The secrets to becoming a successful street artist

We talk to the urban artists who are turning run-down cityscapes into grandiose galleries.

In the past few decades we've seen street art turn from vandalism to business as big. Banksy's politically conscious stencils helped propel the anonymous artist into the same pop art circles as the likes of Damien Hirst and Tracey Emin, while Shepard Fairey's street art became the defining image of Barack Obama's presidential campaign.

Win clients & work smarter with our FREE ebook: get it now!

Street art has been given the legitimacy it's always needed, and it's become a more complex, detailed medium. Cities have let artists loose on entire blocks, transforming them from unsightly grey concrete into explosions of colour and character.

It's created new canvases on a previously unimaginable scale, and digital designs are playing a huge part in the way artists design and execute their works.

A competitive business

"I use a combination of methods to create the composition and reference that I paint from," says David 'Meggs' Hooke, a sci-fi and fantasy aficionado who's created work around the world for clients such as Nike and Stüssy.

"I use Photoshop or Illustrator to compose a design by experimenting with a combination of my illustrations, sourced images and reference photos. Once I'm happy with the composition, I use it as a guide to paint from, adding colour, texture and abstract elements intuitively over the painting process."

The popularity of the medium, combined with its accessibility and the relative sparsity of available surfaces, means that street art is a competitive business, though. "I don't think it's come easily for me, ever," says David. "It's a damn lot of hard work and pressure to survive in the street art game.

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

"The majority of commissions have come to me, rather than the other way around, but I feel that it's a result of consistently working hard, painting hard, networking, and being open to opportunities to keep the ball rolling."

David still gets a thrill from creating his work. "It gives me a feeling of satisfaction to execute something and have it reflect my intentions, where the end product is what I envisioned," he explains.

Pop-out art

While street art and more conventional forms have much in common, there's another important aspect urban artists have to consider: location.

Choosing the right piece for the right place can add meaning and substance to a work, and working in particular geographic or architectural features can make it come to life. Portuguese street artist Sergio Odeith has nailed this approach.

His anamorphic pieces appear to pop out of corners and levitate above the ground, but they're cleverly rendered illusions rather than chrome sculptures.

It's all the more impressive considering his lack of formal training – another benefit of the open nature of street art. "I started painting in streets from the first time I saw a piece of graffiti," he says. "I left school at the age of 15 years old and I never went to art school."

Sergio's work demonstrates a mastery of perspective and shading combined with a blurring of the lines of reality in his blending of physical objects with painted ones. Like many street artists, he improvises additional details on the spot.

"Sometimes I do freestyle, sometimes I use computers, and sometimes I use pencils," he says. "There's not a rule or a proper software."

And this is one of the most appealing parts of street art: it's not subject to the same rigid genre and media classifications that sometimes staunchly inhibit conventional artists. All that matters is the end result, not whether it was created using oils or acrylics or Photoshop.

Urban gallery space

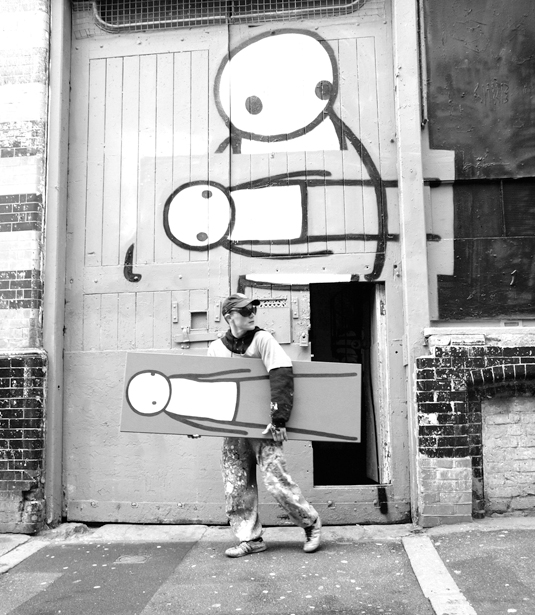

Graffiti artist Stik, whose distinctive stick figures have adorned structures around the world, was attracted to street art for its analogue nature in a sea of digital art.

"A decade ago it seemed everyone was starting to use the internet to share their art with the world," he says. "I have learning difficulties and the way that computers are designed meant I wasn't able to join in the party. The street became my website and I have millions of hits a day."

Stik's pushing boundaries in terms of how and where street art can be created. His piece Big Mother on the side of the 125 foot Charles Hocking House in London has been declared the tallest in the UK, and he's also decorated wind turbines on a Norwegian island. His relatively simple style makes it easy to create art on such an epic scale.

"I draw freehand without the use of grids," he says. "On Big Mother I used an industrial paint compressor, which gave me enough range to create five-metre brushstrokes. It's not that different to drawing small, except my arms really ache afterwards!"

While street art has evolved its own visual language and motifs, there's definitely room for more conventional artists to join the party, and it's just screaming out for some massive fantasy or sci-fi art.

Next time you fire up Photoshop, consider what your piece would look like on the side of a skyscraper.

This article first appeared in ImagineFX magazine issue 119.

Like this? Read these!

- 5 things art directors hate

- Make 3D prints using your own photos for free

- The art book that gives artists a piece of the pie

The Creative Bloq team is made up of a group of art and design enthusiasts, and has changed and evolved since Creative Bloq began back in 2012. The current website team consists of eight full-time members of staff: Editor Georgia Coggan, Deputy Editor Rosie Hilder, Ecommerce Editor Beren Neale, Senior News Editor Daniel Piper, Editor, Digital Art and 3D Ian Dean, Tech Reviews Editor Erlingur Einarsson, Ecommerce Writer Beth Nicholls and Staff Writer Natalie Fear, as well as a roster of freelancers from around the world. The ImagineFX magazine team also pitch in, ensuring that content from leading digital art publication ImagineFX is represented on Creative Bloq.