How art lays the foundations for indie games

Five artists explain how their work influenced game worlds, stories and emotions.

Drawings and paintings take on a whole new dimension when they’re used to create a game world. As emotive as animated films and TV shows can be, there’s nothing as special and engrossing as being immersed in a setting where you can dwell on and influence a moment rather than watching it pass by.

Sometimes the atmosphere, emotion and mystery of just one piece of artwork is enough to inspire an entire game concept (also see our What is concept art? explainer).

Japanese styled RPG Eastward was conceived when artist Hong Moran sketched a “weird monster dormitory building” that resembled the once infamous Kowloon Walled City of Hong Kong, an overpopulated, anarchic and hellish-sounding enclave that was demolished in 1994.

“We got excited about the design and came up with a game that would fit around the aesthetic,” says Hong. “Eastward unfolds within a cruel and unforgiving world, where every individual is forced to confront the pressing issue of survival. The storyline delves into the depths of our human existence, exploring the characters’ hidden secrets and their burdened pasts.

The highs and lows of the story take the characters into moments of joy, sorrow and shades in between, but instead of guiding players on an emotional journey, Hong prefers to let them find their own way. “I feel that rather than leading players, it’s more about sharing the experience with them,” he says.

He focuses in particular on colour and fine details in his artwork as a way to help the player experience the characters’ emotions. “We’ve put a lot of effort into the details because they make the story more believable and our characters’ emotions more nuanced,” Hong adds. “This makes it easier for players to immerse themselves in the story.”

Planet of Lana, a platformer and puzzler combo created by Wishfully Studios, is another game underpinned by one piece of art that encapsulates the mood of the story and the relationship it’s centred around.

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

“The game originates from a single image I drew back in 2017 and that we still use as the main key art,” says creative director Adam Stjärnljus. “I had an idea of this side-scrolling sci-fi puzzle adventure with a young girl and her creature companion, and drew an image to represent the idea.”

The artwork he created attracted collaborators and kick-started the game’s production. “The reaction I got when showing the image to people pushed me forward and made me realise that the game could be something special,” Adam recalls.

“Over the course of the next year, I had a lot of extremely talented people join the project, and then in 2019 we collectively started Wishfully Studios with the goal of releasing our first game, Planet of Lana.”

Adam was influenced by games from the 80s and 90s that he grew up with: classics such as Oddworld, Another World and Prince of Persia, as well as more recent cinematic platformers like Limbo and Inside, and the film Spirited Away.

He adds: “The art style was heavily inspired by Studio Ghibli and I tried to find a unique expression in the contrasts of a painterly environment, and with characters and creatures that have a simple flat-shaded look, combined with the black foreground that makes you feel as though you’re kind of looking into a theatre stage.”

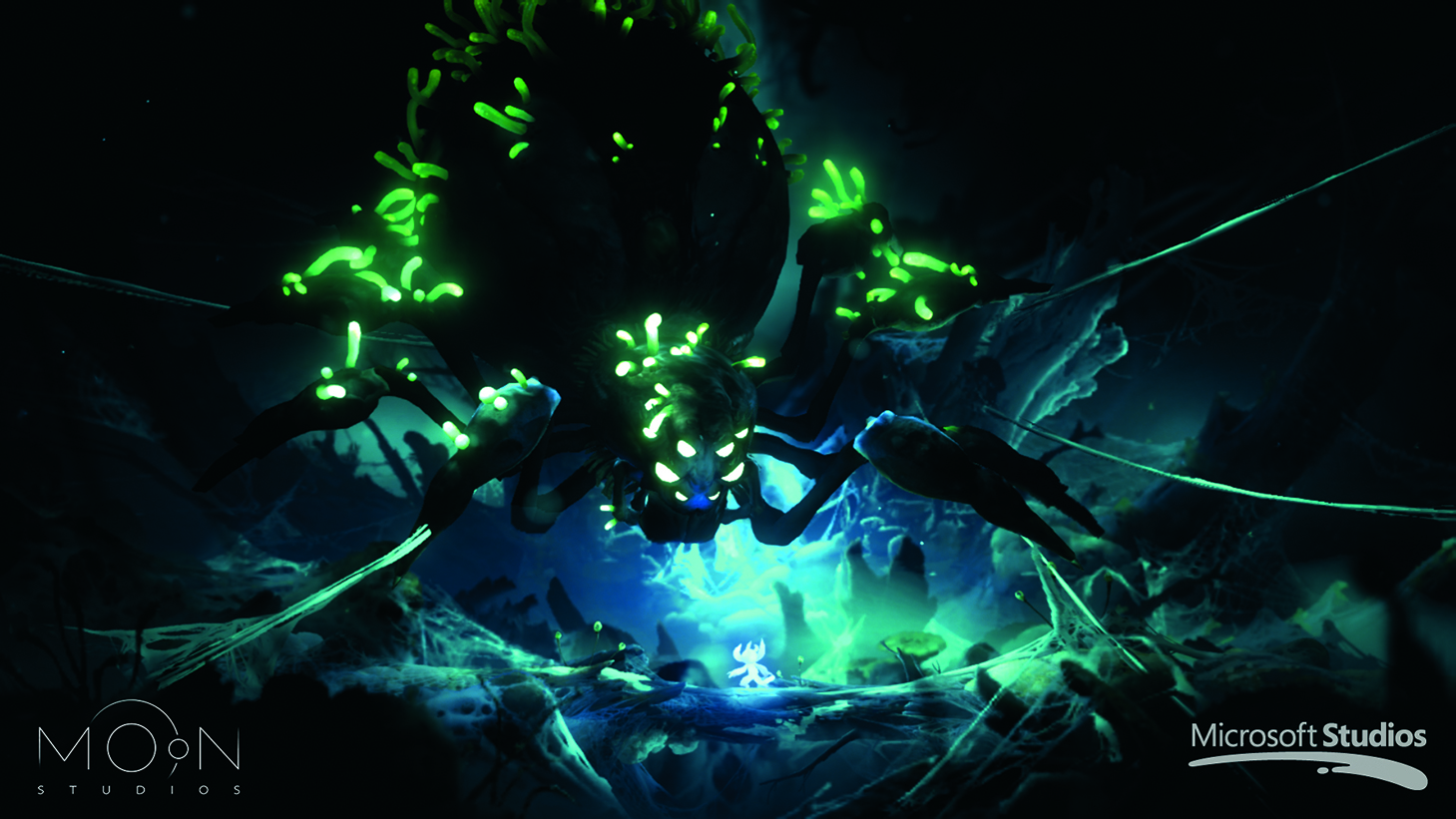

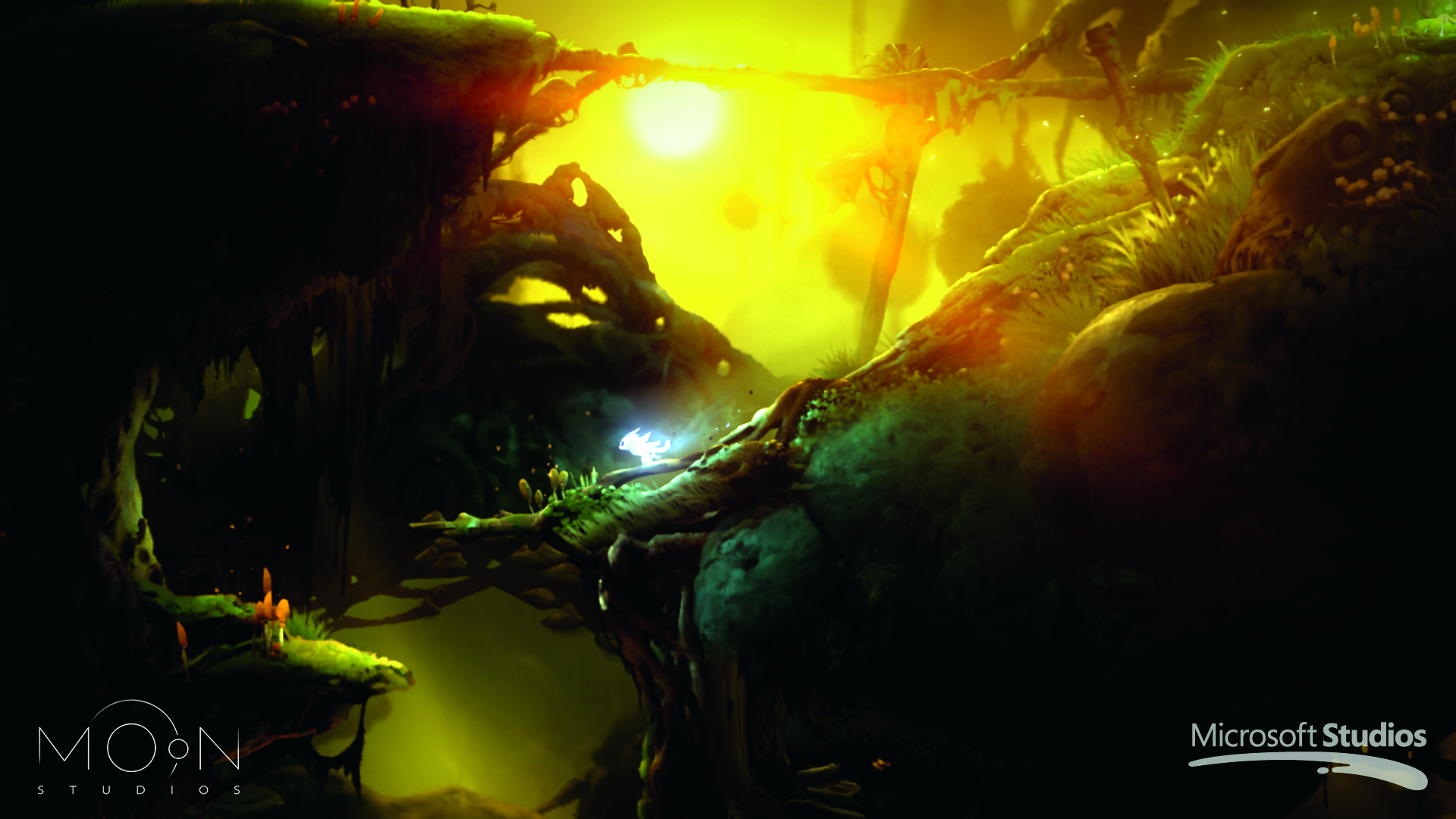

Working on a sequel presents an interesting challenge for game artists, in that they have to work with and develop an existing art style rather than crafting a new one.

When creating the look for Moon Studios’ Ori and the Will of the Wisps, art director and story lead Jeremy Gritton sought to stay true to the visual vocabulary of the game’s predecessor, Ori and the Blind Forest, while leading the art team to find new ways to put their own spin on the follow-up.

“This began by deconstructing the original game; really studying it to understand what they’d done, and why it worked,” Jeremy explains.

“Deconstruction is a very useful tool to go from appreciating something to understanding it. You might play a game and think, ‘I like the way this looks’, but breaking down all the components brings insight into the techniques that were used to elicit that feeling. If we were to follow in Blind Forest’s footsteps, we had to understand what they did and why it worked, so that we could both emulate and evolve it.”

Jeremy’s process for creating art for a level begins with making mind maps of ideas related to the core concept of the location, followed by a round of concept art to explore those ideas. “Defining a unique shape language is important, along with the chosen colour palette, because we want to create a memorable identity for each area,” he says.

“It’s difficult to dial everything in perfectly on the first pass, so I’m usually searching for something in our team’s work that grabs me, whether it’s the shapes or the colours that capture the feeling we want. As long as the potential is there in the initial concept, we continue iterating to develop the rest around the core element that was working.

“Story and art are a combination that’s very closely connected for me, so we always look for opportunities to inject environmental storytelling into our spaces. Striving to tell a story with visuals can provide another layer of heart and depth to the artwork.”

For games that have a more diffuse starting point, in that they’re not part of an established IP, and nor do they emanate from a single stroke-of genius artwork, the aura of the world is often built out of a collection of different influences.

For psychological thriller The Night is Grey, creative director André Broa and his team found inspiration in sources from other eras to feed the game’s dark atmosphere. “From the very beginning we liked the idea of The Night is Grey having the same vibe as children’s illustrated fairy tale books, as well as classically animated cartoons,” he says.

“The style of Don Bluth influenced us a lot when we were children and we wanted to bring that mix of cartoonish yet moody and kind of scary, like the tales of The Brothers Grimm. Those were the main themes, but lots of other works influenced us, from John Carpenter’s gore in The Thing to the painted background art style of Studio Ghibli.”

Exploring those earlier aesthetics was also the route taken by Alientrap creative director Jesse McGibney as his team went out in search of inspiration for Wytchwood, a game about playing the witch character in fairy tales.

“We looked to classic sources like medieval woodcut illustrations and the original fairy tales. We also looked at contemporary and familiar tellings of those stories, such as early Disney movies and character designs from Jim Henson’s Muppets,” Jesse says.

“We did a lot of mood pieces, concept art and sketches while in pre production, as well as developing our tool pipeline to figure out what would and wouldn’t work. Some of these technical limitations actually ended up enhancing the art style, such as the fact that everything is drawn on 2D cutouts, making the game look more like a pop-up storybook.”

Hitting the right artistic notes for a game level is more of a process than a destination. “Like most kinds of art, there’s no real point of completion, only a point at which you have to put it down and stop fussing with it,” Jesse adds.

“For game art especially, we’re constantly creating or improving our tools, which can mean we have to go back and redo previous sections of the game. Sometimes a level will start with a piece of concept art that we’re aiming to hit, or it might just be iterating on an idea until it feels right.

“For me, the most important thing I can do if something isn’t hitting right is to take a step away and come back to it later with fresh eyes. A lot of times, the things I have problems with will become more clear or will reveal themselves to not really be problems at all. But a lot of times you just have to call something done. Pretty much everything could be done better, but not if we ever want it finished.”

For more inspiration, see our features on video game art styles and the best indie game devs for inspiration.

This article originally appeared in ImagineFX. Subscribe to ImagineFX to never miss an issue. Print and digital subscriptions available.

Tanya is a writer covering art, design, and visual effects. She has 16 years of experience as a magazine journalist and has written for numerous publications including ImagineFX, 3D World, 3D Artist, Computer Arts, net magazine, and Creative Bloq. For Creative Bloq, she mostly writes about digital art and VFX.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.