50 tips that will make you a better illustrator

Daniel Stolle shares pearls of wisdom gathered from 10 years of illustrating.

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Five times a week

CreativeBloq

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Once a week

By Design

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Once a week

State of the Art

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Seasonal (around events)

Brand Impact Awards

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

After 10 years working as an illustrator, I've compiled 50 pearls of wisdom to help fellow illustrators. For a while I've been thinking about what I've learned on that journey, and how I can communicate it. I'm not a writer, so like with many other things, I needed to find a way of working first.

For more than half a year I jotted down my thoughts as one-liners while working on illustration jobs. I collected a list, covering a range of facts, simple observations, bold statements and hyperbole.

In the following 50 tips, I offer seven steps of in-depth advice first, followed by 43 quickfire thoughts, tips and tricks on the next page.

As with all in life, take these – my subjective views on life as an illustrator – with a grain of salt. May they be of help on your own journey.

01. Forget style

In the illustration world, especially among young illustrators, people seem obsessed with talking about style – how to find a style, whether they should have more than one style, and so on.

It has been said countless times, but I'll say it again: Just work and your 'style' will emerge (see how I can't help but use the word with inverted commas). Steadily working and observing your own drawings will help you to discover things in them that could be the seed for a whole body of work.

If you are obsessed by somebody else's work, try copying it as an exercise (do not present it as your own, though). In that process, you will notice what suits you and what does not. I found doing such an exercise so tedious that it sent me running back to my own stuff very quickly.

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

When working on an actual job, style is rarely a topic of conversation. I very seldom receive older images of mine as a reference for what is expected of me. My 'style' (I cringed a bit when writing that) has broadened nicely over recent years. Clients often even give me complete trust and thus freedom to choose what I think will work best.

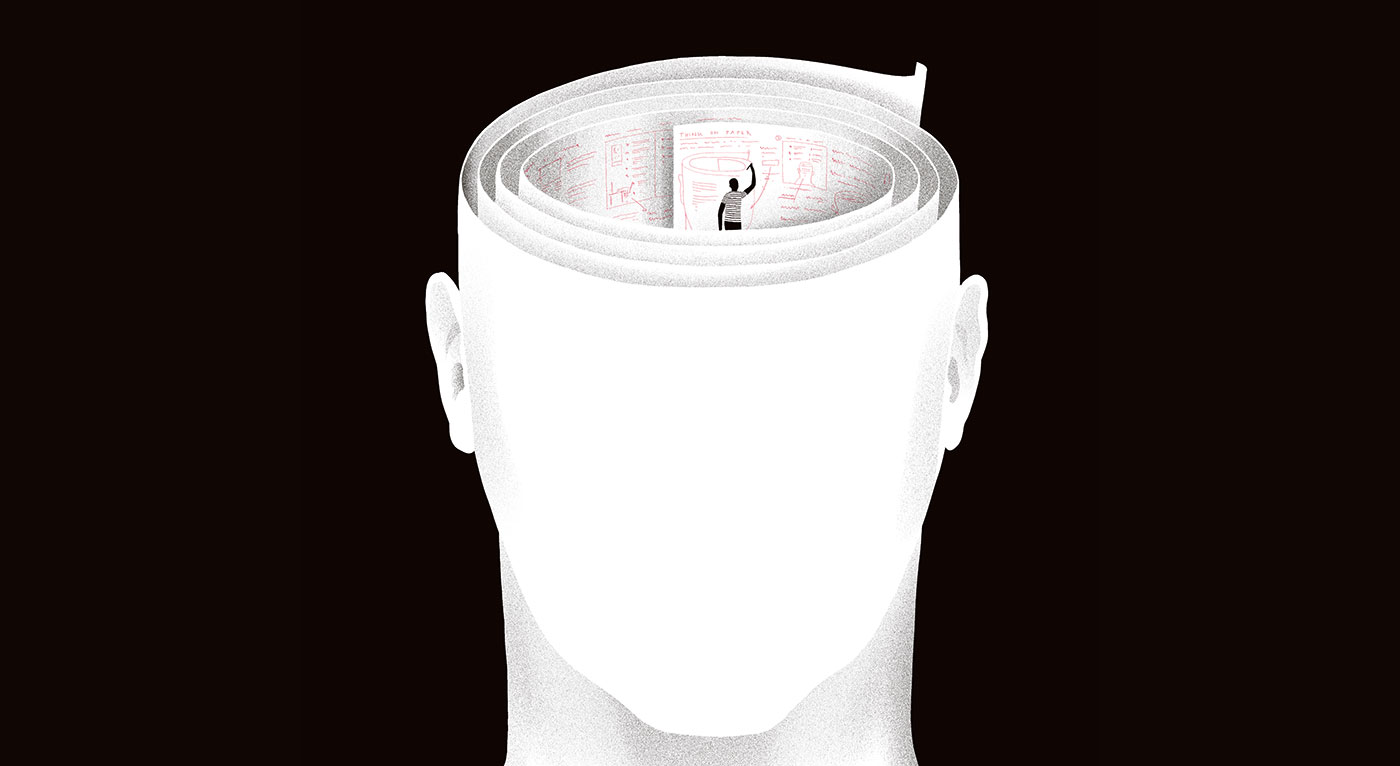

02. Use paper

Digital methods of creation have undoubtedly become indispensable for communication and allow us to be immensely effective when finalising our work. But let's be honest: we cannot think on the screen yet.

I've noticed that with a piece of paper in front of me, my sense of composition comes more naturally than it does on a screen. My hands and eyes are interacting with the area of the paper and measuring distances constantly. When sketching on the computer, I find that placing everything correctly requires a lot more tweaking. It is harder to keep a sense of the bigger picture when working digitally.

Similarly, I also tried writing with a fountain pen and noticed how words and sentences started to flow out, like ink, naturally onto the paper. Thoughts formed easier than when I was typing on a keyboard.

Paper is one of the oldest technologies we have. Cultural creation has been based on it for millennia. Let's not abandon it just yet, especially in the early stages of a project.

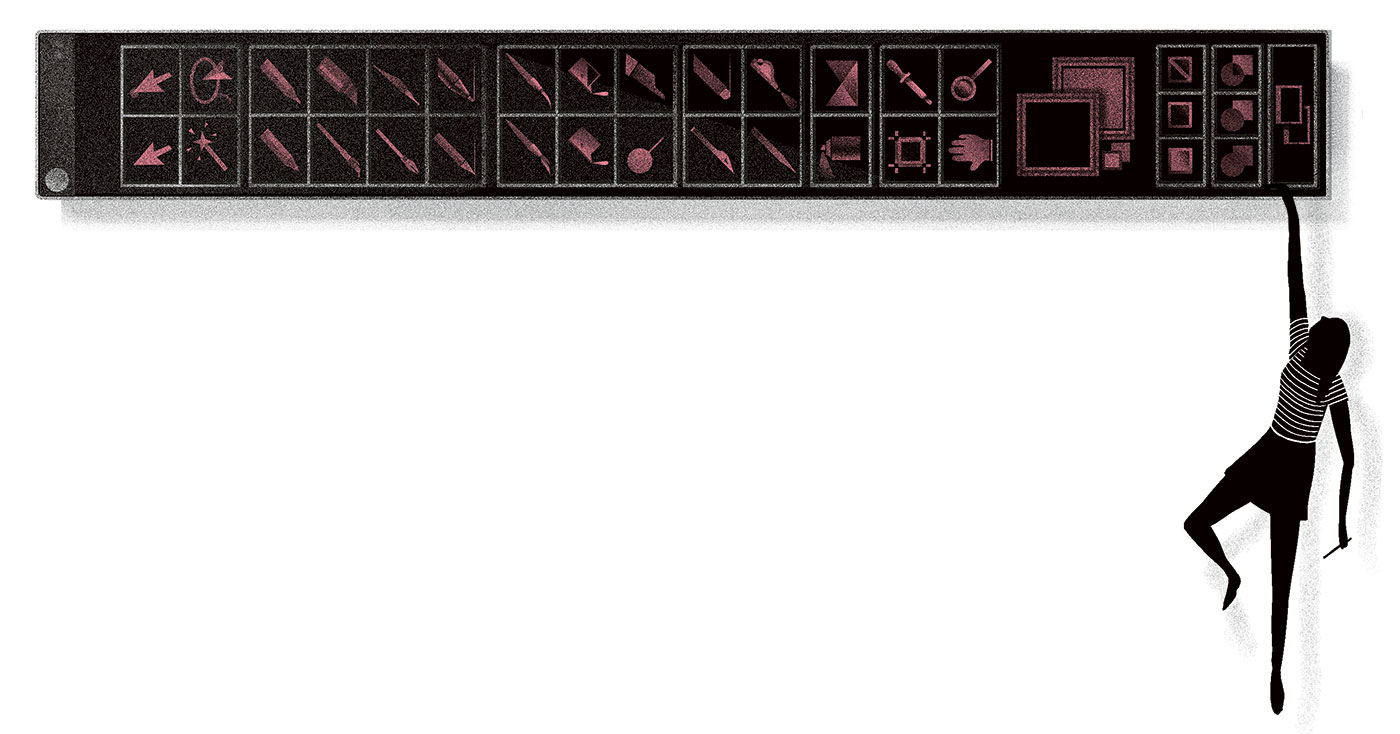

03. Remember that digital tools aren't magical

New software versions, texture packs, Photoshop brushes, Wacom tablets, iPads and Apple pencils are the tools of our trade. Even when working in analogue, it is almost impossible to steer clear of digital tools entirely. And while a tool can be motivating for a while, it is too easy to get obsessed by a constant need for the new.

I think the problem is the way that we approach these tools as if they have magical properties. We imagine ourselves working with the tool in scenarios that are not realistic, and often do not reflect our actual way of working. For example, take the idea that if I only had that new iPad Pro, I would go out and make on-location drawings. But if I have never done an on-location drawing before in my life, the iPad will probably not get me to do it.

Apply some sobriety to your kit wishlist – are the items on it actual needs or just wants? Ask yourself which of the tools that you already own have really had an impact on your work, to help you decide.

Digital tools usually develop incrementally. So it's not often that a revolutionary product or software feature comes along that improves our way of working dramatically. Therefore, don't expect wonders from a new digital tool any more than you would expect any huge transformations from a new pencil.

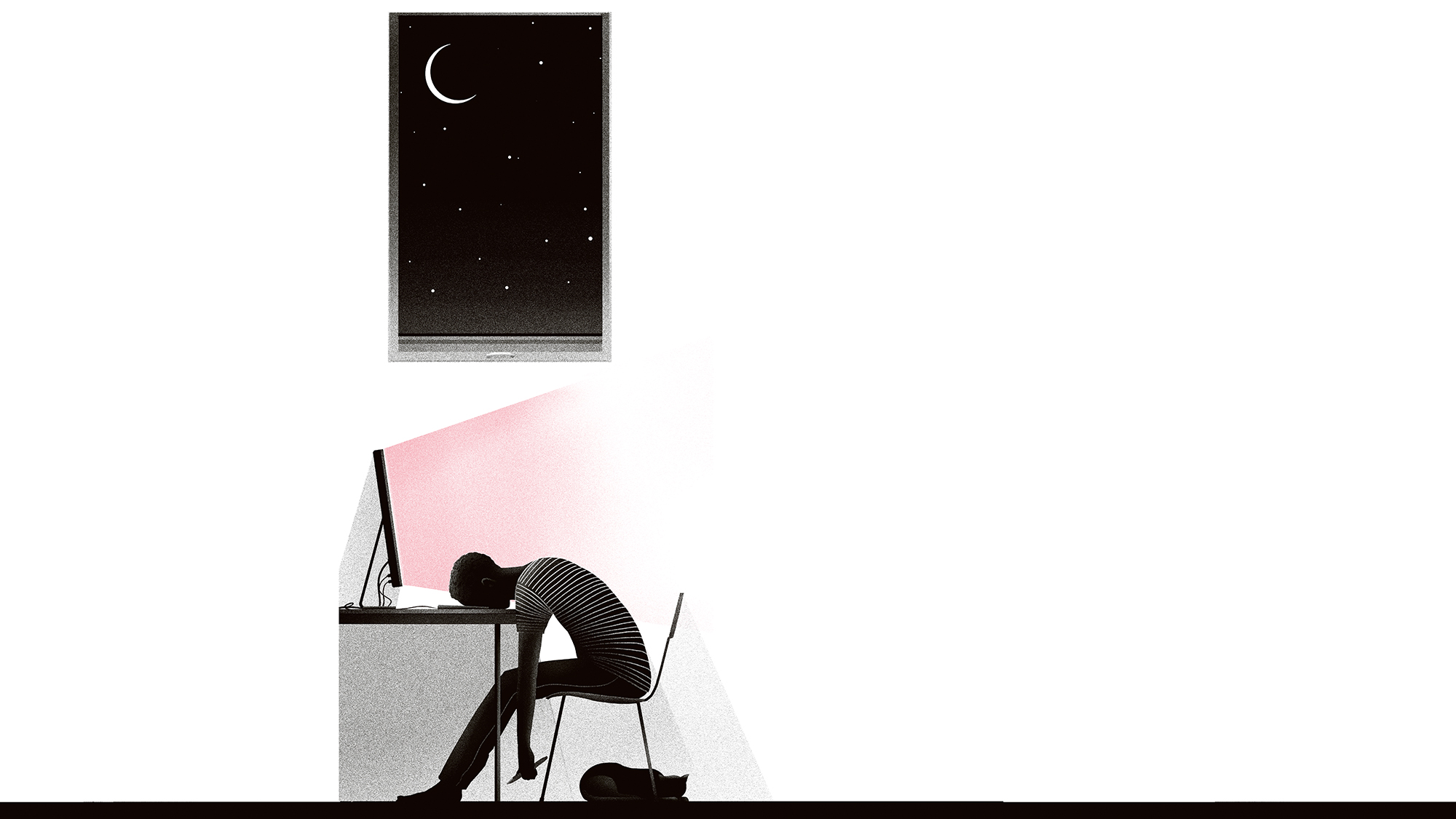

04. Be realistic about time

It is easy to make unreasonable assumptions about what you can achieve in one day. For example, having the idea that: "If only I hunker down properly today, I could finish the whole project." The end of the day will inevitably roll around and crush your plans. Nobody can really work for a full eight hours every day intellectually. It is impossible to stay focused and to concentrate on pushing a project forward in a meaningful way for such a long time.

Many novelists do not write for more than four hours a day. A move to a six-hour working day in some Swedish companies even showed an increase in productivity. The way you think you are working is probably not congruent with the way you are actually working (see tip 22). We are constantly frustrated by our progress, while at the same time, we are – with a little discipline – remarkably consistent in our output. Why not accept reality and use it to our advantage? Plan more realistically to be less frustrated.

Time can also be on your side. Looking at your work again tomorrow, instead of rushing it out today, will give you a more objective look and maybe even provide the chance to make the final tweak to push a drawing from good to great.

05. Don't steal other people's ideas

I don't think copying ideas has a place in illustration. I pride myself on coming up with the right image, and thus the right idea for a given text. If nothing else, that is what separates me from stock art. And in times of a large, aware online public, it also seems foolish to steal ideas and not expect to be found out.

That being said, I'm convinced that you can copy an idea entirely by accident or subconsciously. For each final illustration I make, I provide two or three (hopefully) original ideas. That amounts to me generating several hundred ideas per year. The numbers are high. As illustrators, our personal and professional backgrounds are often similar, so the symbols and references we have in our minds may also be similar. I think that having the same ideas is inevitable at times, however unlikely a mere coincidence seems at first glance. So please reflect on your outrage the next time it happens.

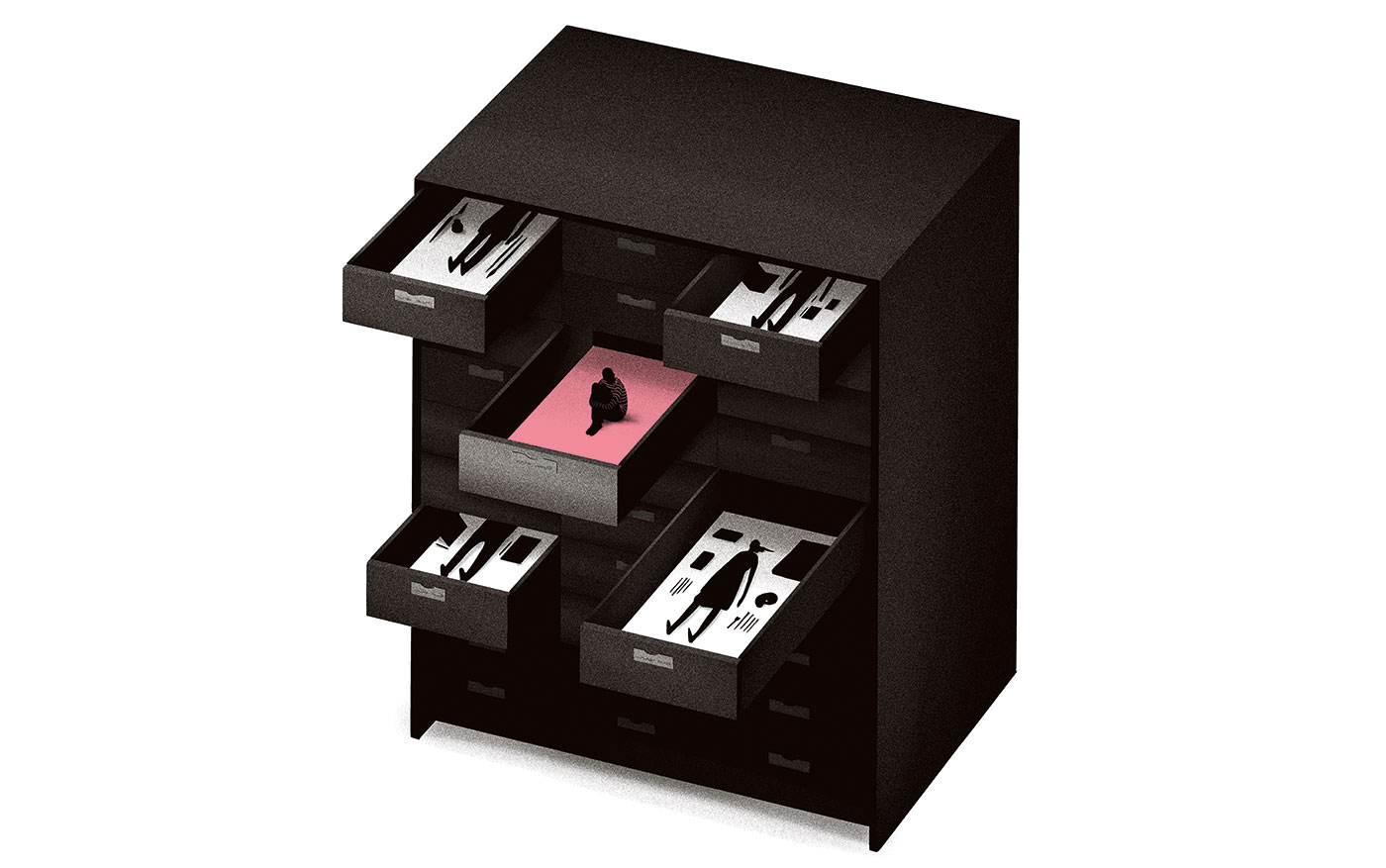

06. Know that big clients come with big hierarchies

When graphic designer Kurt Weidemann redesigned the logo of German railway Deutsche Bahn in the early '90s, there was uproar in the press because he received a record fee of 200,000DM (about £152,000 in today's money) for his design services.

For this fee, however, Weidemann had spent endless hours explaining his work to mid-level executives, and sat in many mind-numbing corporate meetings. He also got a lot of flak from the media when the design was finally revealed.

On the surface, making an editorial drawing and one to be used in an advertising campaign is not that different. The higher fee for ad jobs is justified by the client buying a more comprehensive license. Where is the problem?

Here it is: When working on ad jobs, you are usually working opposite a team of people in various positions, who are in turn responsible to a team representing the client. The result is that you are facing a hierarchy – or even two hierarchies – who all have a say on the outcome of what you are drawing. The result is a strictly controlled environment, and that means many revisions before everybody is happy.

Like Weidemann, you are faced with a corporate machine. Unlike Weidemann, you might not have enough standing (or stamina) to protect the integrity of your work until the finish line. That is what you are compensated for.

07. Know thyself

While you're studying illustration – either formally, or by yourself – you are exposed to great work by others. You feel jealous of your peers and in awe of the masters. You're inspired, you're confused, you try to create, and then you're frustrated by what you produce and how badly it compares. And in spite of it all, you're still driven to make something, so you try again.

Although you are dealing a lot with your emotions in that whole turbulent process, you might not have learned to observe yourself and what you are doing yet. To be successful, you need to find out a lot of things about yourself first: What are your strengths? What are your weaknesses?

This is easier said than done, but start with simple things first. For example, what are your most productive working hours? Whether you work best at 6am or midnight, don't miss out on these hours, and try to plan the rest of your day around them.

Once your needs are taken care of, you will become less anxious. You are the person you have to work with for the rest of your life, so get to know yourself. Be disciplined, of course, but also be accepting and tolerant.

Next page: Quickfire tips and tricks for illustrators

- 1

- 2

Current page: 7 detailed tips for illustrators

Next Page Quickfire tips and tricks for illustrators