Retro-inspired shooter Birdcage feels like it's 1998 again, right down to purposeful slowdown

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Five times a week

CreativeBloq

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Once a week

By Design

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Once a week

State of the Art

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Seasonal (around events)

Brand Impact Awards

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

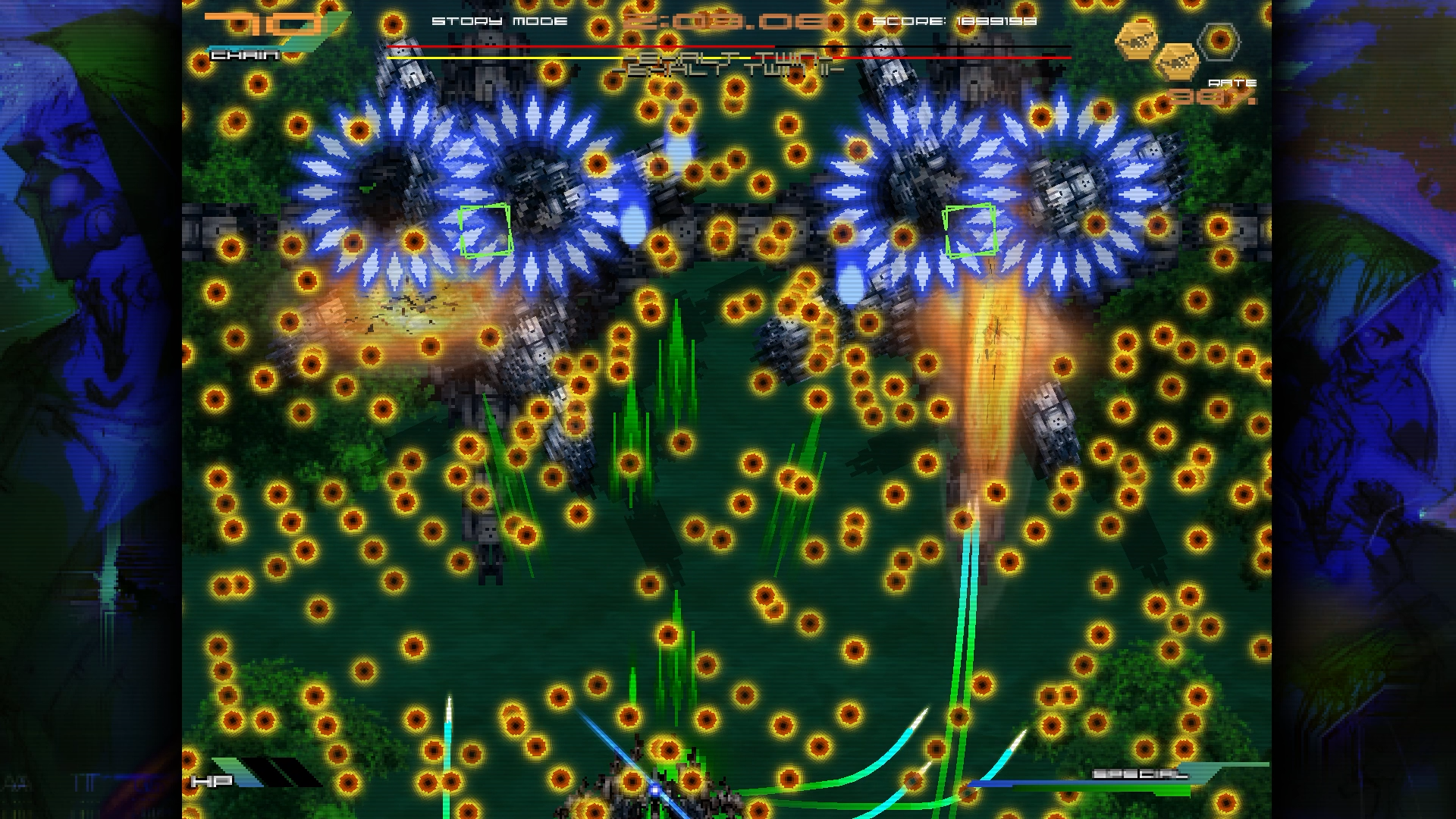

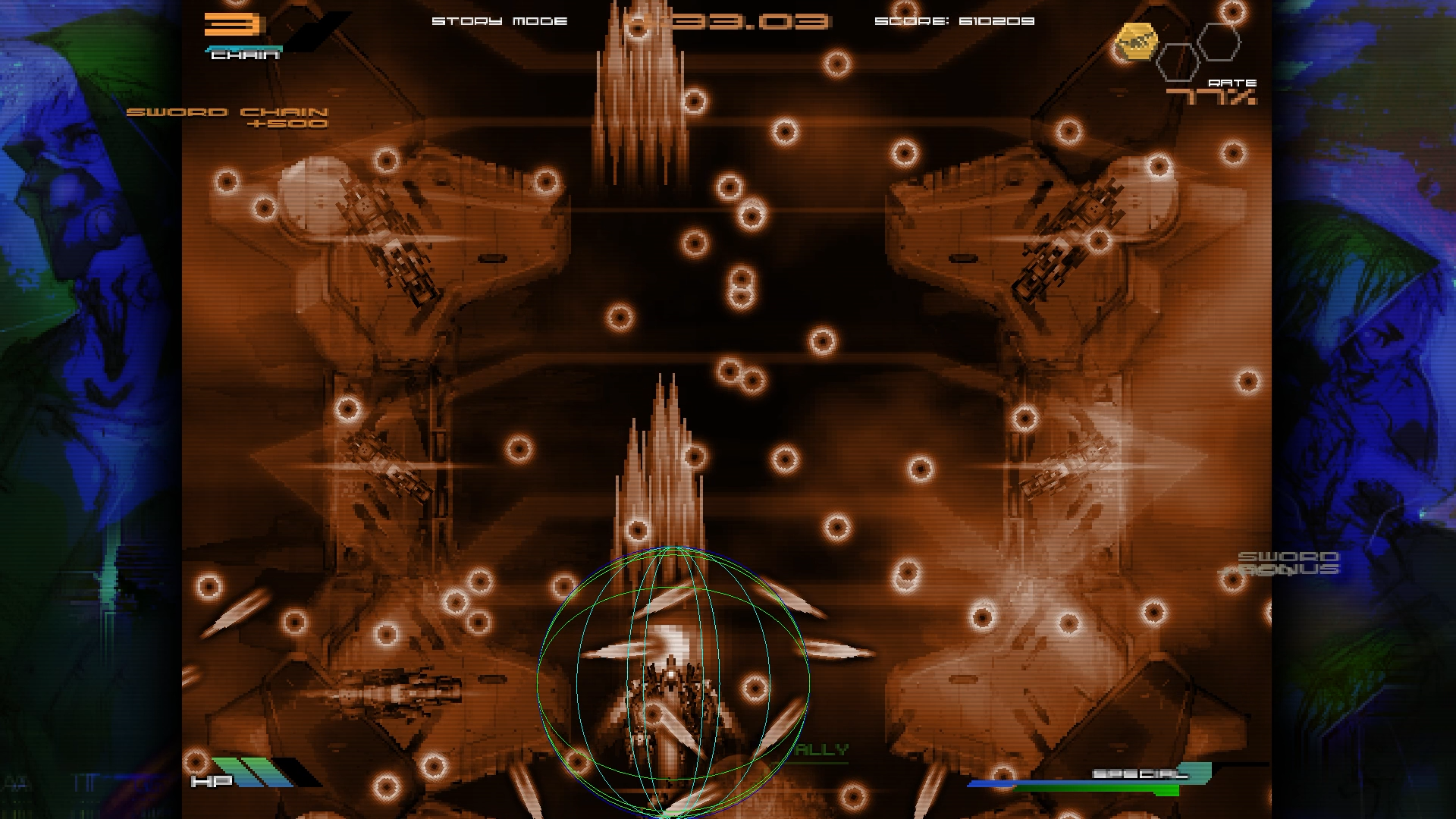

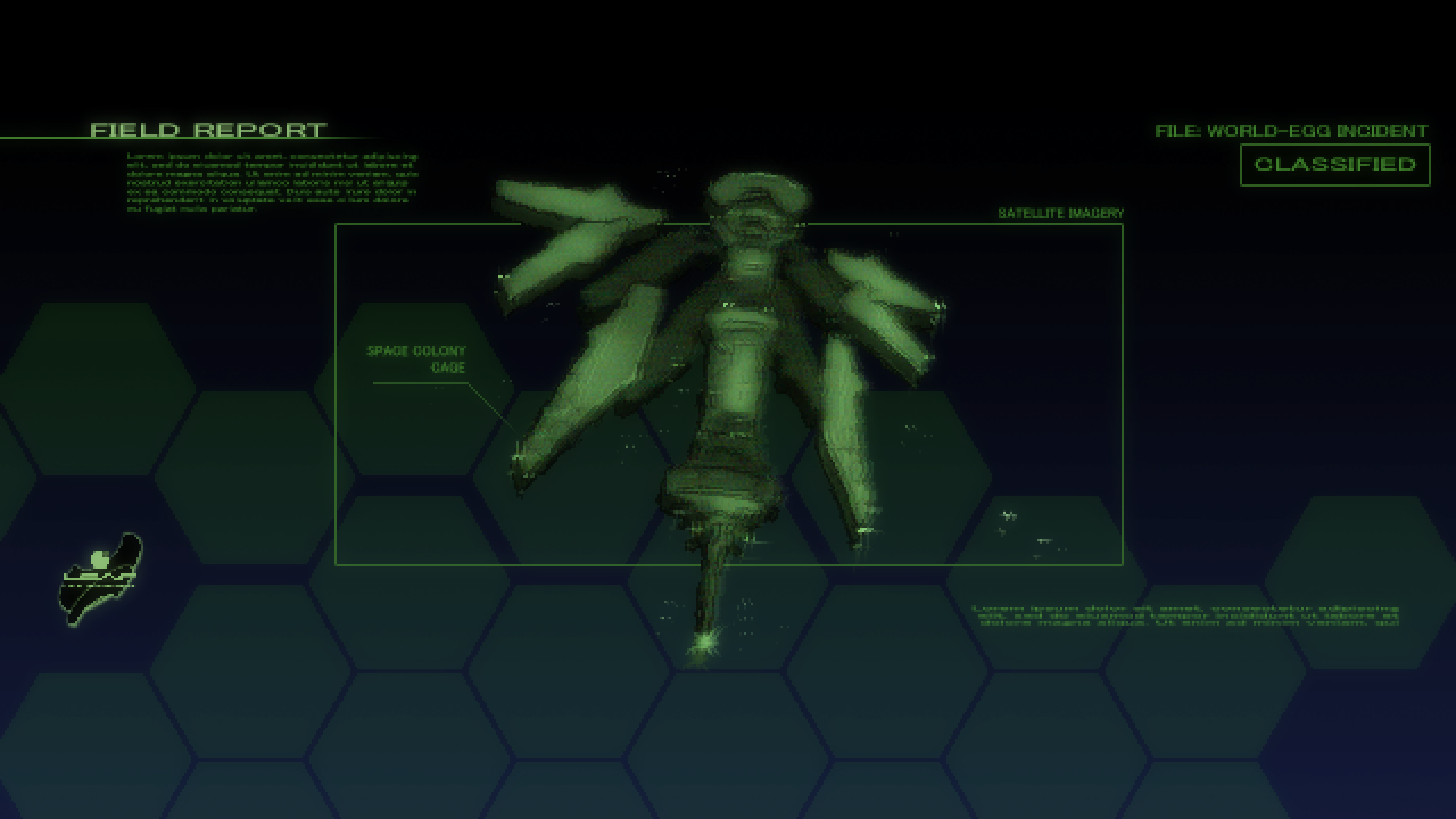

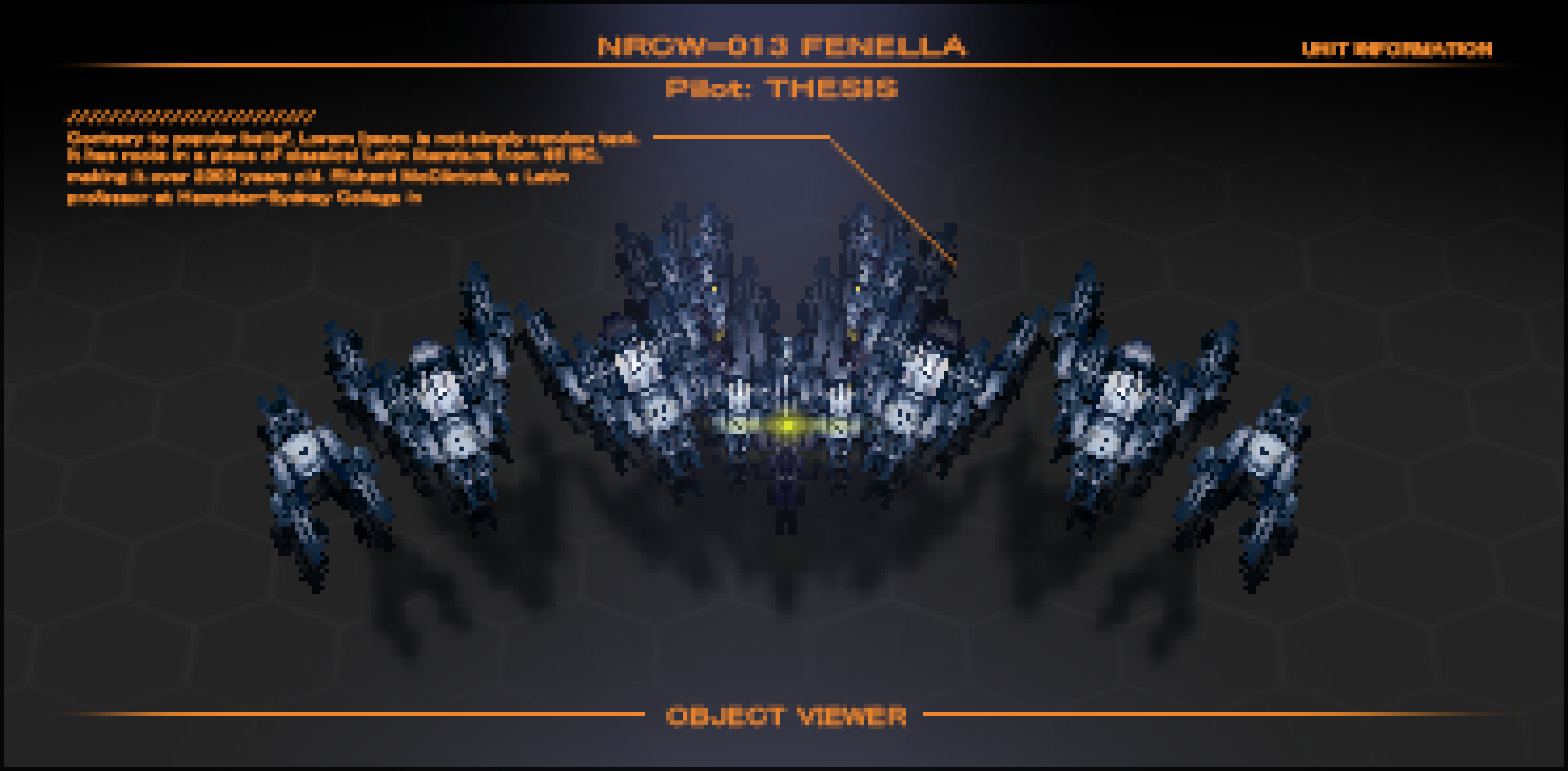

One look at Birdcage and you might mistake it for an arcade shoot 'em up (or shmup, as it's also known for short) from the late '90s, in particular Treasure's Radiant Silvergun. If you're keen, check out the Evercade consoles for a lineup of classic shooters of the era, from SNK and Toaplan.

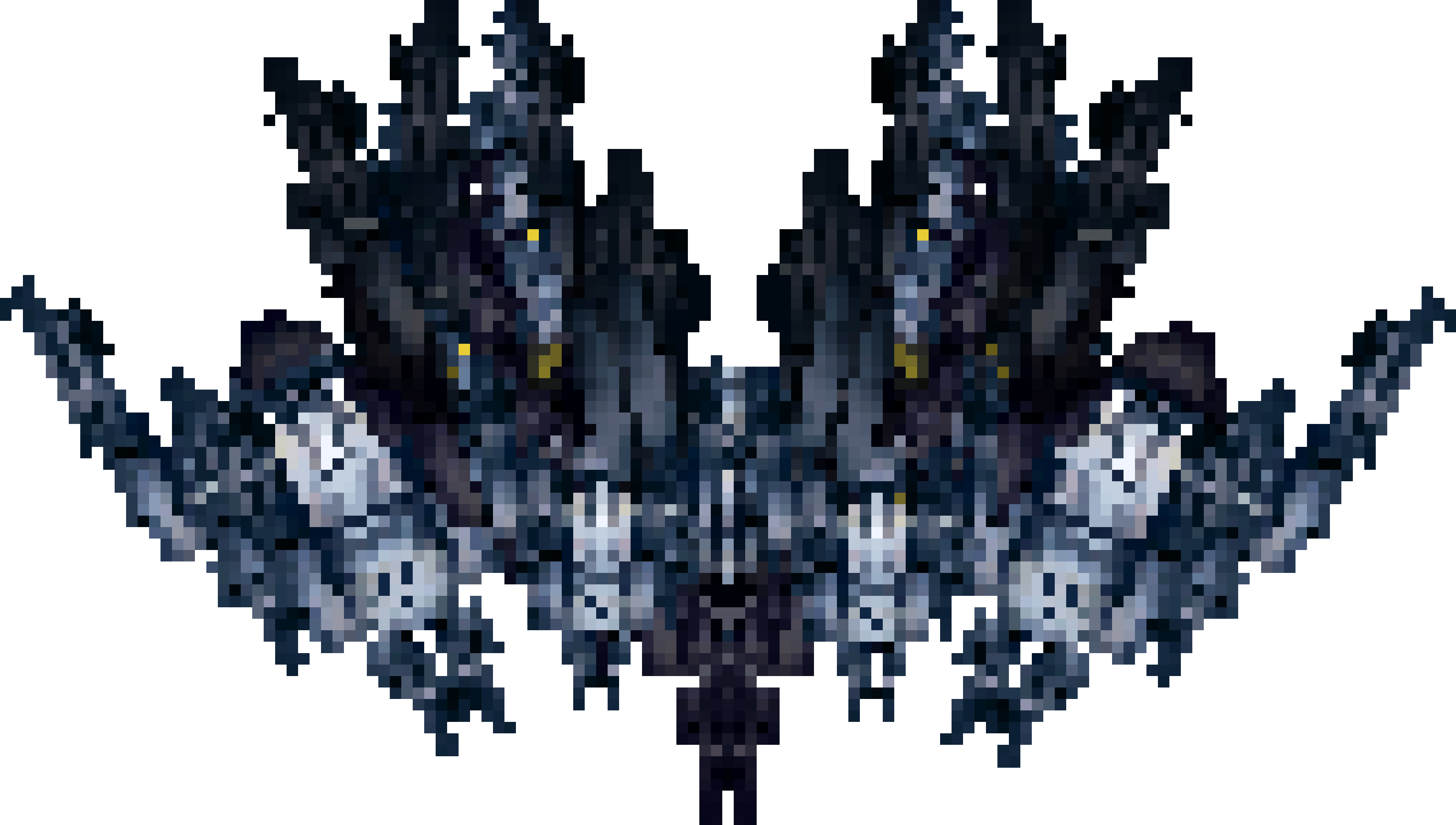

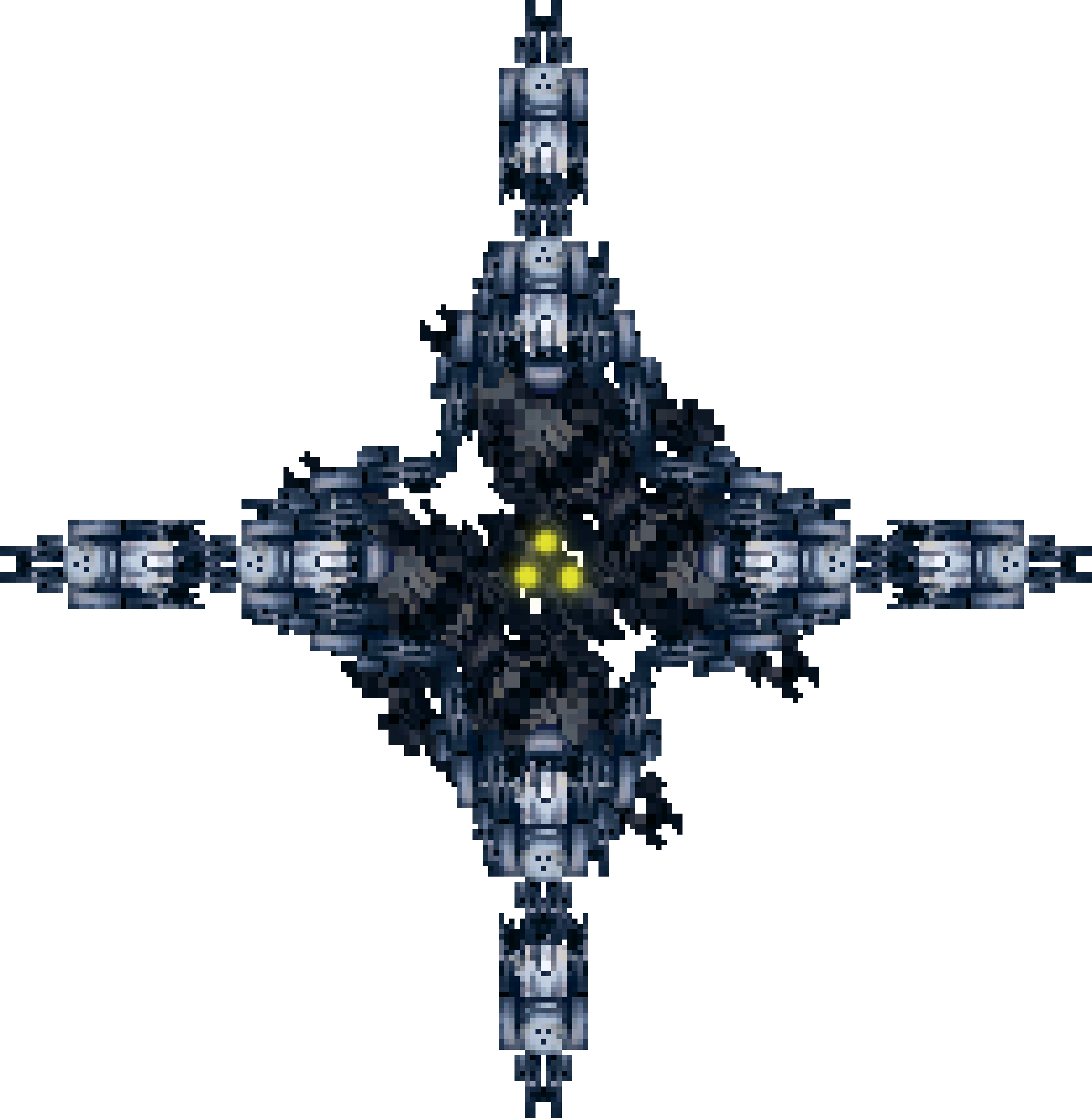

It's an aesthetic that indie developer Polygon Bird wholly commits to with sprites that show the individual pixels rather than the smoothed-out botch jobs in modern re-releases. Even the menu fonts have a deliberate fuzziness rather than looking too clean in HD. It is, as co-director Barry Topping puts it, "where the flavour is."

"It's not necessarily like applying restrictions, but between the idea of clean and dirty, we really tried to lean more towards dirty because that feels more in keeping with the time," he tells me. "There are a lot of video elements in Birdcage, and they are all standard definition, and then they are scaled up to whatever your display size is."

Birdcage has actually been in development as early as 2022 by co-director Giannis Milonogiannis, who had been working on it by himself. "I had met Barry on Twitter, and we were always talking about how we needed to make something together," he says. "Initially, he was going to be just doing music for the game, but then we hit it off so well. We got along creatively, so we decided to do it together, and we just shared everything creatively."

The pros of GameMaker

For both, Birdcage is their first commercial release as game developers, Milogiannis is a comic book artist, with credits including Batman, Ghost in the Shell, and Cyberpunk 2077, while Topping is a musician better known by his performing name Epoch. But the latter's involvement in composing game music, including Paradise Killer and Thatcher's Techbase, helped pave the way for him.

"Generally, audio people can be further down the pipeline in terms of priority, but I've always championed that music can sell copies of a game," Topping explains. "So even in projects where I was only really there to make music, I was still as present as possible. Through osmosis, I was just trying to pick up as much good practice and watch out for mistakes."

While both are new to coding, Birdcage has been developed using GameMaker rather than more prominent game development software like Unreal or Unity, which have sophisticated visual scripting tools that make development more accessible to those without a coding background.

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

"I started learning GameMaker for real in 2017, and they do have visual coding, but that just ended up being more confusing to me, so I learned their language because it just seemed more straightforward," Milonogiannis explains, who essentially worked with a manual opened up on his devices at all times. "I had no prior knowledge of coding, but it took me from 2017 to 2022 to be confident enough to say that maybe we can make a full game."

"GameMaker's a pretty good engine because it supports all platforms and it's quite a low bar to get into," Topping adds. "I found I'll never find any coding properly intuitive, but once you get to grips with the basics of GML (GameMaker Language), I think it all makes sense."

2D is king

That GameMaker is also a primarily 2D game engine helped impose a limit on any vision getting out of hand. It's perhaps ironic then that, at a glance, Birdcage does appear to contain a mixture of 2D and 3D graphics, just like in Radiant Silvergun's visuals. It also arguably hails back to the 32-bit era and even earlier, when 3D texture-mapping was done with sprites.

The most impressive-looking shmups have always made good use of parallax scrolling to create the illusion of depth, Topping citing Thunder Force IV on the Mega Drive as a constant reference. But Milonogiannis also worked hard to emulate 3D with two other classic methods, sprite-scaling and digitised sprites.

"I don't have any experience in 3D engines, but we made some models in Blender and took pictures of those essentially and turned them into sprites," he explains. "Then those models we'd cut up into different ship and enemy sprites. So, a lot of the stuff in the game is made from a template of models that we could cut up and paint over."

One other nice touch, which harkens back to the technical constraints of older shmups, is when a certain number of bullets fill the screen, the game will also deliberately slow down by a few frames. Modern hardware is more than capable of handling the sprites and bullets thrown on the screen these days, but it's just as much a creative choice to mimic that effect, and also design it so that you have a bit more time to react and survive against the bullet hell.

"We didn't have a guideline or design bible with constraints as far as the number of colours go or the sprites on screen or the bullets or anything like that – it's just the two of us, so as soon as we do something that doesn't fit the game, you can tell instantly," Milnogiannis explains.

"We were pretty casual shmup players when we started this, and over the course of the past three years, it kind of became a study of what a shmup is and what makes it fun. So going back and playing some of these games, then trying to figure out why they were designed a certain way, has helped us balance the game overall."

Birdcage releases for PC on 18 November, and you can try a free demo on Steam.

Alan Wen is a freelance journalist writing about video games in the form of features, interview, previews, reviews and op-eds. Work has appeared in print including Edge, Official Playstation Magazine, GamesMaster, Games TM, Wireframe, Stuff, and online including Kotaku UK, TechRadar, FANDOM, Rock Paper Shotgun, Digital Spy, The Guardian, and The Telegraph.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.