Why designers should give branding back its soul

In an age where companies think branding strategists can solve all their problems, Adrian Shaughnessy argues that designers should take back control.

Graphic designers rarely question the practice or culture of branding. Hardly surprising, since the creation of brand identities and branded communications is what provides so many graphic designers with a living. Designers need clients, and clients want branding. Vast swathes of the public love brands, and we live in a world where everything and everyone from Premiership football clubs to former Big Brother contestants think of themselves as brands.

So, if designers want to have plenty of work, it's probably wise not to look too closely at what branding is, and what its effects are on the profession of design or on the wider culture. However, this unquestioning assimilation of brand culture is inevitably raising questions of its own.

For example, why have hundreds of designers chosen to call themselves 'brand designers', or even worse, 'brand imagineers'? And why has the term 'identity designer' been widely abandoned, when it more accurately - and perhaps more honestly - describes what the majority of 'brand designers' actually do?

Opposition to branding

Of course, beyond the world of design it is not the case that everyone accepts branding unreservedly. There are those, such as anti-capitalist activists, who are opposed to branding in all its forms and see it as a representation of unacceptable corporate power. There are also social commentators and cultural thinkers who see our obsession with brands as evidence of enslavement to materialism and consumption.

Even within the design profession there is a small coterie of designers opposed to the cult of branding. This is usually for ethical or political reasons (fashion brands that use sweatshops in the developing world, or political objections to institutions such as the Fox Broadcasting Company, for example). But it is not my intention here to discuss the ethical or political sides of branding.

Instead, I want to look at three things: the ways in which branding has affected the practice of graphic design and the role of the graphic designer over the past few decades, the reasons behind why graphic designers gave up being 'identity designers' in favour of becoming 'brand designers', and what exactly constitutes good and bad branding.

Branding: a definition

First, we need a clear definition of what branding actually is. In the graphic design section of the website About.com, the following definition is offered: "To create a 'brand' for a company is to create their image, and to promote that image with campaigns and visuals.

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

"Working in branding allows a graphic designer or design firm to get involved with many aspects of the industry, from logo design to advertising to copywriting and slogans. The goal of a brand is to make a company unique and recognisable, and to project a desired image."

A more nuanced definition is provided by Seth Godin, an author and entrepreneur who has been lauded as America's greatest marketer. For Godin, a brand is "the set of expectations, memories, stories and relationships that, taken together, account for a consumer's decision to choose one product or service over another".

Godin also goes on to make the point that a brand "used to be a logo or a design or a wrapper. Today, that's a shadow of the brand, something that might mark the brand's existence. But just as it takes more than a hat to be a cowboy, it takes more than a designer prattling on about texture to make a brand." He concludes by stating that, in brand creation, "design is essential, but design is not brand."

Facile reduction?

A less sympathetic description comes from business writer Lucas Conley in his book Obsessive Branding Disorder. "More than marketing, more than advertising, or positioning, branding is an all-in-one ideology - a facile reduction malleable enough to govern all facets of modern business. In the name of the brand, any idea can be defended as valid and any crackpot can assume the status of a guru." It's clear from this short statement that Conley is not a fan of branding 'ideology'.

My personal view is that the role of design in branding is about the creation of the symbolic or outward face of companies, institutions and services. But as soon as branding becomes about depicting or conveying the less tangible assets such as 'brand essence', 'brand promise', or any of the other clichés of branding, I become skeptical about what designers can contribute.

Anyway, telling customers what to think in the age of social media is simply a waste of time. Not only that, it's also a form of fundamentalism.

The brand effect

As Seth Godin makes clear, brand people love to proclaim that a brand isn't just a logo. And if you are looking at the total footprint of a brand, then that's absolutely true. But try building a brand without a logo or graphic architecture, and you'll find that it simply cannot be done.

So whether the brand gurus like it or not, the logo is still king in the world of branding, which in turn prompts the question, why are so many brand theorists in such a rush to downgrade the importance of logos and design in general? Remember Godin's phrase - "it takes more than a designer prattling on about texture to make a brand". Unless I'm very much mistaken, there's a strong hint of anti-designer sentiment there.

If we accept that the 'design' - the logo, graphic architecture, and so on - is the badge of recognition and the point of identification for all brands, then we must also acknowledge that designers are pretty important factors in the making of brands - perhaps more important than any other individual or group in the entire brand creation process.

If this is true, then it puts a great deal of power directly into the hands of the designers.

And here's where the problem lies: designers are notoriously tricky and mercurial characters. They're difficult to control and stubborn about their ideas. As far as the brand consultants, the marketing people and the PR busybodies are concerned, life would be much easier if it could be proved that design is only a minor part of brand building, and much better if non-designers were in control of it.

By making branding into something other than a graphic design discipline, clients have leveraged control of design away from designers and into the hands of various non-designers. You can see this most clearly in the big branding groups, who employ dozens of 'suits' - strategists, business analysts, account handlers - and only a tiny number of designers.

Control issues

The most significant effect of this is to hand control of branding to brand people, and to be a brand person, you don't need to be a designer. Business people understand branding in a way that they don't understand graphic design.

They become obsessed with strategy, values, tone of voice and market research, forgetting that they are judged on their products, their services and their conduct, and not on what they say (or think) about themselves. In other words, businesses imagine that they can brand their way to success - which of course is an illusion.

Apple products are loved because they work efficiently and look good - and it's this that forms the public's opinion. If we look closely at what Apple does in other areas of its business (tax affairs, factory conditions, endless patent squabbles) it becomes much less attractive.

Which really takes us to the heart of what branding has become: hype and spin. We've all been driven mad by banks that profess to be customer-centric and spout mantras such as "always giving you extra", and "we like to say yes", but then fail spectacularly to live up to those claims.

Kafka-esque hell

Think of all those companies that offer to put us - the customers - at the heart of what they do, but when we actually need them to sort out a problem, require us to descend into a Kafka-esque hell of telephone help lines, corporate indifference and computerised systems designed to make life easy for the business owners, not the customers.

There are two major side-effects to allowing non-designers to control branding. The first is to allow logos and design language to emerge that are poor, or in some cases dire, in appearance. The second is that, by allying themselves with the gobbledegook of branding, designers have allowed design to become a junior partner in the brand creation process.

The consequence of this is that most branding programmes are run by non-designers, with predictably bland results.

The decline of the identity designer

In our always-on, networked world, no business or institution can be unconcerned about its public image or its reputation. No one denies that managing a brand's ecosystem is important and necessary, but without a good visual thumbprint, without good identification collateral, this task is impossible.

So when I say that I think it was a mistake that designers stopped being identity designers and became brand designers, I'm not being backward-looking. Instead, I'm saying that it is more progressive to be concerned with the visual image of an entity than it is to be concerned with its 'brand values', which in the end are mostly just smoke and mirrors.

Plus, and this is the really important bit, the other stuff is no longer controllable. Firms and organisations can say that they are 'ethical', 'customer centric' or 'service focused', but unless they really are these things, they are wasting their time saying that they are. For me, this is why designers should stick to design, and firms should not confuse branding with the actual services or products they offer.

Keeping it simple

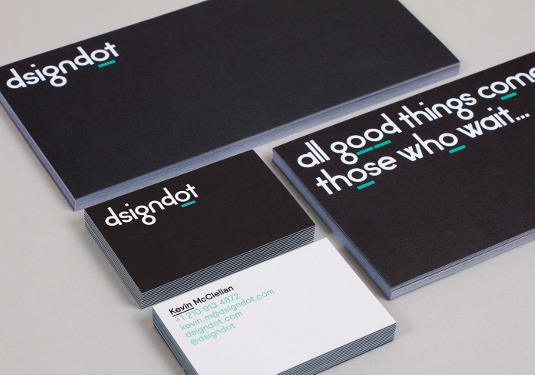

The designer Sean Perkins founded North, one of the most admired design studios of the past 20 years. The company has created groundbreaking identities for RAC, First Direct, the Barbican and The Photographer's Gallery. Its work is always robust, distinctive and highly attuned to its client's needs. But Perkins is adamant that he is an identity designer, not a brand designer.

For him, identity is "building the essential elements that an organisation is known by: name, logo or symbol, colour, typographic style and visual language, and how you uniquely put these together, how you express these to create a sign, an image. We create the building bricks of an organisation's DNA."

Perkins sees a clear difference between brand creation and identity design: "The brand is the whole experience, the service, product, personality and expression, and I can't see how people claim to do the branding, the total experience. We build identities, not brands."

He also sees a clear difference between North and conventional brand agencies: "We are different because we are probably a bit old fashioned; we believe in strong, honest, uncomplicated communications, usually minimal symbols and trust marks. We keep it simple." Far from being old fashioned, Perkins has recognised that the greatest service a designer can offer to an organisation is clarity and integrity of image.

In Perkins' view, Vitra, Mercedes, Audi, Apple and Lufthansa all have great brand identities. He calls them "timeless, and no matter what the climate, consistently strong". But significantly, all these identities were initially created before branding replaced corporate identity as the primary activity of many designers.

What makes a good brand identity

Good visual branding is honest, graphically expressive and highly memorable. It should be optically sophisticated (not muddled or over-cooked) and it should work in print, digital and broadcast settings. In other words, what Sean Perkins calls "a strong, simple identifier that can imbue subliminal qualities of strength, security, trust and assurance".

In truth, making a clear visual statement and incorporating some subliminal messaging is really all that a brand identity can hope to do. Any ambition beyond that is simply wishful thinking.

Take the Google logo. It is cheerful, and people seem to like it, especially the way it is allowed to reflect events and anniversaries. It has been created for the digital era - a near zero-weight logotype designed for fast loading. But I can't help thinking that its cheerfulness is designed to mask the darker aspects of Google's activities. I don't think that Google is evil, but it is unavoidably involved in aspects of digital culture, mainly relating to privacy, that cause concern.

However, my main objection to the logo is that it is a piece of woeful logotype design for one of the most ubiquitous companies, and it could only have emerged in the age of branding. It's impossible to imagine any of the great logo designers, dead or alive, doing anything as weak and lacking in subliminal qualities. Yet for the age of branding, it is somehow acceptable.

Brand value must be earned

I want to end with a plea for a return to smart identity design. To try to achieve anything else is almost pointless, and will also involve the designer - and brand owners and consultants - making horrendous assumptions and arrogant assertions.

For me, all the brand identities that work are memorable, optically robust, and designed with a sense of style and proportion. These are technical qualities that can be evaluated and assessed, but I also look for how well a brand identity is suited to the entity it is serving - the subliminal qualities that Sean Perkins mentioned. Yet I suspect that in nearly all cases these are retrofitted.

We imbue the logos and physical appearance of a brand with the values that we want. In other words, business and institutions have to earn brand value - it simply cannot be imposed by a logo, a slogan or a promise. It has to be real.

Words: Adrian Shaughnessy

The graphic designer, writer and educator is a co-founder of Unit Editions, and has written, designed and art directed numerous books on design. He has been interviewed frequently on television and radio, and lectures extensively around the world. He is a senior tutor in graphic design at the Royal College of Art in London.

This article originally appeared in Computer Arts issue 219.

Liked this? Read these!

- The ultimate guide to logo design

- Discover the world's top brands - and why they work

- Where to find logo design inspiration

Do designers need to take back branding? Tell us in the comments!

Thank you for reading 5 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

The Creative Bloq team is made up of a group of art and design enthusiasts, and has changed and evolved since Creative Bloq began back in 2012. The current website team consists of eight full-time members of staff: Editor Georgia Coggan, Deputy Editor Rosie Hilder, Ecommerce Editor Beren Neale, Senior News Editor Daniel Piper, Editor, Digital Art and 3D Ian Dean, Tech Reviews Editor Erlingur Einarsson, Ecommerce Writer Beth Nicholls and Staff Writer Natalie Fear, as well as a roster of freelancers from around the world. The ImagineFX magazine team also pitch in, ensuring that content from leading digital art publication ImagineFX is represented on Creative Bloq.