Hand vs machine: What’s the future of print design in fashion?

From painting florals to scanning brains

In fashion studios worldwide, a creative evolution continues to reshape print design. While some designers manipulate pixels on screens, others insist on paint-loaded brushes. This tension defines one of fashion's biggest creative developments: the shift from analogue to digital processes in print design.

However, far from a simple case of replacing old with new, it’s a complex dance between tradition and innovation, craftsmanship and efficiency, artistic expression and commercial demands. Some of the most influential fashion trends have balanced the old and the new.

And as AI increasingly encroaches on the industry as a digital tool, how should designers navigate hybrid models to bring designs to life? Designers and fashion educators weigh in.

Analogue legacies

“Printed textile design really developed through the industrial revolution, prior to this, pattern and imagery on garments would have been achieved through weave and embroidery. Copper plate printing, which was used to create toile de jouy, was the first invention, where an image was engraved onto copper, the different depths of the incised lines creating tonal qualities in a single colour. This method was industrialised and the plate became a roller and roller printing,” says Professor Amanda Briggs-Goode, head of department for fashion, textiles and knitwear and director of the Fashion and Textile Research Centre at Nottingham Trent University.

“Another method of the 19th century was block printing, used well into the 20th century, where each colour of a design is carved into a wooden flat block and then lined up and printed as a repeat – a method best known in the work of William Morris.”

“The real game changer came in the 1920s with the beginning of screen printing, where the translation of a design idea was more under the control of the designer and achieved photographically,” Amanda continues, describing how this is done both by hand and in rotary screen printing, the latter being how the majority of textiles are printed in industrial settings today.

Beyond this, since the 1990s, digital printing methods have been emerging and opening up the use of colour without limits, she adds, although this method still represents a relatively small percent of global production.

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

The hands-on resistance

Despite the pace of digital development, analogue approaches embody a fundamental belief in the value of the human touch. “Print designers are really driven by drawing, mark making and the use of a sketchbook, where you develop your own handwriting and explore ideas – these are still important visual research methods for designers,” Amanda says.

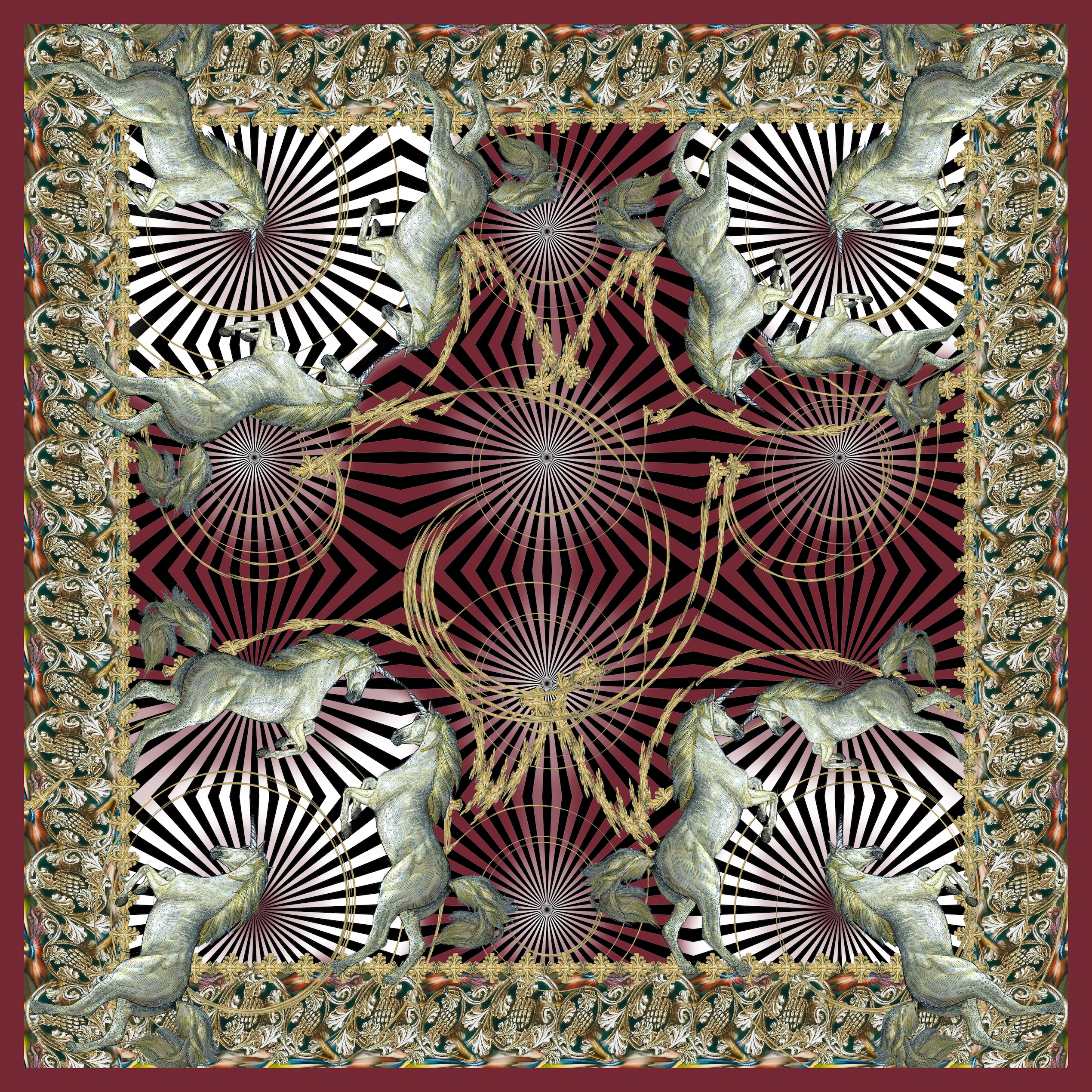

For Swiss artist and designer Ginny Litscher, the creative process of print design remains deeply rooted in physical techniques to produce her intricate designs, which are printed on silk scarves, bathing suits, cushions and other garments. “My artwork is always hand-painted or hand-drawn by me. And I enjoy mixing techniques,” she says. “First there is an intuitive image that pops up naturally in my head. The colours and details are already clear, as I have a photographic brain. Then I go to work. Often, I start painting on a big canvas – with brushes, pencils, ink, oil. For more detail I like to work with ink, and oil to make the colors pop.” Like many of her peers, Ginny then digitises the work by photographing or scanning it into Photoshop in order to prepare the print file for production.

The tactile nature of these traditional techniques influence the final aesthetic of designs in ways that digital tools still struggle to replicate authentically. The unpredictable material nature of ink bleeds and brush stroke textures and the happy accidents that occur during production contribute qualities that many designers consider irreplaceable.

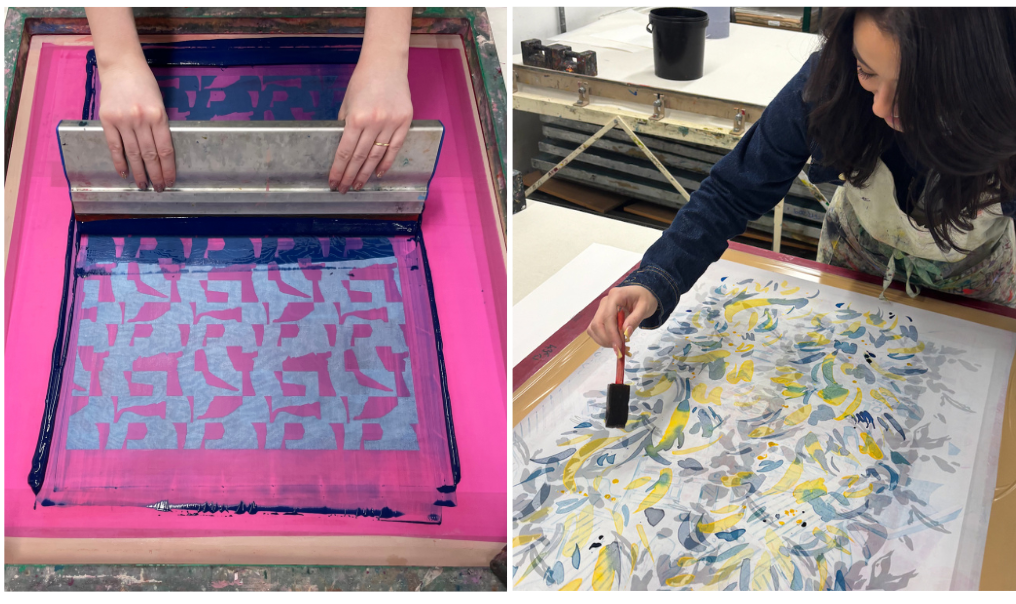

Sarah Cheyne, senior lecturer in design and print at UAL London College of Fashion advocates for what she calls “a hand-crafted approach rooted in drawing, mark-making and craft techniques” – a philosophy that reflects a broader educational movement recognising the value of hands-on skills, even in the digital age. “I love exploring drawing and painting, hand-crafted techniques and using these as a basis for design directions, also mixing with photography, especially cyanotype photography [a camera-less photographic printing process],” she says.

The digital takeover

However, Sarah says that at the same time she also encourages embracing digital processes in the development of ideas, with the aim of pioneering experimental techniques to create innovation. “Over the last 25 years digital software such as Photoshop and more recently AVA CADCAM have revolutionised the design process to make design and colour development much quicker and easier for designers,” she says, which initially resulted in an increase in designs with an overly “digital” appearance.

Gareth Wadkin, course leader for the BA in textile design at Leeds Arts University, agrees that there has been a fundamental shift in how many designers conceive and execute their visions in recent decades. “The rise of digital textile practices has transformed how designers approach colour, detail and production. Advances in digital software offer precise colour control, image manipulation and the ability to create complex repeat patterns and layered textures, enabling professional-standard designs for print. Digital printing allows for rapid prototyping and sampling, making it easier to test ideas efficiently,” he says.

The speed of digital iteration has compressed design cycles dramatically, Gareth adds. “Unlike traditional methods such as screen printing, which require separate screens for each colour, digital processes offer greater speed, flexibility, and an almost limitless colour range. Rather than replacing traditional techniques, digital methods complement them." Combining digital fluency with hands-on processes such as screen printing, dyeing and embroidery, is the best way to gain a comprehensive understanding of textile design and production, Gareth says, particularly in an ever-evolving industry.

The freedom gained through digital tools has democratised print design, enabling independent designers such as Matt and Lauren Rowley, co-founders of UK-based streetwear brand ATTREN, to compete with established labels. Although they originally spent time seeking inspiration in London (“taking photos of anything that inspired us – colours, landmarks, clothes, stores, people in the street,” Matt says, then sketching out ideas) they decided to collaborate with an artist to elevate garments.

Their collaborative approach with graffiti artist Julian Johnson aka ArtJaz exemplifies how digital tools can preserve artistic integrity while streamlining manufacturing.

“We were lucky as Julian produced all of his work in Illustrator so it was as close as possible to be ready for print,” Matt says of the designs, which needed just a bit of tweaking before finalising for samples. “Each collaboration collection is named after the artist [and] each artist comes up with that character in their own style. Julian produced Big Tony and Lil Flo and we fell in love and knew they would be our first release. The art was so good we put it as big as we could on the back of the tees and jackets.”

The hybrid debate

ATTREN, though using digital tools for conception, uses screen printing when producing the design: “We felt screen printing would bring out the best in the art and give it some texture,” Matt says.

This highlights a common debate when it comes to analogue versus digital, around perceptions of quality, though viewpoints and definitions vary significantly. Traditional screen printing enthusiasts, for instance, will often argue for its tactile quality and superior colour saturation and durability.

However, digital printing’s quality has evolved dramatically, with photorealistic imagery and complex colour gradations offering increased precision and repeat accuracy. This also helps boost digital printing’s sustainability goals – precise colour matching aiming to minimise reprinting and on-demand printing for decreasing overproduction, for example – though energy consumption and equipment lifecycle also present ongoing challenges.

Alongside, the idea of digital freedom, while liberating, can become a paradox, overwhelming designers with infinite possibilities – Adobe Creative Suite, NedGraphics, specialised CAD programmes, the rise of AI. Once complex repeat patterns and sophisticated designs are more easily (and endlessly) automated via simulation. This, in turn, could reduce intuitive problem-solving that traditional constraints encourage.

Sarah advocates for a balanced approach: “I think it is important to train designers who can handle both analogue and digital methods as this combination of skills is expected in the workplace.”

Gareth agrees that a hybrid philosophy recognises that each approach offers distinct advantages: “Digitally printed textiles are increasingly popular, supported by access to innovative technologies and industry-standard software such as Adobe Photoshop and Illustrator,” he says, allowing designers to explore more complex design possibilities. But it is still important to engage with a wide range of surface and print techniques, he adds, including screen printing, sublimation, heat transfer and laser cutting. “This comprehensive approach encourages experimentation with texture, layering and materiality, fostering a strong understanding of both aesthetic and technical aspects of textile creation.”

What’s next

The analogue versus digital debate becomes more complex as new technologies emerge – particularly as AI increasingly impacts print design through the possibility of trend prediction algorithms and automated pattern generation. However, across the design industries more widely, AI is being seen as a tool or a co-pilot rather than a creator in itself.

Pushing beyond the techniques described above, smart textiles represent print design’s next frontier – patterns that change colour based on temperature, respond to touch or shift through programmed sequences, for example. The landscape is continuing to expand and designers are embracing both analogue and digital processes to create increasingly unique designs.

Kuo Wei, designer and founder of Taiwan-based clothing brand INF, for instance, recently used his own brain MRI images in his designs, which were transformed into a subtle print that featured on garments for the Spring/Summer 2025 collection.

The idea stemmed from Wei being asked, ‘“How did you come up with those designs and what exactly is in your brain?”,’ he says. “Since the SS25 collection is reaching the peak of transformation design for INF – such as a T-shirt that turns into a tote bag, a skirt into trousers, a dress into a top – I figured why not also answer people by showing them my brain?” Wei says. “I took my brain MRI image as the foundation texture for the print design and added several touches, such as blurring, diffusing, rotating and flipping, to produce the print now you see on the pieces.”

For more on the interplay between fashion and graphic design, check out this recent piece – covering everything from visual identities to gamification – and the most iconic trends in fashion from the last 50 years, as picked by experts.

Antonia Wilson is a freelance writer and editor. Previous roles have included staff writer for Creative Review magazine, travel reporter for the Guardian, deputy editor of Beau Monde Traveller magazine, alongside writing for The Observer, National Geographic Traveller, Essentialist and Eco-Age, among others. She has also been a freelance editor for Vogue and Google, and works with a variety of global and emerging brands on sustainability messaging and other copywriting and editing projects — from Ugg and Ferragamo to Microsoft and Tate Galleries.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.