MIO: Memories in Orbit’s stunning hand-drawn art direction explained by its creators

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Five times a week

CreativeBloq

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Once a week

By Design

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Once a week

State of the Art

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Seasonal (around events)

Brand Impact Awards

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

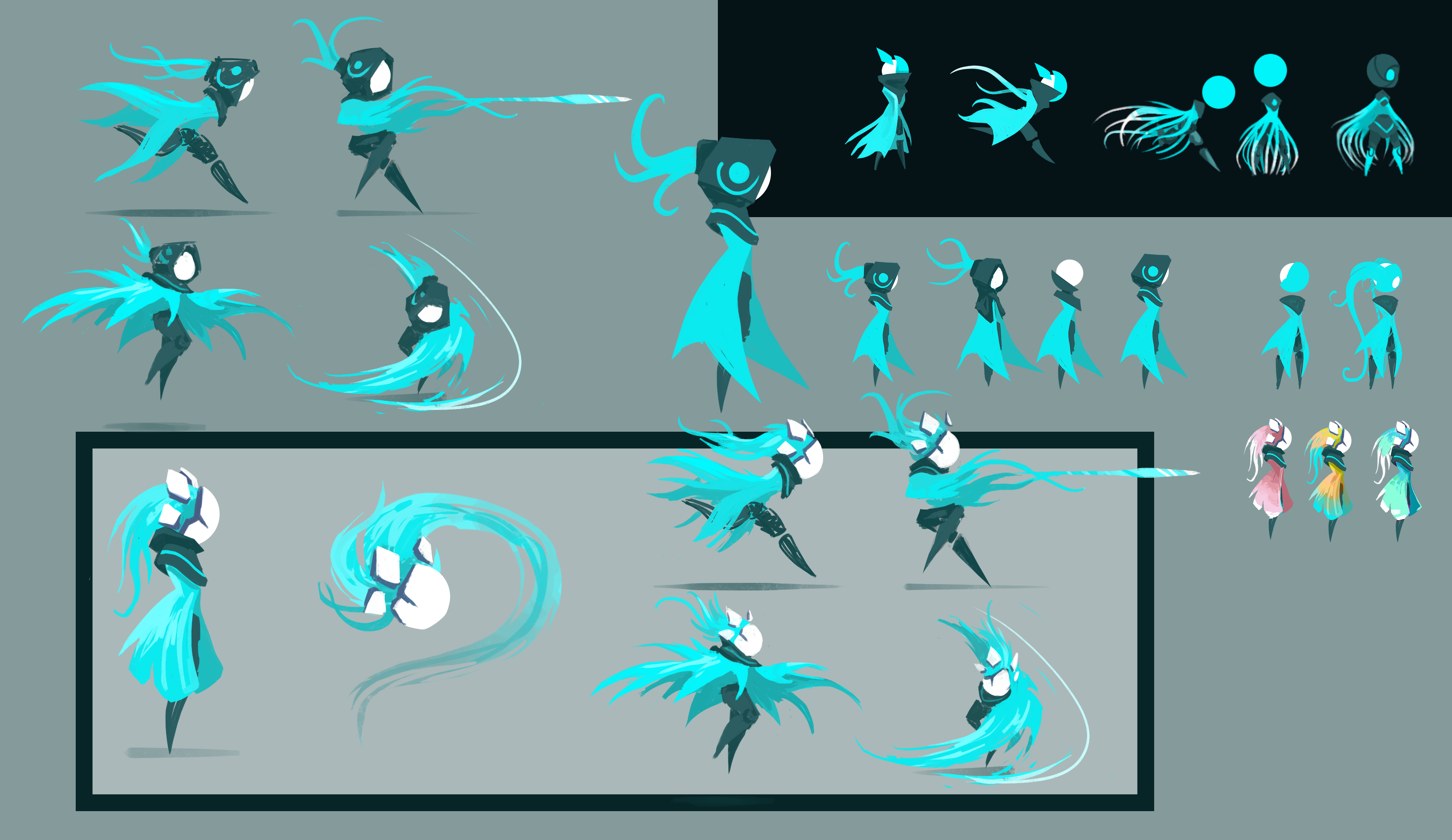

From the moment my sleep little robot awoke aboard the Vessel in MIO: Memories in Orbit, it’s clear this is not in a conventional 3D game. I've been exploring the game's maze of puzzle rooms, lore, and bosses for some time ahead of release, but it's the art style that has been prompting the dev team to request more.

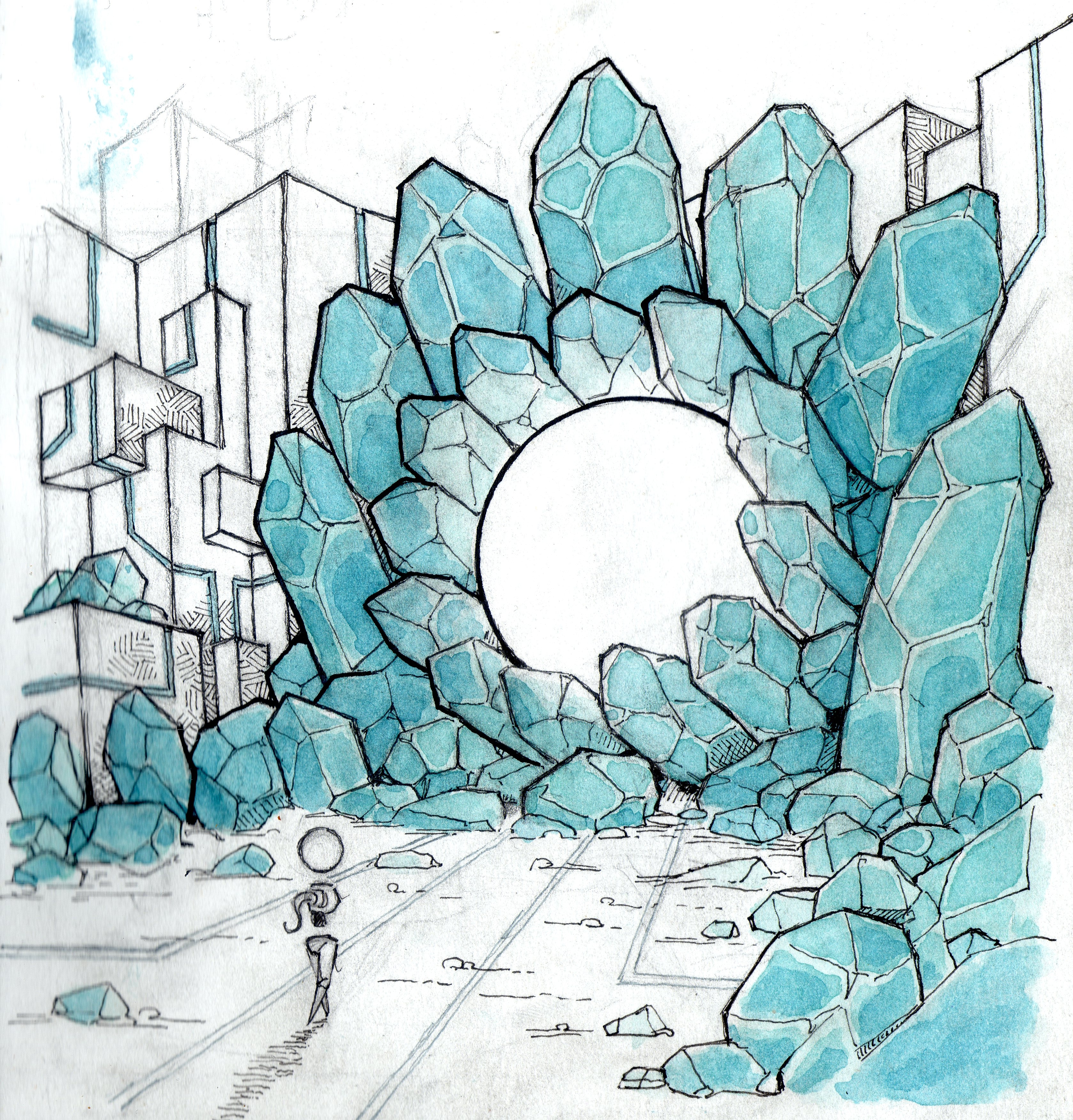

Douze Dixièmes’ new Metroidvania blends comic line work, painterly colour, and 3D space to create an otherworldly environment that feels hand-illustrated rather than rendered, one that moves like an animated bande dessinée. (Read our list of inspirational indie game devs for more.)

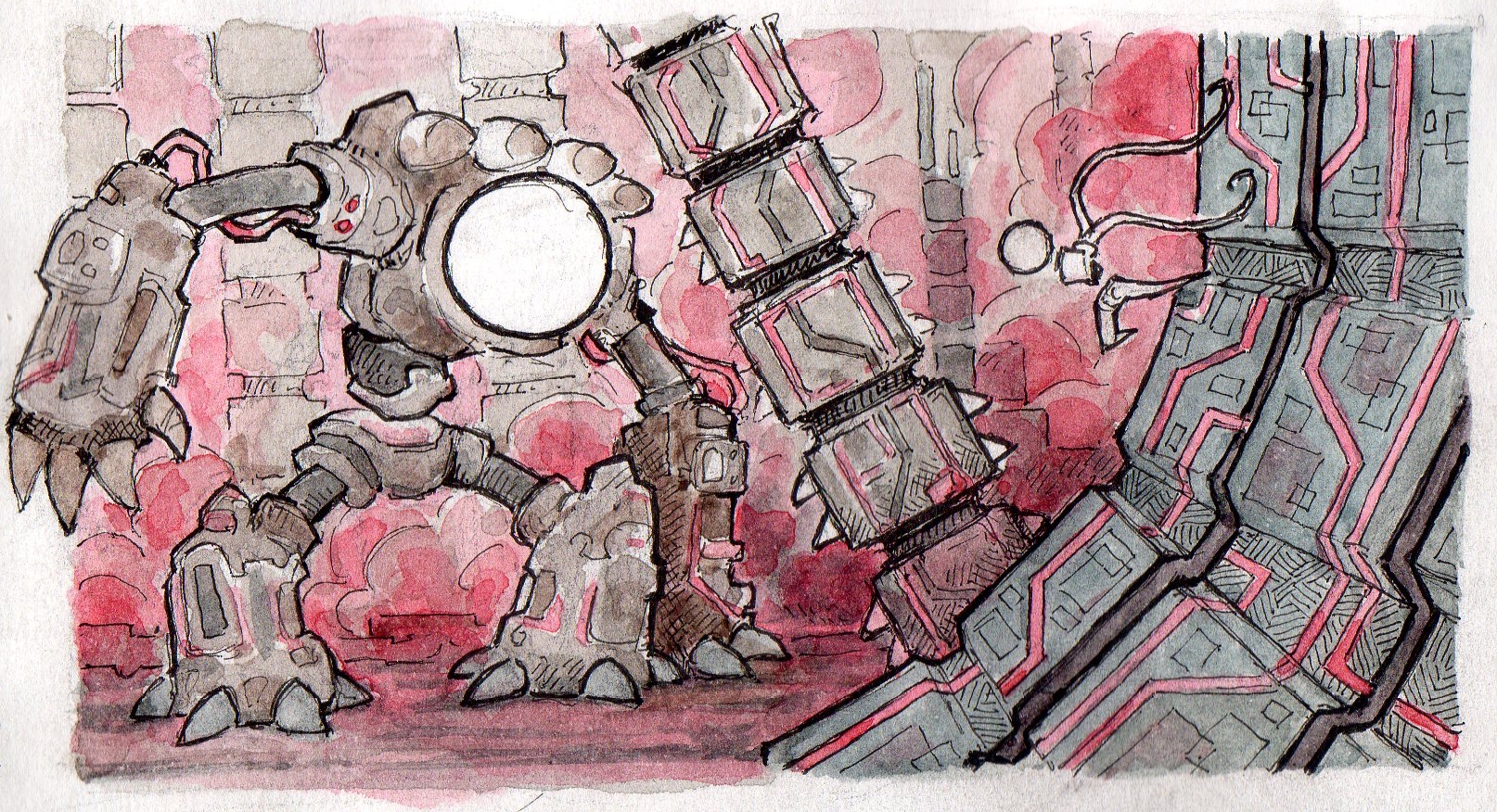

“We already started working on this type of rendering for our first game, Shady Part of Me. The art direction is a strong collaboration between the art director, Etienne, and the render dev, Joran. They were working on a proprietary engine that was specifically developed for the game, mostly by Joran and the creative director of the project. MIO is the result of quite a small team's work and the art of the game all the more,” says Sarah Hourcade, co-founder and executive producer.

She notes that the tools themselves helped enforce the style: “The tools available to the artists - proprietary engine and Blender – did not allow to drift a lot, since all the textures, outlines and rendering is procedurally made by the engine. The final art direction is the result of Etienne and Joran talking a lot during five years and adjusting sliders in the engine.”

Building a watercolour world

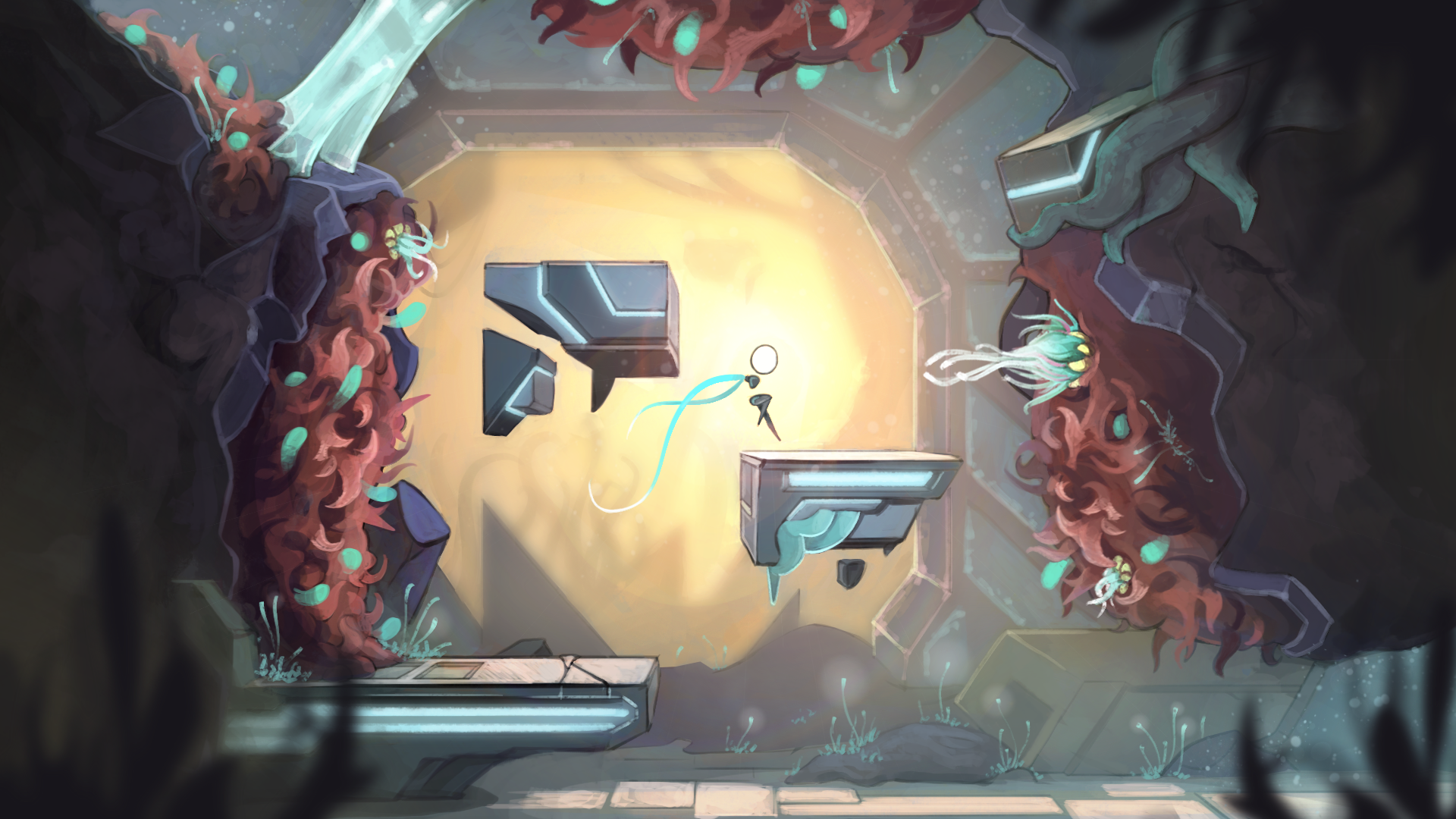

The Vessel itself, a sprawling, decayed ark overgrown with vegetation, broken machinery, and rogue robots, is designed to feel alive yet melancholic, a world of memory and forgotten history that demands to be uncovered and explored. Etienne Thibault-Buisson, art director, explains how colour and composition bring this world and its motifs to life.

“We used several tools and strategies to achieve this. The use of limited palettes, often a primary colour and one or two secondary colours, prevents visual information overload. Similarly, the deeper the elements are, the more monochromatic and uniform they tend to be. The use of pastel tones lends a more serene and antique feel to the overall scene. The depiction of vastness is achieved through frequent contrasts between cramped and expansive areas, and occasionally by zooming out of the camera to reinforce the sense that the setting overwhelms Mio."

Thibault-Buisson adds, "In the end, these were general rules that were meant to be bent in order to create some unique moments through contrast with the rest of the world. The process was very organic, and most of the scenes were checked by one person in the studio, our art director, in order to feel if the mood was on point and adjust if necessary.”

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Gameplay aids art direction

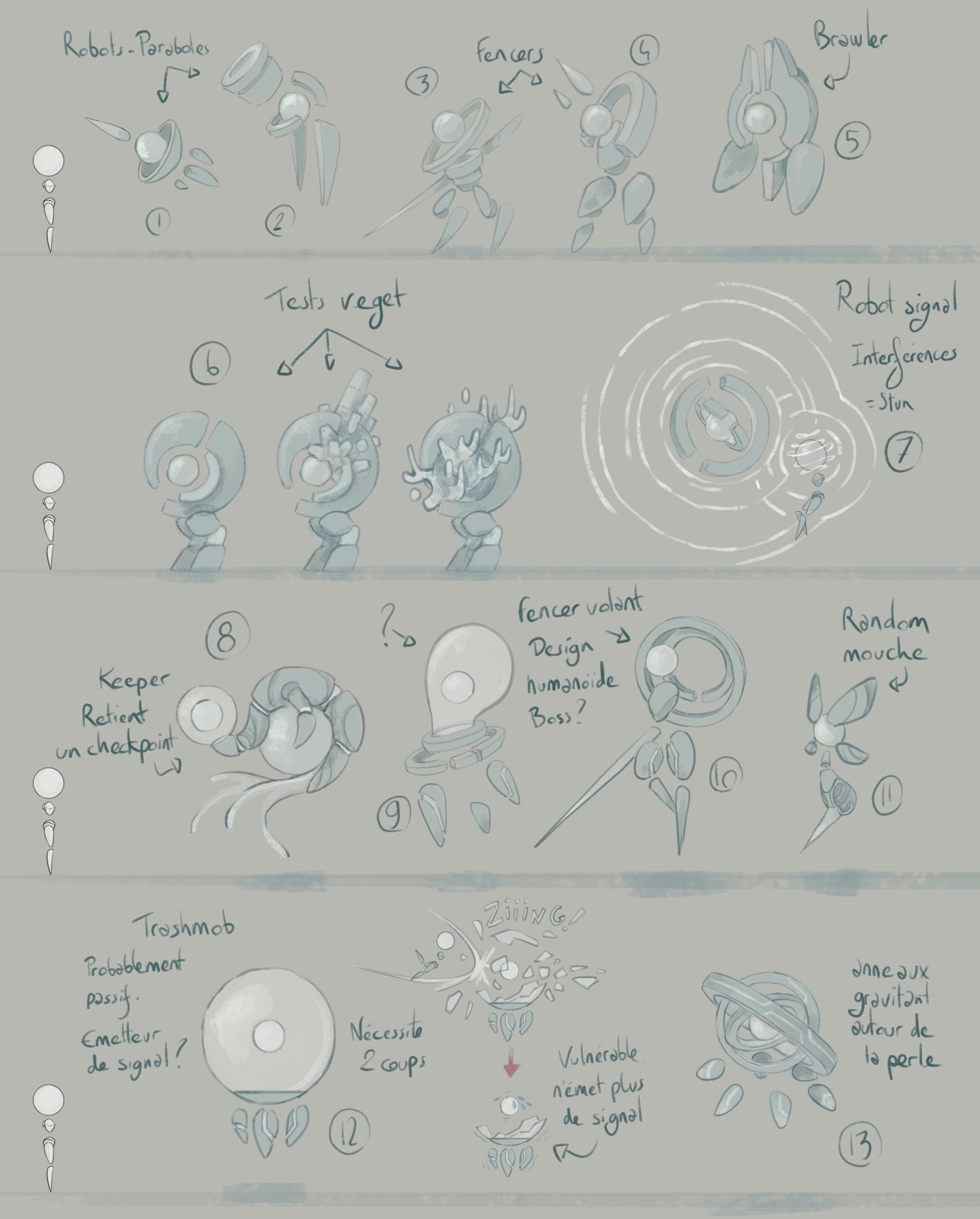

Creating this illustrated feel wasn’t just aesthetic; it also guided gameplay. In a Metroidvania, visual clarity is non-negotiable as you need to understand a level's design on an instinctive level to encourage exploration, and enemies need to easily signal attacks and patterns.

Hourcade describes the approach: “A lot of small rules were established: no asset with too many edges because it would create too many outlines, direction and orientation of edges, […] the most important one was that we decided to differentiate the rules depending on the moment of the game: if it’s a strong action / platformer moment then the art must be at the service of the gameplay."

This approach and these rules are the kind of thing all devs can learn from: "Not too many assets, nothing on the foreground, simple geometry, clear limit between playable ground and background, and the art will focus on the far away background. But a metroidvania is also made of more peaceful moments to create a good rhythm of challenge, and in these scenes, artists were given full liberty to set the mood,” continues Hourcade.

The hybrid approach of painterly textures layered over 3D spaces posed challenges for the team. The engine was built and designed through experimentation with visual design and assets, and the team often found that the art direction pushed the limits of what the engine and pipeline could handle.

One standout scene, near the story’s end, pushed the engine to its limits. Hourcade and director Oscar Blumberg recall: “At the beginning of production, we built the engine while experimenting on the visuals and assets we wanted. During those times, it happened all the time. One of the best examples of a scene that pushed the limits of the engine is a very end-of-the-story moment where you find this very big character, and you walk on vines around her in deep space. It’s a fully atmospheric scene where the staging was essential. The engine is built to render flat gameplay and was never made to support a spherical plan, so instead of changing the engine to fit the art direction, it is the entire stage that rotates around the character just for this scene.”

Breaking with realism

Lighting, too, serves narrative rather than realism. “One of the advantages of choosing a stylised rendering is the ability to easily break free from the constraints of realism in service of the intended message or even readability. Just as in 2D, lighting is sometimes directly managed by colour rather than by a realistic lighting system. Sometimes, 2D images are even integrated into the scene. The workflow is similar to that of an illustration,” Etienne explains.

Level design mirrors the narrative’s fragmented memory theme. “Since the environment might be explored in a non-linear way, I wouldn’t say it was conceived in a ‘sequential’ way like a graphic novel. Instead, it’s more like a collection of interesting places that the player might stumble upon in any order. To achieve that, when designing new places, we use a mix of two approaches: 1) What is the purpose of this place? and 2) is there some lore that we haven’t conveyed yet?” says Sévan Kazandjian, game designer.

A pivotal art-direction decision came three years into development: reworking all material systems to focus on painterly shading with strict colour control. Hourcade and Blumberg explain:

“The single art-direction decision that had the most significant ripple effect on production was changing all the material systems around year three of development. We used to have a [pipeline] where artists had to deal with lighting and realistic renderings, to which we then applied the drawing effects in post-processing, and it was very difficult to maintain. The colour palette was pretty hard to keep persistent. That’s when we decided to deal with the shadings like Photoshop does with very defined colour palette sets, mostly one global light and a very strict control of the colours in each biome in order to gain a more painterly aspect in the game. It also allowed us to go further in the objective of breaking free a little from traditional sci-fi art and embrace our poetic and eerie art direction without complexes.”

Their advice to other indie teams? “Don't hesitate to completely disregard your engine's normal systems. As long as you achieve what you want, it's not a big deal" says Hourcade. "Don't be afraid to change everything. We were very scared at the beginning of the change, but it was done in two months and everything was just simply better,” adds Blumberg.

Explore the Vessel and its memories when MIO: Memories in Orbit releases 20 January on Xbox Series X/S, PS5, Switch, and PC.

Ian Dean is Editor, Digital Arts & 3D at Creative Bloq, and the former editor of many leading magazines. These titles included ImagineFX, 3D World and video game titles Play and Official PlayStation Magazine. Ian launched Xbox magazine X360 and edited PlayStation World. For Creative Bloq, Ian combines his experiences to bring the latest news on digital art, VFX and video games and tech, and in his spare time he doodles in Procreate, ArtRage, and Rebelle while finding time to play Xbox and PS5.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.