Why Chronoscript's raw, hand-drawn art style is an inspiration

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Five times a week

CreativeBloq

Your daily dose of creative inspiration: unmissable art, design and tech news, reviews, expert commentary and buying advice.

Once a week

By Design

The design newsletter from Creative Bloq, bringing you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of graphic design, branding, typography and more.

Once a week

State of the Art

Our digital art newsletter is your go-to source for the latest news, trends, and inspiration from the worlds of art, illustration, 3D modelling, game design, animation, and beyond.

Seasonal (around events)

Brand Impact Awards

Make an impression. Sign up to learn more about this prestigious award scheme, which celebrates the best of branding.

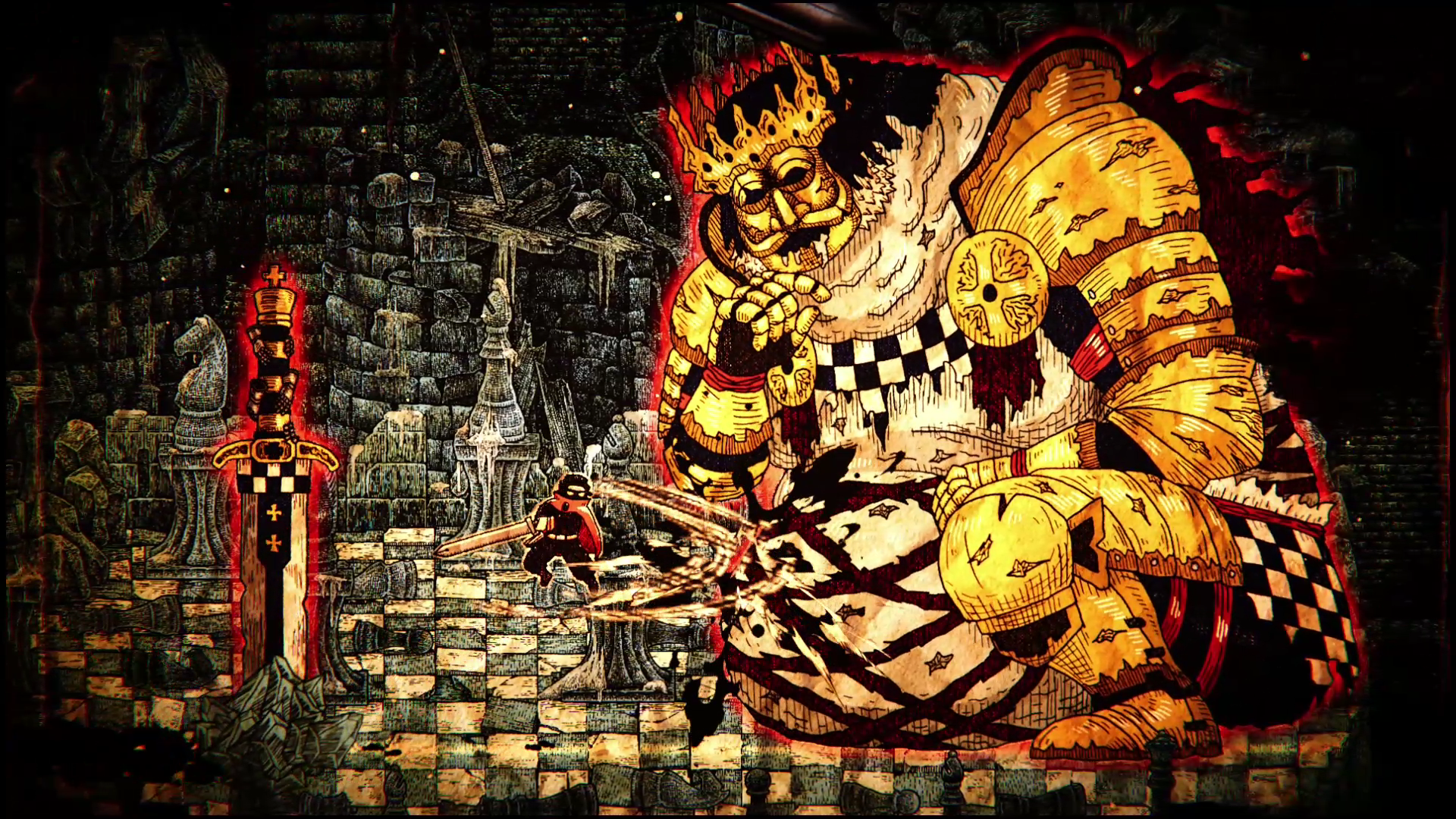

Sony’s latest State of Play was filled with spectacle, but amongst the juggernaut reveals like Wolverine, one indie game, Chronoscript: The Endless End, managed to cut through the noise. Announced for PlayStation 5 and Steam in 2026, this 2D action-adventure from DeskWorks and Shueisha Games doesn’t just promise an intriguing story about a cursed manuscript; it challenges how we think about game art itself.

Over the past decade, indie game aesthetics have polarised around two ideas. On one side, pixel art reigns supreme, embraced for its nostalgia and scalability in the likes of Shinobi: Art of Vengeance and Celeste. On the other hand, sophisticated 2D styles – the inky line art of Hollow Knight and the watercolour minimalism of Gris – dominate when indies aim for prestige. Both are familiar, both beautiful, but both carry an air of expectation.

Chronoscript rejects both. It doesn’t mimic 8-bit memory, old tech limitations, or polish itself into illustrative grandeur. Instead, Chronoscript embraces the messy, imperfect lines of hand-drawn sketching. Its world looks unstable, unrefined, alive in ways pixels and painterly washes often aren’t.

A manuscript that refuses to behave

The premise of Chronoscript, a protagonist trapped inside a never-ending book, could easily have been rendered in clean illustration or stylised typography. DeskWorks takes the harder road. Every page bleeds ink. Every enemy twitches with irregular strokes. Every environment feels like it was dashed off in a fever dream, then animated before it could be erased.

The result is not comfortable. It’s uncanny. The lines never settle, as though the manuscript itself resents being looked at. This is where the game’s uneasy world breathes: in the unsteadiness of the drawn line. And it’s where art and game design converge wonderfully.

Then there are the ruptures. While the 2D manuscript world dominates, Chronoscript occasionally tears its own rules apart, throwing players into jarring 3D sequences, cutscenes, boss strikes, and even rifts into the ‘real’ world. These moments aren’t just visual variety. They serve as a reminder that the ink can’t be contained, that the story you’re playing through is spilling into other dimensions.

The art of imperfection

Comparisons are inevitable. Vanillaware’s games, like Dragon’s Crown and Unicorn Overlord, are often held up as the pinnacle of hand-drawn 2D game art, polished into painterly perfection. Jason Roberts’ Gorogoa made the art itself the game (and took six years to make and paint). Clover Studio’s Okami turned brushwork into a playable aesthetic. But DeskWorks walks a different path. Their drawings don’t strive to be finished. They revel in the incomplete: strokes that tremble, figures that blur, ink stains that feel accidental.

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

Producer Masami Yamamoto describes the studio’s approach as “near-mad creativity”. That madness is the point. Where others chase smoothness, a finished, finessed look, DeskWorks chooses rawness.

Why it matters now

The games industry is in love with scale: bigger resolutions, denser detail, sharper lines. Against this backdrop, Chronoscript makes a radical case for the hand-drawn, the irregular, the flawed. It shows that imperfection can carry just as much emotional weight as fidelity, that sometimes, the trial and error, the misshaps and looseness, in an artist’s sketchbook can disturb and enchant more than a terabyte of rendered assets.

It also reasserts the value of process. When you see a smudged line or uneven shading in Chronoscript, you’re not looking at an error. You’re seeing the animator’s hand, the mark of their labour, and that’s something no algorithm or asset pack can replicate.

I always like to look behind the headlines at events like a Sony State of Play and see what games or ideas are hidden behind the latest Marvel tie-in, and Chronoscript: The Endless End is that game. It’s a challenge to players and creators alike to accept that games can be messy, human, and hand-drawn in ways that resist polish. Against the backdrop of Sony’s slate of polished AAA releases, this one really stands out, flaws and all.

Feel inspired, too? Read my guide to the best digital art software. Visit the Chronoscript website to find out more about this game.

Ian Dean is Editor, Digital Arts & 3D at Creative Bloq, and the former editor of many leading magazines. These titles included ImagineFX, 3D World and video game titles Play and Official PlayStation Magazine. Ian launched Xbox magazine X360 and edited PlayStation World. For Creative Bloq, Ian combines his experiences to bring the latest news on digital art, VFX and video games and tech, and in his spare time he doodles in Procreate, ArtRage, and Rebelle while finding time to play Xbox and PS5.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.