How Resident Evil Requiem is designed to make horror feel personal

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Content warning: this article discusses graphic violence, disturbing imagery, and mature themes in an 18+ game.

Resident Evil Requiem asks you to slow down and look. After spending time with an early demo, what stays with me isn’t just the combat or the dual-protagonist setup, but how assured the game feels in its visual decisions, and how deliberately those choices frame mood, character, and space. It's in how a corridor holds my eye for a second too long. How motion, or the suggestion of movement, feels loaded.

With Requiem, Capcom isn’t using the RE Engine to flex and show off, but to control how it feels to move through a room, or in this case, the fading elegance of Rhodes Hill Chronic Care Center. It also brings together two strands of game design, the third-person of Resident Evil 4, with the first-person of newer Resident Evil Village; it's something of a celebration of the series' highs.

The demo opens with Leon S. Kennedy arriving at the decaying sanitarium in a photoreal Porsche Cayenne Turbo GT, designed just for the game (okay, this is a graphical flex). Outside, rain slicks cracked stonework, mist blurs hard edges, and the building’s silhouette hangs in the distance, refusing to reveal its true shape. It’s striking immediately, but what stood out to me was how restrained it all felt.

Inside, polished wooden floors reflect low, humming lights, creating stretched, uneasy reflections. Corridors are wide, but never generous. Sightlines run just long enough to remind you how exposed you are. It’s classic Resident Evil spatial thinking, but with modern nuance. This is a space that rewards stopping, looking, and second-guessing yourself rather than pushing forward on instinct.

The RE Engine’s material work does a lot of heavy lifting here. Wood looks worn but maintained. Stone feels cold and institutional. Metal fixtures catch the light in ways that keep pulling my gaze ahead. Long before anything attacks, the environment is already telling its own story, and it's one that instinctively makes me feel uneasy.

Zombie killing like its 2005

That calm doesn’t last. A nurse escorts Leon into a room lined with bodies hooked up to ventilators and UV wiring. The composition is almost clinical, symmetrical, and sterile. When a zombie tears her apart and those ‘lifeless bodies’ begin ripping free from their tubes, the visual order collapses instantly.

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Combat still follows familiar Resident Evil rhythms – dodging, rolling, stomping, snapping off headshots – but it’s been visually rethought. Leon carries more weight now. His age shows in the timing of his animations, in how long it takes him to recover. Enemies don’t just advance; they collide, stumble, and bumble into one another in ways that feel unplanned and realistically random.

One moment captures this perfectly. I shoot a chainsaw out of a zombie’s hands. Instead of sparking and breaking, it falls, spins, and skids across the floor, becoming a hazard in its own right. Another zombie grabs it, accidentally impales a companion, then lurches toward Leon in a grotesque parody of an embrace, resulting in a buzz cut through our hero’s chest. It’s horrifying, but also oddly playful, the kind of chaos that comes from physics and animation pushing against each other rather than following a script.

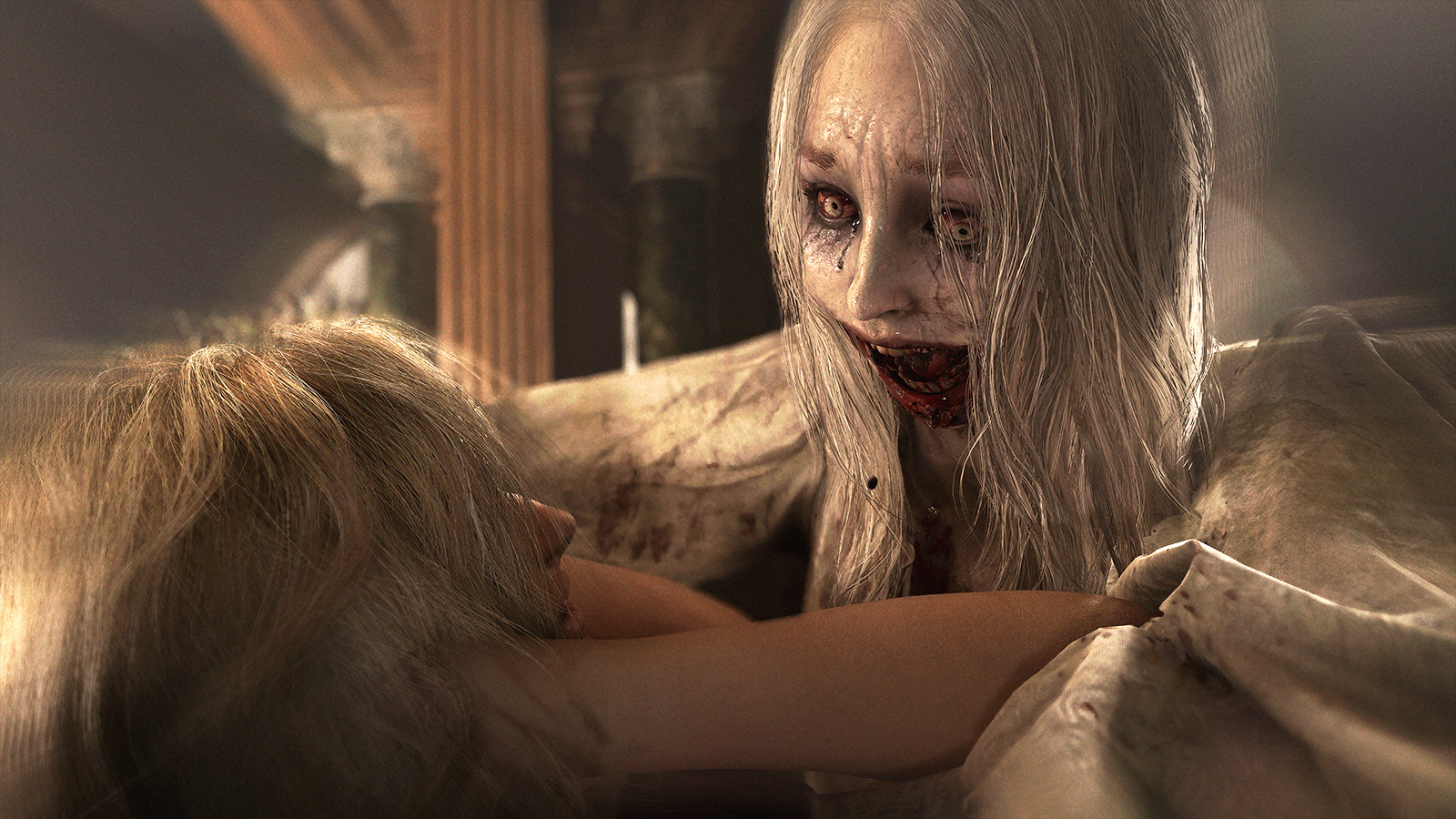

Up close, the character art is exceptional. Zombies have tears in their eyes. Jaws slacken and quiver as they moan. Their movements feel hesitant, clumsy, and almost embarrassed. They bump into furniture and each other in ways that feel messy and human. This goes beyond technical fidelity. It feels observed, like someone spent time watching how bodies sag, hesitate, and lose balance before animating them.

Changine perspectives

What stands out most is how clearly Requiem separates its protagonists simply by where the camera sits. Leon’s sections are third-person, framed for awareness and flow, a callback to Resident Evil 4. Grace Ashcroft’s is a first-person, modern Resident Evil, and the difference isn’t superficial; it changes how the world must be understood and experienced.

As Grace, the game becomes intimate to the point of discomfort. You’re no longer watching horror play out; you’re pressed right up against it. The camera forces you to read textures, shadows, and movement at literal arm’s length, and suddenly the RE Engine’s lighting work becomes critical rather than decorative.

Her section leans heavily into classic Resident Evil puzzle design. To escape the sanitarium, I need to find three ornate objects hidden throughout the building. That search pulls me through a series of carefully composed spaces: candle-lit rooms with soft flicker and deep shadow, blood-smeared kitchens where light pools uneasily on steel counters, and medical examination rooms washed in a sickly institutional glow.

Here, lighting isn’t just setting the mood. It’s functional. Some zombies slow or recoil under bright light. Others fixate on fragments of their former lives. One mutters “experimentsssss” while tapping at a computer terminal. Another repeats a mundane task. These behaviours are read visually before the choice between fight or flight ever kicks in, forcing you to pause and interpret a room rather than react on instinct.

Creature design as threat

Playing as Grace is about restraint. One zombie is manageable. Two is dangerous. Three is a mistake. That tension is reinforced by character design that communicates risk instantly. In one room – a lavish bar space with a glossy grand piano and scattered candles – several zombies linger. One, dressed in a flowing evening gown, sweeps the room singing and howling. I laugh, quietly say “nope,” and back away. There’s no prompt, no scripted scare. The scene reads clearly on its own.

Requiem’s enemies don’t feel like simple obstacles. Each one reads as a deliberate visual setup, where costume, silhouette, animation, and sound work together to signal danger long before mechanics take over. That banshee-like zombie, for example, is a ring-leader of sorts; if she sees you, the others attack, and the wail is a one-hit that can knock Grace off her feet.

That approach peaks with a recurring monstrosity that stalks Grace: a colossal, blimp-like naked zombie that tears through walls and reshapes the environment as it moves. It’s grotesque, but also strangely compelling in motion. Its bulk absorbs light, throws shifting shadows, and turns corridors into moving compositions of flesh and darkness. It stops feeling like a boss fight and starts behaving like part of the building itself, something that blocks routes, reshapes rooms, and refuses to be ignored.

Shaking off the shackles

When the demo shifts back to Leon, the tonal change is immediate. The same creature that terrorised Grace becomes something to confront head-on. Shotgun blasts inflate its body before it bursts in a spray of blood and viscera, collapsing into a heap of loose skin. The moment isn’t just cathartic; it also visually reinforces Leon’s authority.

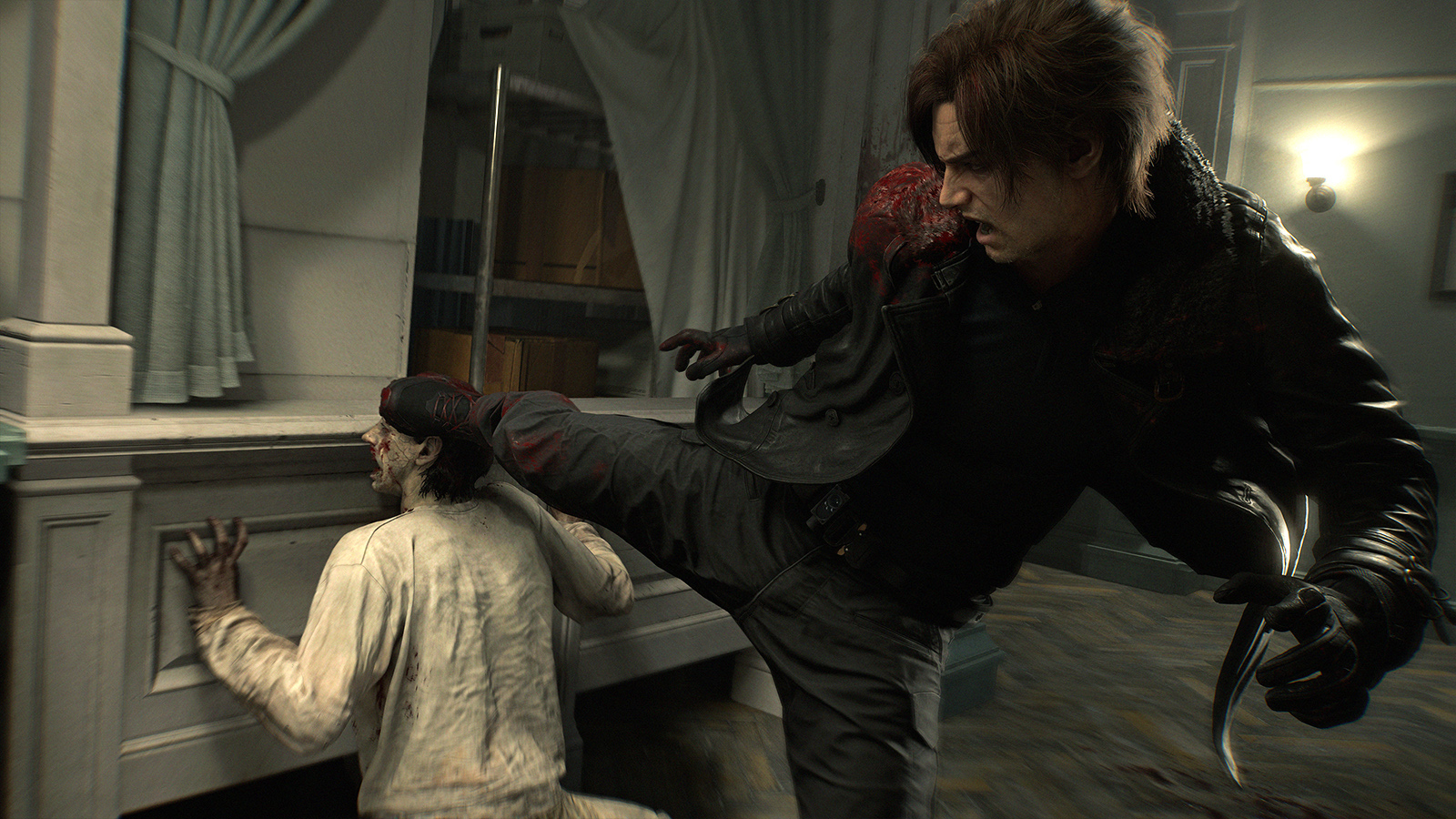

Returning to earlier spaces, Leon reveals new routes as he can force open doors that Grace was too weak to access. But it's the confident new way to play that feels like a shift in tone. Leon’s combat animations are assertive and clean: throwing an axe into a zombie’s skull, roundhouse-kicking another, wrenching the axe free, and burying it in a third. The choreography is violent, but easy to read, designed for clarity as much as excess.

Built on the RE Engine, Resident Evil Requiem feels like the work of a studio that knows exactly what its tools are for, and how to balance the needs of the best horror gaming with pure spectacle. Advanced lighting, physically based materials, detailed animation, and careful optimisation are all present, but they’re never showy. They exist to support framing, mood, and emotional response.

What impressed me most was how personal the horror feels. Perspective and art direction do much of the work, with the technology quietly backing it up. Vulnerability and confidence become opposing experiences you feel immediately when control switches hands. This remains just a slice of the full game, but I can’t wait to explore more of Requiem’s uneasy beauty.

Ian Dean is Editor, Digital Arts & 3D at Creative Bloq, and the former editor of many leading magazines. These titles included ImagineFX, 3D World and video game titles Play and Official PlayStation Magazine. Ian launched Xbox magazine X360 and edited PlayStation World. For Creative Bloq, Ian combines his experiences to bring the latest news on digital art, VFX and video games and tech, and in his spare time he doodles in Procreate, ArtRage, and Rebelle while finding time to play Xbox and PS5.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.