Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Five times a week

CreativeBloq

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Once a week

By Design

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Once a week

State of the Art

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Seasonal (around events)

Brand Impact Awards

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

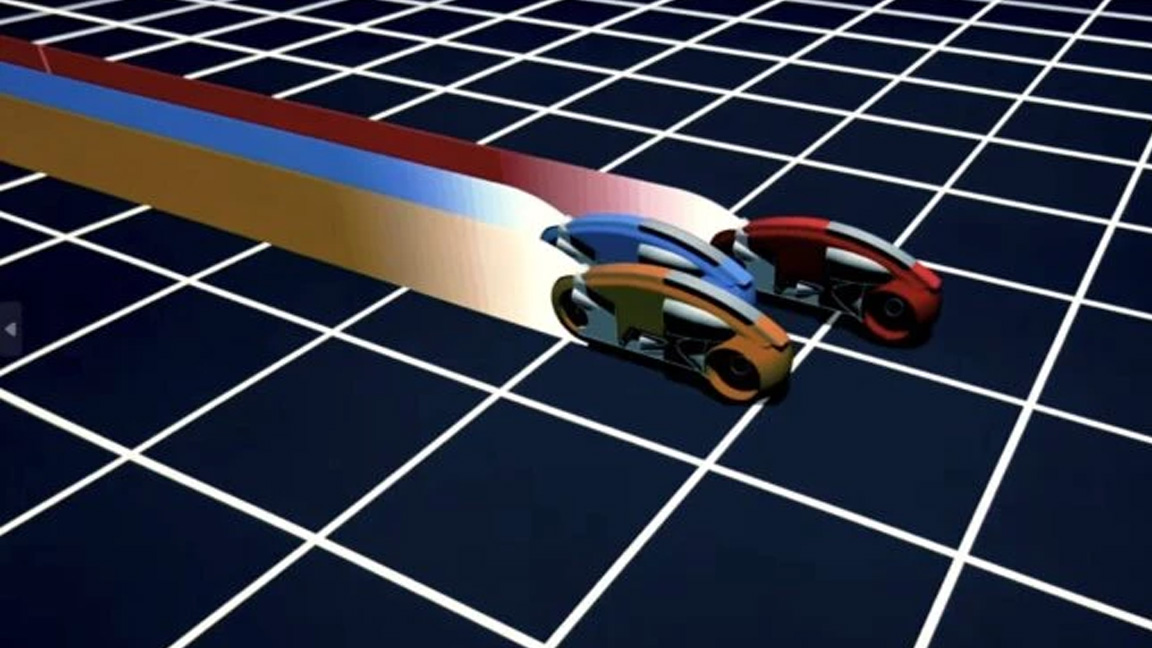

With TRON: Ares finally in cinemas, the digital frontier is glowing again (though a little dimmer than before). The news sent me back to the 1982 original, and honestly, rewatching it feels like discovering the moment cinema first embraced something new. Among the best CG films of the 1980s, a shortlist that barely existed at the time, TRON stands apart not just for its CG innovations, but for the sheer audacity of its vision.

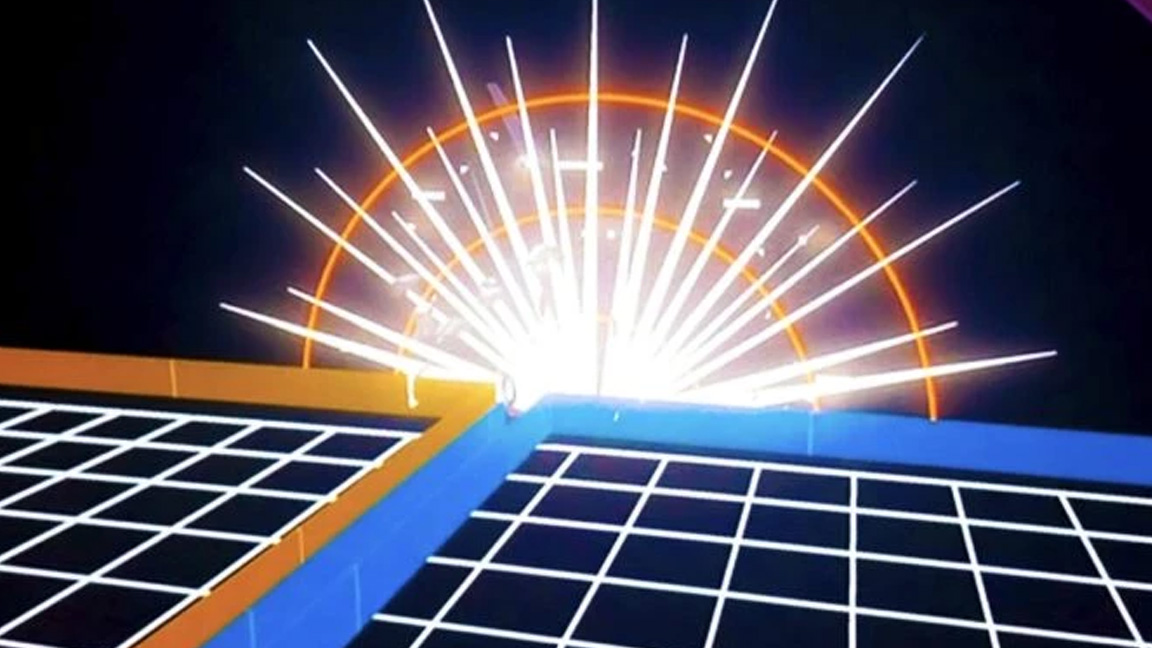

The film's neon grids, spinning light cycles, and crystalline landscapes might look primitive now, indeed, much of the movie relies on tried and trusted matte painting, but there’s a strange purity to them, a sense that this was the first time someone looked at a computer and thought, this is a place we could live in. Let's remember, this was peak Atari, arcades were destinations, and the world was just embracing video games.

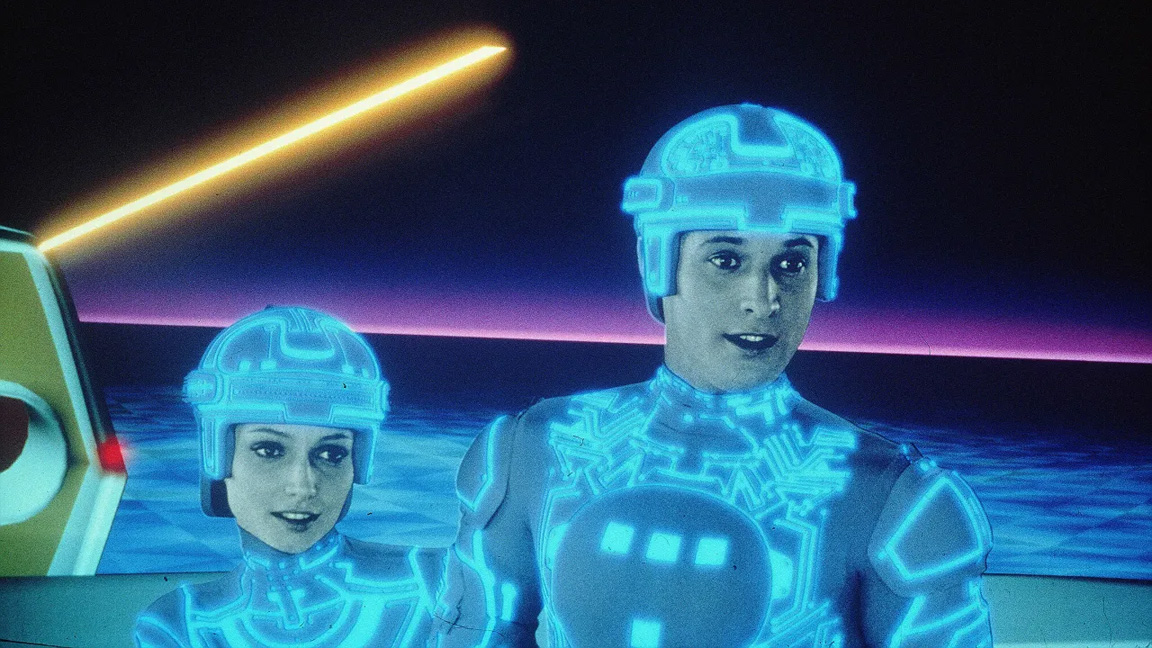

Yet despite its impressive experimentation with CG and computer animation, TRON wasn’t nominated for its digital effects. The Academy’s visual effects branch refused to recognise them, claiming that using computers was 'cheating'. Instead, its only Oscar nomination came for Best Costume Design. It sounds absurd until you realise that those suits, glowing and geometric, were far more than costumes. They were the first visual expression of life inside a machine.

Designing the digital body

In 1982, TRON’s creative team wasn’t just designing clothing; they were trying to design the future. Costume designer Rosanna Norton and futurist Syd Mead stripped away texture and mass, crafting sleek black suits traced with circuitry that glowed like living code. Every line of light represented energy, identity, and consciousness. The actors became data, and data became human.

Each costume was filmed in black and white, then coloured and composited by hand, a process that fused traditional craft and digital experimentation. The results were surreal, hypnotic, and impossible to categorise. These weren’t 'effects' in the Hollywood sense; they were a completely new design language, a bridge between animation, live action, and computer art.

It’s fitting, then, that TRON’s lone Oscar nod went to this handmade, human element. In a film built on technology, it was still the human touch that earned recognition.

Building a world before the tools existed

TRON was created before digital filmmaking had established rules. Its computer-generated sequences were built using multiple incompatible systems, with artists plotting points by hand and waiting hours for single frames to render. There were no modern compositing tools, no real-time previews, no safety nets. The production was a leap into the unknown, an experiment in making the invisible visible.

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Every pixel, every frame, was an act of imagination rendered in raw mathematics. That’s what made TRON not just one of the best CG films of the 1980s, but also one of the most influential, serving as the digital blueprint for everything from The Matrix to Ready Player One. (After seeing the movie, Disney animator John Lasseter founded Pixar two years later.)

So yes, TRON was recognised for its costumes, but what the Academy really acknowledged was a revolution in visual storytelling. Those suits gave a face to the virtual. They made cyberspace emotional. You can trace TRON’s DNA through motion graphics, UI design, and the entire cyberpunk aesthetic.

The TRON design legacy

But now, as TRON: Ares prepares to expand that universe, it’s impossible not to see the parallels with today’s creative tension around AI in filmmaking. In 1982, the Academy dismissed computer graphics as too artificial, too machine-driven. Sound familiar?

We’re having the same conversation now, only this time, it’s about AI models like Sora 2 that can write scripts, animate characters, and generate imagery. Are they tools for artists, or replacements for them? Should creativity be celebrated when it’s machine-assisted, or condemned for being too easy? The echoes of 1982 are louder than ever.

Will we be here again in forty years, looking back at the first wave of AI-driven cinema the same way we now look at TRON, the misunderstood outlier that changed everything? I've spoken to many AI filmmakers, some established, and they all see AI as a creative tool. Spike Jonze's surreal Gucci movie shows how filmmakers can really use AI, too.

More than four decades later, TRON still feels like a moment the film industry stopped and changed direction, just as it had done years earlier when Oz was colourised and Mary Poppins danced with animated animals.

That’s why it deserves to be part of today’s AI conversation. If we've learned anything from TRON's effects, from its blend of design, costumes, and CG, it's that human creativity needs to remain in the mix, but if history repeats itself, we’ll once again see artists accused of cheating, right up until their work redefines what creativity means.

Ian Dean is Editor, Digital Arts & 3D at Creative Bloq, and the former editor of many leading magazines. These titles included ImagineFX, 3D World and video game titles Play and Official PlayStation Magazine. Ian launched Xbox magazine X360 and edited PlayStation World. For Creative Bloq, Ian combines his experiences to bring the latest news on digital art, VFX and video games and tech, and in his spare time he doodles in Procreate, ArtRage, and Rebelle while finding time to play Xbox and PS5.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.