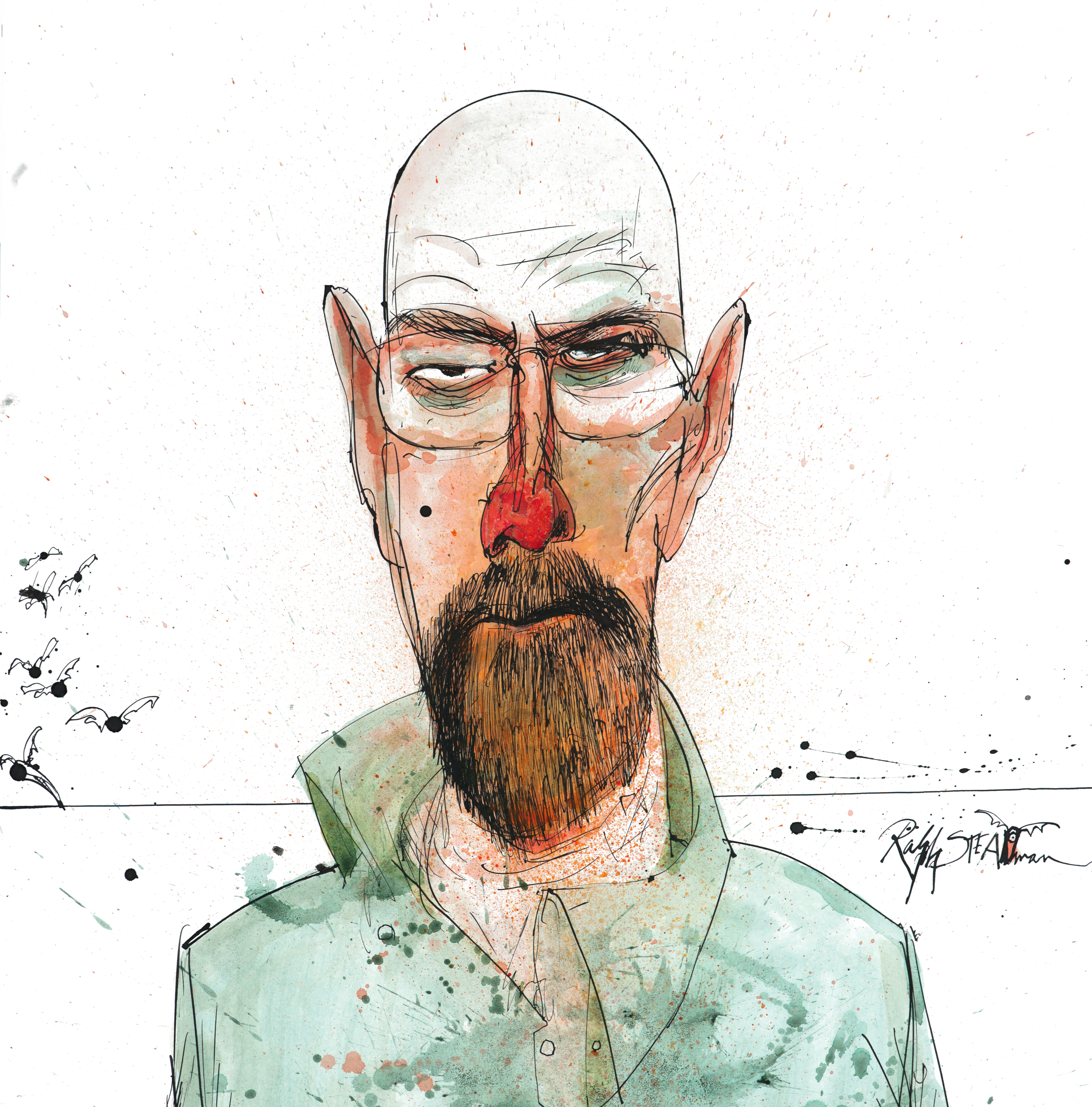

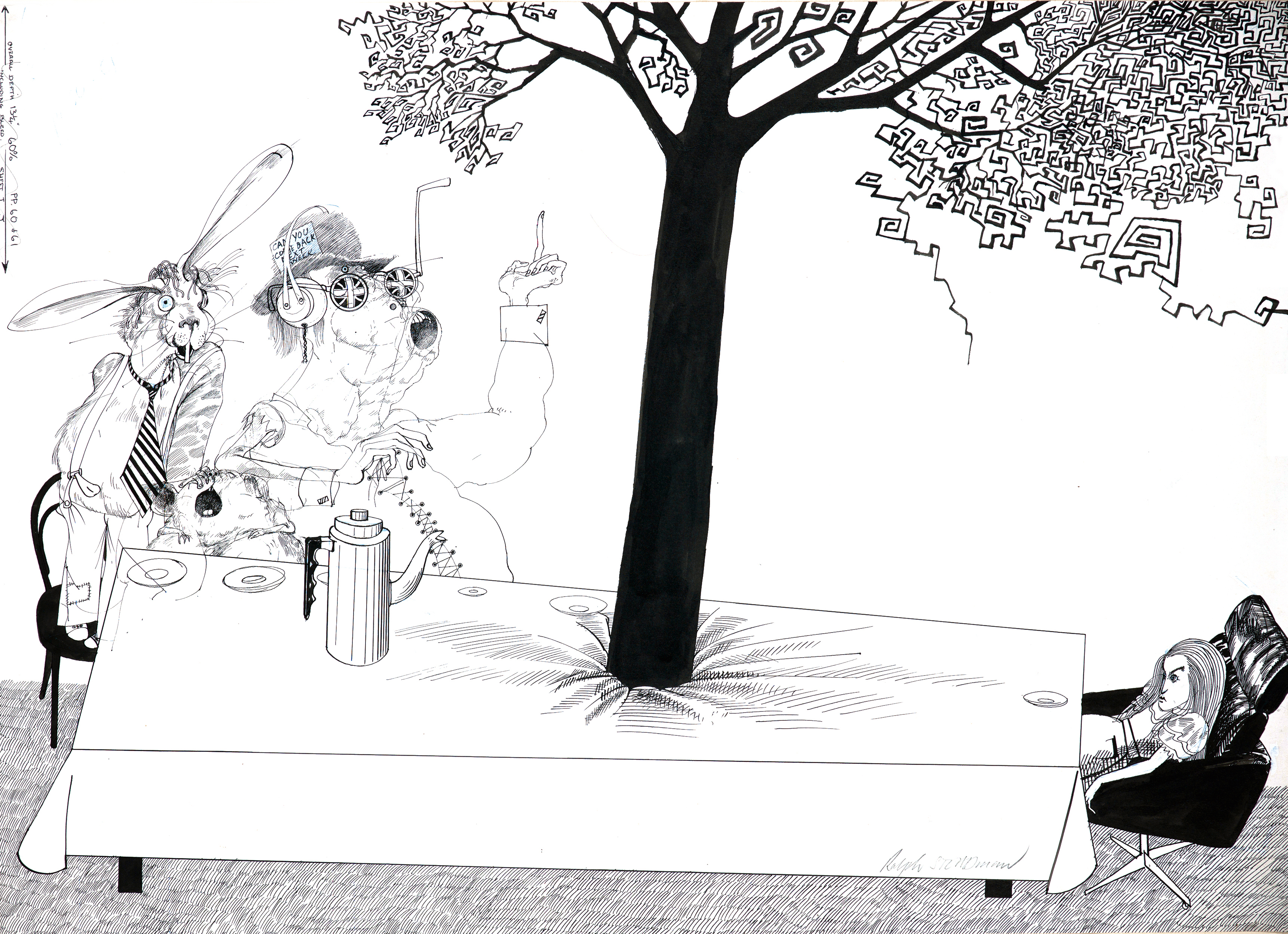

Inside the gonzo art of Ralph Steadman

We chat to the British artist about his anarchic artwork.

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

The first time I speak to Ralph Steadman, he interrupts me at hello. "You're Gary Evans, right?" he says. "Evans, Evans, Evans and Evans: they're a company of some sort. I call them up." He broadens his slight Welsh accent: "'Could I speak to Mr Evans?' 'He's in a meeting.' 'Perhaps I could speak to Mr Evans?' 'I'm afraid he's on holiday.' 'Oh. Maybe I could speak to Mr Evans?' 'Unfortunately, he's not been too well.' 'I see. Can I speak to Mr Evans then? 'Speak-ing!'" He laughs, thoroughly, and I never regain control of the conversation.

Ralph’s stories meander through topics including, but not limited to, aircraft engineering, a pig farm, the Kentucky Derby, yacht racing, boxing matches, marathon running, Scientology, extinct and endangered animals, Leonardo da Vinci, Sigmund Freud, guns, Donald Trump, and, of course, Hunter S Thompson. His conversation is like his work: chaotic, yet perfectly ordered.

What separates artist and art is violence. He shows no sign of it; his art is full of it. Ralph in real life is your favourite uncle. Ralph on the page is your worst nightmare.

The artist spent much of his early career as a cartoonist for British newspapers. While in America, in 1970, he received a call from the editor of a magazine – the short-lived Scanlan’s Monthly ("named after a Nottingham pig farm, for some peculiar reason …") – who asked if he’d like to cover the Kentucky Derby with a journalist named Hunter S Thompson.

The idea was this: Thompson returns to his hometown, Louisville, to cover the Derby, but instead of writing about the famous horse race, he writes about its infamous spectators, their drunkenness, their crudeness… and Ralph illustrates the whole thing.

The pair end up being every bit as drunk and crude as their subjects. The article reaches its climax when Thompson catches his reflection in a mirror. Staring back at him is ‘that one special face we’d been looking for … a puffy, drink-ravaged, disease-ridden caricature.’

The reporter had become the story. An editor at the Boston Globe described the article, titled The Kentucky Derby Is Decadent and Depraved, as ‘pure gonzo.’ Ralph, however inadvertently, had helped Thompson invent a completely new style of writing: gonzo journalism.

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Together they went to the 1970 America’s Cup yacht race (they attempted to graffiti one of the boats while under the influence of hallucinogens), 1974’s Rumble in the Jungle boxing match (Thompson sold the tickets, so they never saw Muhammad Ali and George Foreman fight), and the 1980 Honolulu Marathon (they stood on the home straight and shouted abuse at competitors). Ralph didn’t go with Thompson on the trip that would become Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, the writer’s most famous work, but he illustrated the book.

"I said, ‘No one would have noticed that book if it wasn’t for my drawings.’ He said, ‘How dare you, Ralph!’ It’s still, somehow, become part of what I’m known for. I did have an affect on it, because I did the drawings. They were the kind of drawings… we just hadn’t had anything like that. They were slightly crazy because I was trying to step up to the plate, as they say, and do something special to suit Hunter’s weird style of writing."

They were opposites in many ways: Ralph the quiet, gentle Brit, and Thompson the loud, violent American. But they shared a vision, a distrust of authority, a compulsion to speak truth to power. Their repeated takedowns of the disgraced ex-president Richard Nixon are among the most brutal in the history of satire. It’s impossible to read Thompson’s words without seeing Ralph’s pictures, and vice versa.

Going in with the ink

Ralph describes his art as, "Erratic, controlled, sometimes complex, and interesting – even to me." He carries a sketchbook in which he doodles and notes down ideas. He takes these ideas into his home studio and works up the best ones, the "most evocative."

He never uses a pencil. He goes straight in with ink, black Indian ink, usually a big splash of it, thrown onto the page with a practised flick of the wrist. He sees an image hiding within this blot, or else he drags one out of it.

He uses a pen with heavy bronze nib, and he scratches and he smears. He draws around the splash, adds to it, takes away. He uses an ink compass, and sometimes a diffuser to spray ink over the page. The result is occasionally light and playful, but more often than not it’s dark and unsettling.

"Accident is important," Ralph says. "I am never afraid of mistakes. A mistake is an opportunity to do something else. It evolves. I must see wet ink. I must see it on a page. I can’t construct everything inside a computer. The drawing is wet ink. I see a lot of drawings and know they’ve been done on a computer, and there’s no life in them."

Ralph was born in Wallasey, near Liverpool, in 1936. His mother was Welsh. When the war started, they moved to Wales, to the more remote Abergele. As a boy, he built model planes. After leaving Abergele Grammar School at 16, he worked as a trainee engineer at the nearby De Havilland Aircraft Company. He hated life in the factory and quit within a year. But it was here that he learned technical drawing: the geometric shapes that would feature throughout his career as an artist.

Next, Ralph took a job as stockroom boy in a department shop. Here he learned – or cemented – his distrust of authority. "I was sweeping the floor at the front of the shop," Ralph says, in an accent somewhere between Welsh and Liverpudlian, "and along came this headmaster, this hideous headmaster. He said, ‘Look at you. You’ve ruined your life. You could have been something if you’d stayed at De Havilland.’ I was only a bloody 16-year-old boy."

Ralph saw an advert in a newspaper for an art correspondence course. It read: ‘Learn To Draw and Earn Pounds.’ He signed up and practised his drawing during military service, working as a radar operator in the Royal Air Force. He drew in barracks and in pubs. He charged a pint for his pictures.

He later moved to London, took evening classes at East Ham Technical College, and studied at the London College of Printing and Graphic Arts. He freelanced as a cartoonist for satirical magazines like Punch and Private Eye, and began illustrating books.

During this time, Ralph became friends with Gerald Scarfe – the cartoonist who went on to create artwork for Pink Floyd. They practised together and agreed to send work to the same publications. Ralph annoyed Gerald going it alone at Private Eye. Their friendship never recovered, but their art remained similar.

"Eventually," Ralph says, "he more or less took over my style of work. My first wife, unfortunately, wrote him a letter and accused him of stealing my approach to things. That finished it. We were never friends again."

Ralph starts the day with a swim. And then, from 9am until lunchtime, and from 2pm until early evening, Ralph works in his home studio. Books fill shelves. Ink pens and paint brushes cover every surface. Pictures hang on the walls, other people’s art, his own too, because he never sells originals.

There are wooden stools for perching on, a ukulele for picking on, film cameras, digital cameras, a framed photo of Picasso, lights and lamps, easels and filing cabinets, trinkets, statuettes, and a number plate that spells out the word GONZO. "Some people think my studio is untidy," he says, "but I think it is immaculate because I know where everything is."

No concessions, no compromises

Ralph recently illustrated the poster for Louis Theroux’s film Scientology. He did the artwork for musician Ed Harcourt’s latest album. And later this year will publish Critical Critters, the third in a trilogy of books dedicated to extinct and endangered animals, put together with filmmaker Ceri Levy.

He worked with some of the 20th century’s most notorious writers, from William Burroughs to Will Self, and illustrated editions of novels like Alice in Wonderland and Animal Farm, and books about Leonardo da Vinci and Sigmund Freud. But throughout his career, Ralph has refused to make concessions in his art.

"I never compromise," he says. "We can discuss things, but I end up doing what I do, which I cannot help. I prefer my own projects, but I like the ideas and fun that come out of a collaboration. That’s why, when a collaboration works, you just keep on wanting to do things with that person. It’s fun with Ceri Levy. It was fun – sometimes dangerous – but always fun with Hunter."

The last time I speak to Ralph it’s by email, through his daughter, because he’s unwell. He’s 80 now and sometimes wonders if he’s done too much work. "I start to look upon it as pollution," he says. "But, at the same time, I can’t stop. I don’t know what else I’d do. I have no desire to become a racing driver." He collaborated with Thompson until the latter’s suicide in 2005, aged 67. He thinks that, were he around today, Thompson would be an important voice.

Ralph Steadman certainly is. His political cartoons have lost none of their vitality, none of their venom. You only need mention the name Donald Trump to get him going again. "He disturbs me and I feel I have to do something about him. I found the perfect idea. It has not been used yet … Keep it going, as I say to people. Keep it going. Don’t stop the immense dream. Dangerous, dangerous …"

This article originally appeared in Paint & Draw issue 8. Buy it here.

Related articles:

Gary Evans is a freelance journalist and travel writer. He is a former staff writer for Creative Bloq, ImagineFX, 3D World, and other Future Plc titles.