The art of innovation

Design innovation can take many forms, argues Frog's Andreas Markdalen – but it all starts with asking the right questions.

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

There's an old episode of Blue Peter, the classic BBC kids' show, where children around the UK are invited to submit their redesigns of the generic lunch box. In a rare cameo, Sir Jonathan Ive is asked about the most common mistake when redesigning an icon like this. His answer is that participants often make the error of taking the name too literally, and start thinking of a new, improved box for their solution.

The true innovators are those who think outside of the box, in every sense. These people will conceive a new type of lunch container altogether - a new form or idea that disrupts the perception of the product.

The Blue Peter episode, and Ive's comment, made me think about the current state of design and the special relationship that we, the designers, have to the artefacts we produce in our daily work.

Consider this for a moment: we define our craft and promote our work through artefacts. We tell stories using artefacts. We see beauty and timelessness in artefacts - we understand them and feel them. Well designed artefacts appeal to us. They make sense.

As designers, artefacts define us. We were educated to look at design in this way, responding to the immediate impact of the thing in front of us: to see it, feel it and react to it. This education shaped our methodologies, our processes and ultimately our craft. It made us fluent in creating things of beauty - things that you could hang on your wall, study or admire. We learned to love stuff that would inspire us, transcend the trends and deliver a strong message - artefacts that would leave a mark in time. That was the mould that shaped our way of thinking about design, our belief systems.

A new world

Then, one day, we awoke to a New World Order. The interaction design work that we had been playing around with on the side of other projects wasn't just another new thing to do, it was the only thing. It was the future.

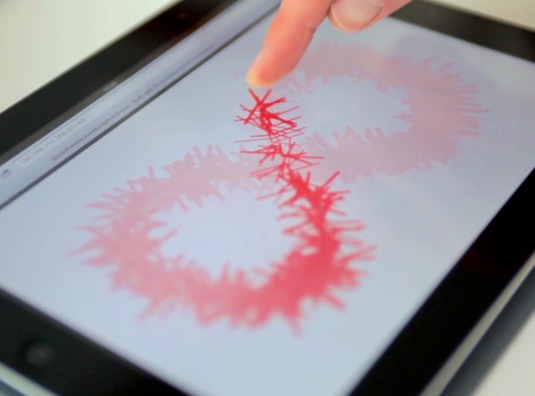

We realised at this point that we weren't designing to communicate any longer; that our work wasn't designed to be passively digested or admired. It was to be interacted with. We realised that we weren't just designing the tangible artefacts to hold onto and touch, but also the invisible connections in between them - the connections between systems, objects and human beings. As designers of interactions, we were orchestrating those connections, the moments in between, the anti-matter of human habits and routines. And it blew our minds.

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

It quickly became obvious that we had only been looking at design through one fragmented perspective - that one singular lens we were brought up with; that designer-as-genius, Paul Rand-esque, waterfall model way of working, which now seemed so disconnected from what we were experiencing within our daily work. It shook us up. We were un-learning.

Blurring the lines

Disciplines are converging, and the kind of user-centric approach that has long been the heartland of industrial designers is becoming increasingly relevant within branding agencies too. "The product world has always measured impact through customer experience," reflects Neil Cummings, creative director at Wolff Olins London. "A focus on experience forces us to look broader, dig deeper, get closer to customers and add furiously to the disciplines that have traditionally made up branding."

For Cummings, the days of the celebratory launch of a branding scheme are all but numbered: "It used to be seen as the fantastic fireworks show at the end of a long branding project. In truth, it's only the starting pistol. The hard work starts now."

Although the cornerstones of branding - creating purpose, standout and consistency - are still front-and-centre in the company's aims, at Wolff Olins the process must go beyond that. "It's the catalyst, the engine, the connective tissue for beautiful experiences," continues Cummings.

Innovation, he points out, is blurry by nature. "It doesn't have any clearly defined edges, and this is fantastic for the design industry," he explains. "Previously distinct, siloed disciplines are being drawn slowly towards a centre of gravity."

All this has a knock-on effect. As branding agencies become fascinated by customer experience, innovation agencies become increasingly aware that the products they develop start conversations about branding. "All of this movement is in service of one thing - the user or customer," Cummings concludes. "The victors will be those who can prove their value to those at street level."

Thinking through making

Of course, the beauty of innovation is that there's no one-size-fits-all approach. For an agency such as Berg, creator of the much-loved Little Printer device, Twitter-connected cuckoo clock #Flock, and most recently smart washing machine Cloudwash, human-centred design takes a back seat. Instead, the company favours technological experimentation as part of its 'thinking through making' approach.

"The grain of technology reveals a lot about what will work and be satisfying, and what won't," reflects Berg co-founder Jack Schulze. "In this way, we are not human-centred at all: we're technology, business, software and system-centred. We don't begin by trying to solve 'real problems' - we look opportunistically at the technology around and stitch things together out of that."

At the forefront of the so-called 'Internet of Things', Berg specialises in bridging the gap between familiar physical artefacts and the digital, interactive world. "The behaviours in these objects are as important as their material quality or their formal industrial design," he continues. "Certain sorts of behaviours are now possible for objects and messages that were previously unthinkable."

To illustrate his point, Schulze gives the examples of a Kindle - which holds almost no value without Amazon's software back-end - and even more extreme, Apple's iPod Shuffle. "It literally doesn't have enough buttons on its surface to function without the iTunes infrastructure," he says.

A new type of challenge

As the world continues to evolve all around us, off ering countless new contexts, possibilities and issues to be dealt with as designers - with new technologies to explore - we are still absorbed with the production of artefacts. Our focus remains on the things that we design and the process we undertake to create them; the 'what' and the 'how' of design. The greatest challenge for the next generation of designers, then, is to go beyond the artefact and start asking the right questions.

"The most recent thing I've started doing is seriously thinking about process," reveals Cummings. "Thinking carefully about how to design the conditions that will lead to the right type of outcome."

Wolff Olins approaches innovation as neither an activity nor an outcome: "It's something hard-coded. Cultural. Deep in the tissue of business, because it's in the blood of the people that work there," Cummings declares. "At its best, it exists naturally, within normal processes. It's not the preserve of the boffin or the wizard. It's a disruptive spirit that forces us to ask how everything can be better. It's good, bold design."

The creation of problems

Although some kind of 'artefact' is invariably produced at the end, at Wolff Olins it's the process - or the disruption of it - that lies at the core of true innovation. "It's about going against the usual way; redesigning a project for a short while to see what pops out," smiles Cummings.

"Of course you're often asking a lot from a client to do this - especially if there's no defined deliverable, no surety that what comes out will be any good and no concrete idea of what 'good' even looks like," he admits. "Sometimes you just have to go 'black ops', take it offline and dazzle with the outcome."

Consider for a moment that the brief you've been given for your design project was written by a group of people; a group of client stakeholders who, of course, all have a vested interest in the output of your work. This group is likely to shape the brief through a set of needs - business needs, marketing needs, strategic needs, brand needs - that are crucial to the project's success.

The written brief will outline specific goals for measuring success and will define a number of artefacts for you to design in order to reach the outlined goals: a website, a leaflet, an intranet, a piece of signage, an app and so on. Then imagine for a moment that you are writing the brief instead; that you would be making the calls and deciding what to include. What would you ask yourself to produce?

As designers we have the capacity not only to produce the answer, but also to alter the question. These days we actually do get to write our own briefs and create our own problems to solve within predefined spaces, simply because our clients trust us to do so; because we've proven that it brings results.

Human-centric

We offer our clients a different perspective on their business. Designers don't begin by looking at financial goals or marketing needs. Instead, they focus on human needs. This is the fundamental aspect of human-centred design.

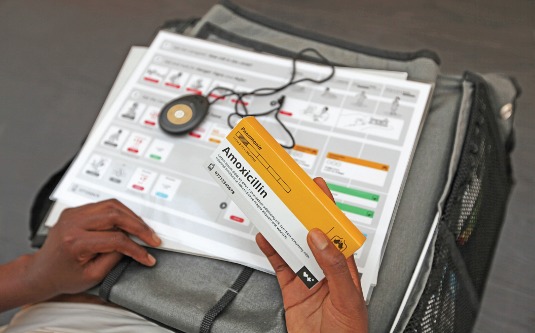

"We strive to understand the human experience and understand what human beings aspire to be," reflects Fabio Sergio, vice president of design at Frog, a global product strategy and design firm committed to innovation and improving lives through design.

"At Frog, we pride ourselves in deeply involving end users in the creative process. It's participatory: we see them as peers," continues Sergio. "It's about embracing humility, and admitting that the person you're designing for often has much more knowledge than you have," he adds.

For Sergio, if you can forsake your ego and welcome this knowledge then it's an incredible time to be a designer. "It's about proud humility: embracing the complexity of the scale of human challenges," he argues.

By doing so, designers have the opportunity to shape the future in the process. "People talk about the future being a long way away, but the future is tomorrow to the scale of 10. Whatever you design today will influence what you do in 30 to 40 years," he continues. "By throwing sticks in a river, over time you can build a dam."

Total immersion

Embedding ourselves into the cultures and environments within which we've been asked to innovate enables us to investigate and gather clues, without the bias of a predefined point of view. By studying people and experiencing their cultural and social fabric, we can get an idea of how people live their lives, how they interact with each other and what they dream about before they go to bed at night. It enables us to look beyond the numbers and create design concepts that are truly meaningful to individuals: a person with a name.

It's shaping the question that makes a diff erence. Not only looking at the what and the how, but more importantly – the who, the when, the where and the why. "Often we think design is about bringing something new into the world. Most of the time, however, it's actually about taking some idea or thing that already exists and making it better," says Anthony Deen, creative director for environments at Landor New York. "Innovation is just that: making something better."

For Deen, innovation always begins with research. "We infuse the work we do with the knowledge we obtain from that initial work," he explains. "By innovating, we make our work smarter, and we make the products of our work smarter. Smarter products are better products; better for our clients and better for the world."

Although widely known for its branding and packaging work, Landor has a strong heritage in industrial design that stretches all the way back to agency founder Walter Landor. At the core of its practice is what the agency calls 'eco-innovation' - for which it considers the environmental sustainability of any given project.

The cycles of change

"Landor integrates this requirement into our entire design process, because we believe that as designers we're responsible for the manufacturing process and for the life cycle of the products we create," explains Deen. Practically speaking, this involves thinking about what happens to the product that's being designed after its useful life is complete.

"We research best practices, and then try to exceed those parameters," he explains. "Next, we bring a multidisciplinary team in on every project. This gives us diff erent perspectives and points of view to inform the design, and numerous approaches to solving problems." It may be time-consuming, but tackling the brief from several angles leads to the confidence that the agency is innovating in the best direction.

"Be smart and be rigorous," is Deen's advice. "Always question your own work, and look for ways to continually improve it. You'll know when you get to the point where the product just can't get any better."

Outside the lunch box

Sir Jonathan Ive's comment about the lunch box can be applied to specific examples of innovation, looking at individual design projects or contexts. Yet, it's more interesting when considering our discipline in general. Does a lunch box have to be a box? Does design by rule need to come in the shape of a design artefact?

Things change. Technology will change; outdoing itself over time to be replaced tomorrow by something smarter, better and faster. Devices and platforms come and go. The older screen will be exchanged for the newer one, and we will adapt our designs to it in a heartbeat. Trends will come and go; be celebrated, then over-used, then passed over and shamed, only to be brought back again later. User interfaces were once industrial, then realistic, then flat, now whatever else; changing just as rapidly as any other commodity.

These shorter micro-level cycles of taste and 'fingerspitzengefühl' [a German term - literally 'fingertips feeling' - that refers to an innate flair or sophistication] detract from timeless values of quality and beauty, momentarily resulting in anti-design and brutality in execution. It will shock us for a while before we get bored and start over. It's all programmed in time, in the nature of how things change. And as all of this is happening, as the designers around the world are running faster and faster to chase these ephemeral variables of perceived perfection in their artefacts, one thing will always remain the same: the human condition.

Maybe that's where you should be spending your time, understanding what gives people their highs and their lows, how you can make their lives more enjoyable, or in some cases more bearable. It might just be the best thing you've ever done, and it all starts with asking the right questions.

Words: Andreas Markdalen

Design director at global product strategy and design firm Frog, Andreas is an award-winning multidisciplinary designer who has spent 10 years working in the fuzzy space that separates and connects visual design, branding and user experience. This article originally appeared in Computer Arts issue 228.

The Creative Bloq team is made up of a group of art and design enthusiasts, and has changed and evolved since Creative Bloq began back in 2012. The current website team consists of eight full-time members of staff: Editor Georgia Coggan, Deputy Editor Rosie Hilder, Ecommerce Editor Beren Neale, Senior News Editor Daniel Piper, Editor, Digital Art and 3D Ian Dean, Tech Reviews Editor Erlingur Einarsson, Ecommerce Writer Beth Nicholls and Staff Writer Natalie Fear, as well as a roster of freelancers from around the world. The ImagineFX magazine team also pitch in, ensuring that content from leading digital art publication ImagineFX is represented on Creative Bloq.