Fifty years ago, The Rocky Horror Picture Show burst onto the big screen in an explosion of camp rock, B-movie sci-fi nonsense and stockings and suspenders. Late-night screenings and audience participation turned into much more than a movie: a cult phenomenon that lives on today.

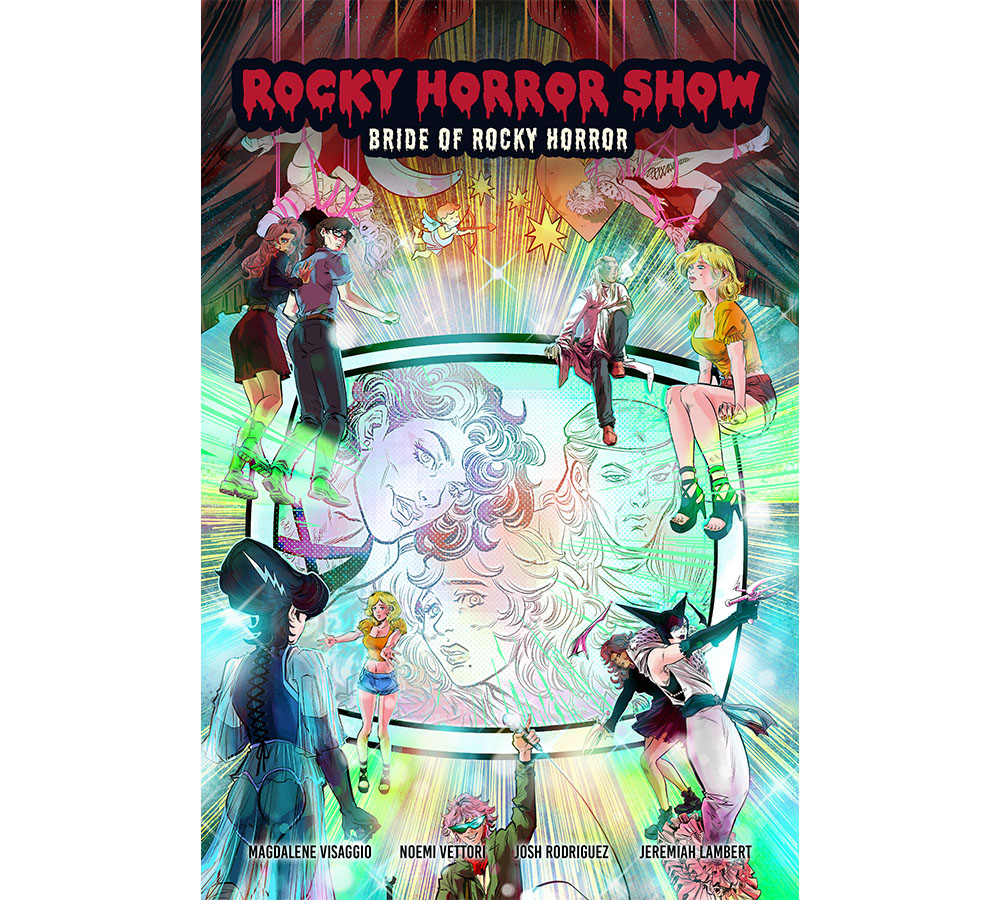

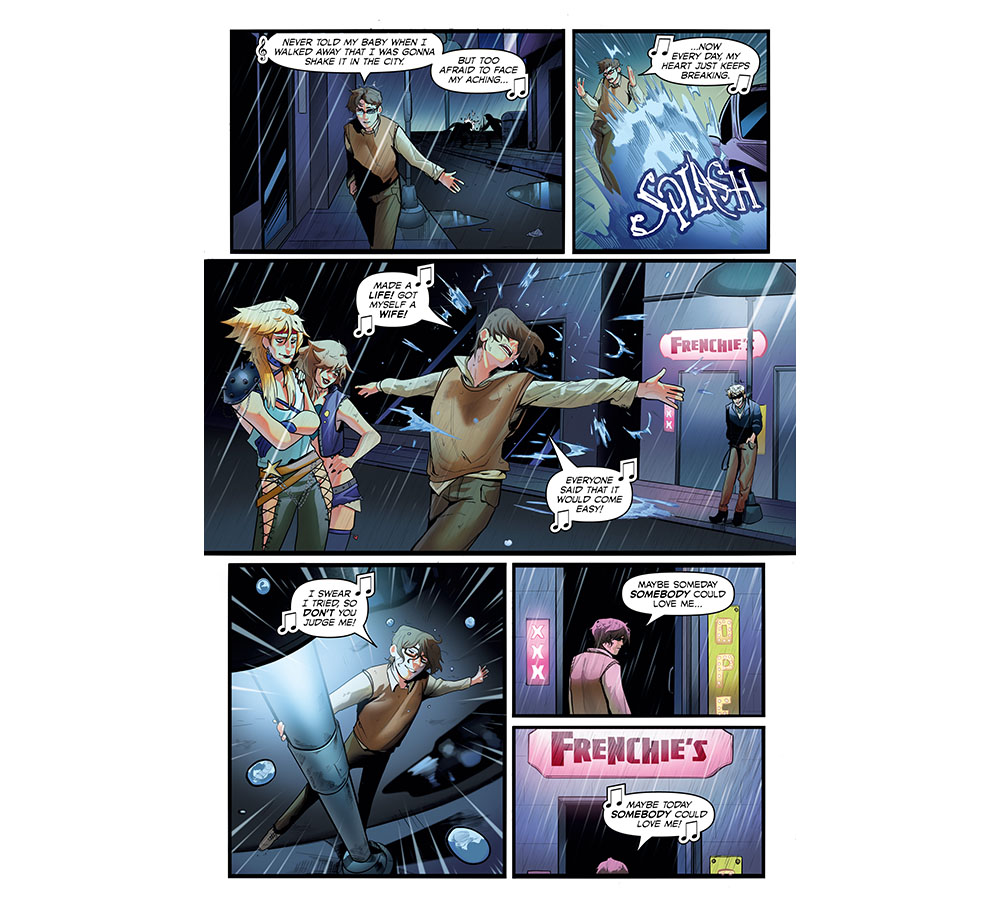

Despite that legacy, it never became a franchise, although Richard O'Brien made Shock Treatment as an offshoot. But now an officially licensed graphic novel continues the story. Written by Magdalene “Mags” Visaggio, the writer of Girlmode, and with art work by X-Men Unlimited illustrator Noemi Vettori, Rocky Horror Show: Bride of Rocky Horror sees Brad and Janet get sucked into the time warp again.

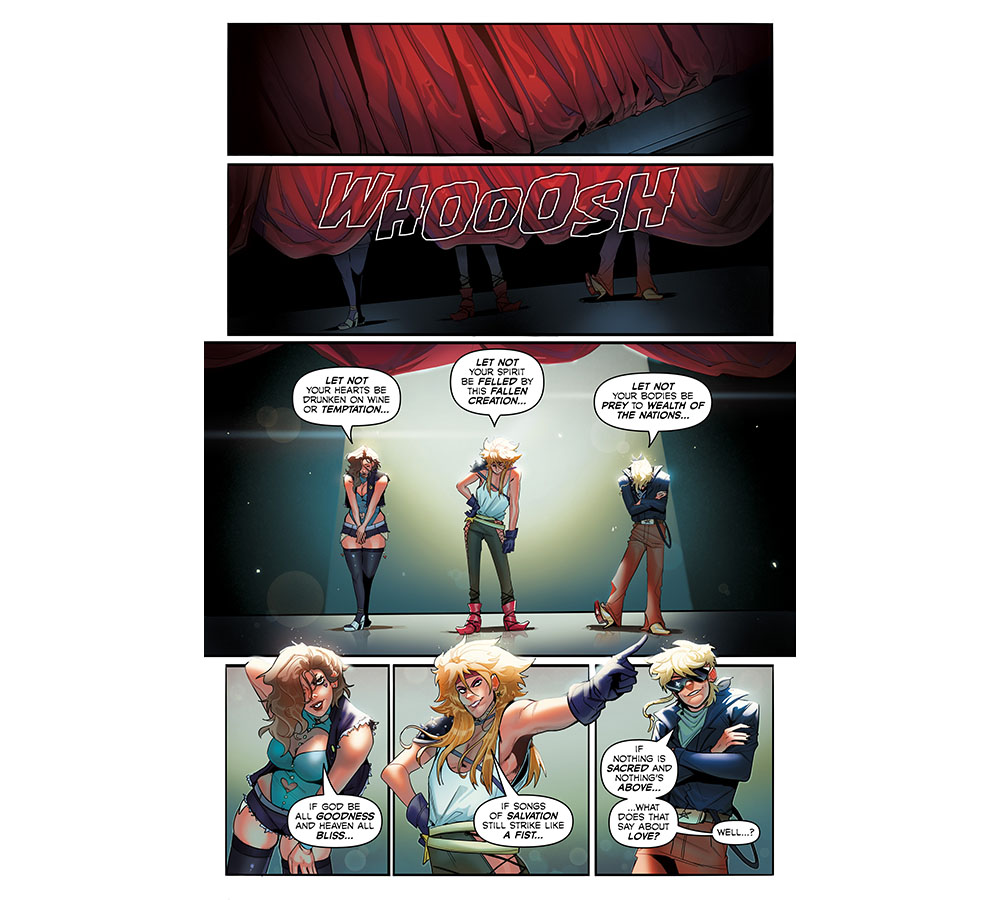

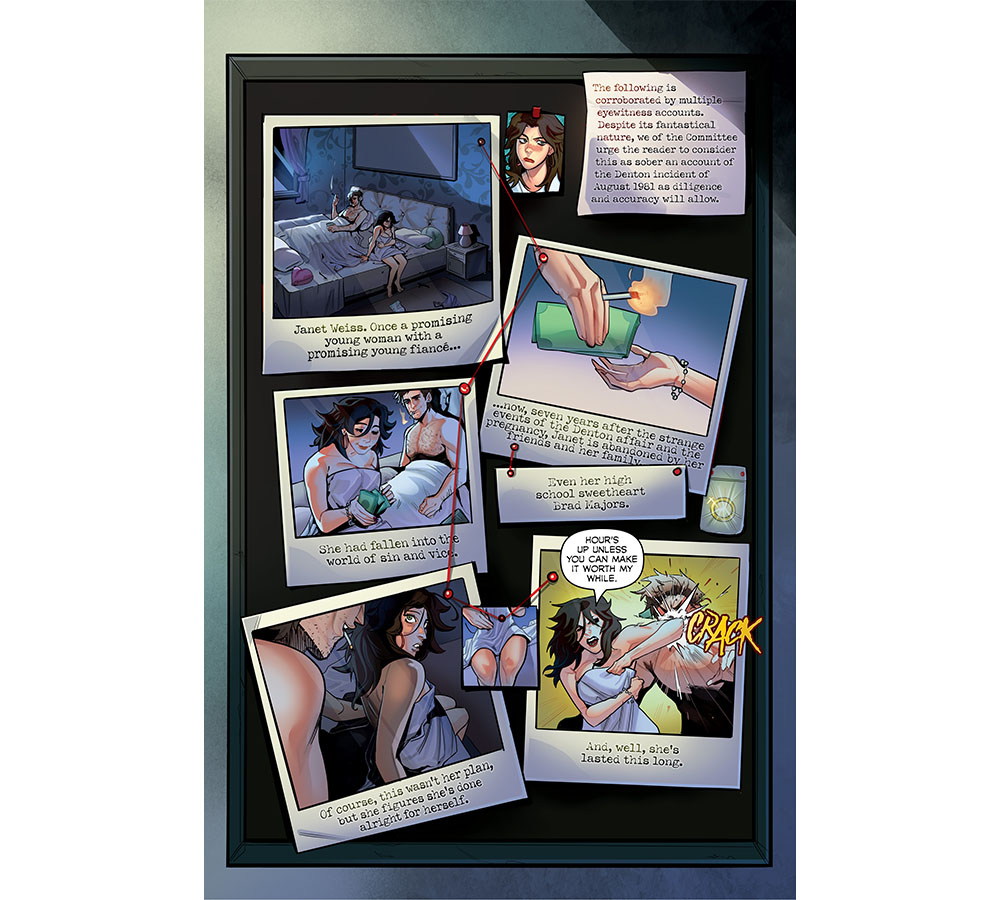

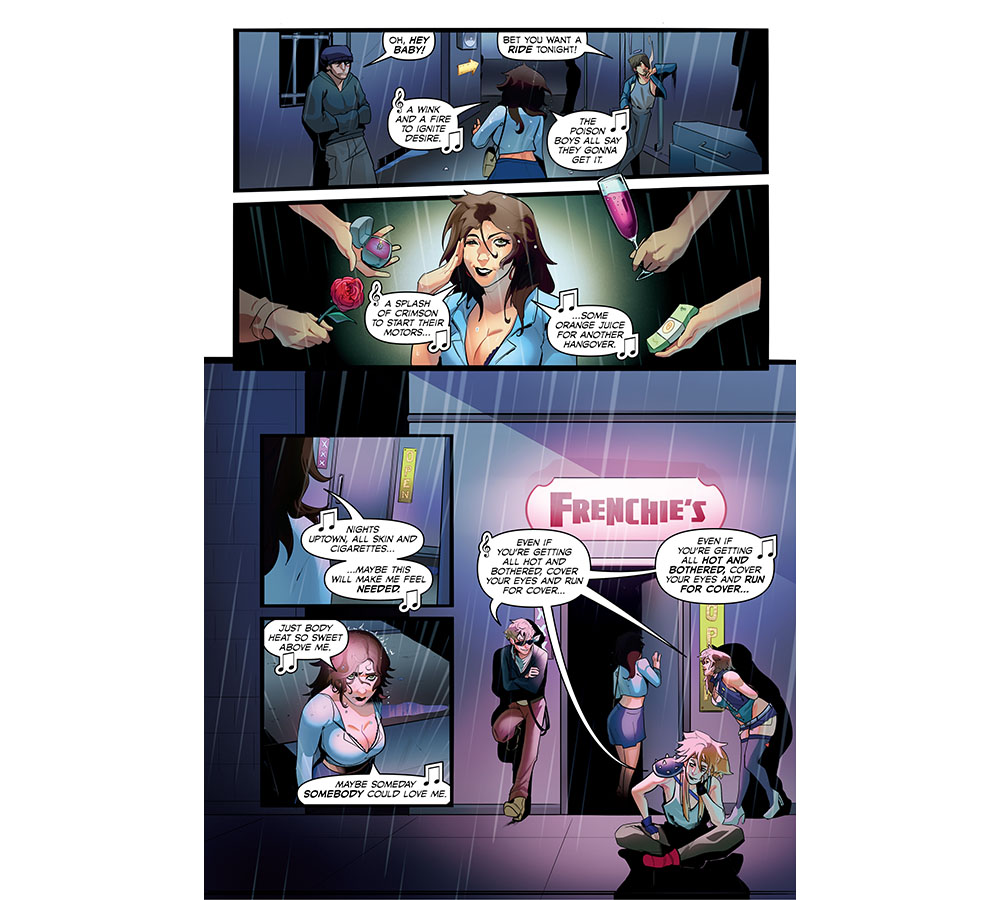

With society so different today, I asked Mags how she approached the task of adapting Rocky Horror to comic form. The interview is illustrated with pages from the graphic novel, which is being published by Bit Bot Media.

Fifty years on from the movie, why is The Rocky Horror Picture Show still so popular?

Is this a trick question? Why is Star Wars so popular today? Rocky Horror endures because Rocky Horror is fun as hell, first of all, and because it never really ended. It turned into something bigger than itself the very same way as something like Star Wars: by moving off the screen and into the real world.

I don’t mean that in a flippant way, either, or in some hazy metaphorical one about, I don’t know, how it lives in our hearts or some dumb shit like that. It moved into the real world by becoming something people did and not just something they liked. That’s the formal definition of a cultus, which is where we get the words cult and culture. A community bounded by commonality that renews itself by retelling the story.

Richard O'Brien's plans for a direct film sequel never came to fruition. Why do you think a graphic novel is the right format to continue the story?

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

I don’t. Full stop. It’s a graphic novel because I’m a graphic novelist and that’s what I was hired to make, but Rocky Horror ain’t Rocky Horror without the music.

Comics are their own thing, and maybe I do the book a disservice by comparing it so much to a completely different medium that allows for completely different species of expression. I always like to say that comics should be comics, and not try to be something else, and here I am giving you a comic book that’s also a musical? I don’t know. It’s Rocky Horror. What else was it supposed to be?

I ask myself sometimes, well, how would Grant Morrison approach this? And they’d make something that was representative of the spirit of Rocky Horror that played to the particular strengths of comics in ways I think might have made it unrecognizable. I didn’t want to make it unrecognizable.

I wanted it to be Rocky Horror. And Rocky Horror is glam rock. So…yeah. No, I don’t think this is the best format for a sequel to that particular movie, but I jumped at the chance to do something new with these characters and these ideas and these horrible, wonderful things that happen when they collide.

Given the original movie's cult following, how did you balance respecting the original while doing something new?

I didn’t. Please don’t think I’m trying to be difficult with your lovely questions! But Rocky Horror is, by far, my favorite movie. I’ve seen it way more often than any other, and it’s not a close contest. I know it inside and out. So I wasn’t worried about respecting it. The truth is that my take isn’t going to satisfy everyone, because nothing can. All I could do was the same thing Richard O’Brien did: tell the story I wanted to tell.

As much as I could, I tried to channel O’Brien’s unique voice, but that’s obviously not possible; he is sui generis, irrepeatable. I tried to keep the camp, the fun, the brazen goofiness of its ostensible “science fiction” trappings, that whimsically loose plotting where nothing really happens but it’s all happening so fast you don’t even notice until it’s over and most everyone is dead. God, what a show! It never stops, not for one goddamn second. It never gives you time to sit and think about it too much.

But I am not Richard O’Brien, and as much as I tried to capture the tone of his (and Jim Sharman’s) insane genius, it was Mags Visaggio at the keyboard this time. I have different preoccupations, not the least of which is that O’Brien is forty years older than me. He grew up watching all those old B sci-fi movies in the fifties and sixties.

But I grew up in the nineties; my experience of sci-fi is different, my experience of queerness is different. I have a specific education in literature, philosophy, and theology that O’Brien doesn’t because he went to different schools and studied different things. I grew up playing video games. He didn’t. So, no matter what, this was never going to be Richard O’Brien’s Rocky Horror.

I am acutely aware that this is the only licensed sequel to Rocky Horror, and that nobody has been allowed to play in this sandbox before. There’s not decades of tie-in books, or a whole Rocky Horror Expanded Universe. This is the first time a different authorial voice has ever had the reins. And I recognize that some people might see that as a responsibility. I don’t. I see it as a chance.

Fifty years of Rocky Horror. That’s fifty years where it has been part of the culture it was responding to. Fifty years of history for LGBTQ people. AIDS happened. And if I’m the first person who gets to do something additive to Rocky Horror, something really truly additive, that means I’m the first person who gets to stand on the other side of those fifty years and think about what this kind of story is even for today.

The world is a wildly different place, and so much of what Rocky Horror treats as taboo deliciously ignored is now just daily life for millions of ordinary folk. So really, I wanted to do a Rocky Horror about what happened after Rocky Horror, both for Brad and Janet and for the wider world at large.

Brad and Janet end that strange night in the castle having been forced to confront things about themselves that would have demanded some kind of response, some kind of choice about what to do with what they learned. That meant thinking about, okay, what did they learn? What exactly happened to them there, globally speaking?

Now, I have written about this at considerable length in Feminist Press’s Absolute Pleasure: Queer Perspectives on Rocky Horror, and everyone should go read that whole marvelous collection, so I’ll be brief: Janet experiences the events of that night as liberation, of a coming-into-herself and her sexuality.

But not Brad. Never Brad. Brad stared into the dark eyes of desire and saw something that terrified him. What I posit is that Janet chose to be honest about what happened, and Brad chose not to.

This destroyed their engagement, and now seven years have passed. Time has done its work on both of them. So when they get sucked back into the ol’ Time Warp, well, these aren’t the same two kids. Their time there changed them, as it changed all of us who found it at the right or wrong moment.

We're there any challenges in adapting Rocky Horror to a comic format?

It’s not a particularly complex story – that’s part of what makes it work so goddamn well. It’s a stock plot with stock characters filtered through a specific kind of experience that looks a lot like madness.

Brad and Janet are just the All-American Couple. Brad’s tall and square-jawed and looks a lot like Superman. Janet’s smaller and mousy and has this delicate voice and she’s always hiding behind her man, at least at first. Standard stuff.

They get trapped in a weird castle with a mad scientist with a mad creation. A stock plot, like I said, and easy enough for a comic book. I didn’t want to just remake Rocky Horror, but I wanted to keep the recognizable shape of a stock plot, and so: Brad and Janet are kidnapped by aliens who want to do weird experiments to them. Easy peasy.

And the themes – forbidden knowledge, taboo sexuality, madness, violence, murder – these are comic book standards. Comics are not some unique medium that can only handle so much; it’s been a thriving medium for over a century, and it is endlessly plastic. It can give us The Yellow Kid and Moebius, WicDiv and Blankets. So there wasn’t a challenge there, either.

Honestly the most difficult thing was capturing the madcap pacing. It’s almost screwball, it moves so fast. Nothing lingers. Frank ushers them from room to room without much in the way of intention or direction, and then a bunch of people die. I struggled quite a bit with plotting this loose, and I’m still a little worried the end result is too structured, too…formally coherent to really fly the way Rocky Horror does.

Have you ever seen a TV show where we have to see a “bad drawing?” Like a kid’s drawing? Except the person who drew it was clearly an adult with real artistic training, and so it doesn’t look like a kid did it, and it just looks weird and wrong and stupid. Rocky Horror is just relentless in its forward motion even though it’s never entirely clear why any of these things are happening.

The truth is that it doesn’t matter, and that it would get in the way of what the show really is doing: putting Brad and Janet through the emotional and sexual ringer to see what happens. God it’s so insane. There’s incest. Cannibalism. Shock after shock after shock. Eddie shows up and immediately gets killed. Absolute pleasure? More like absolute madness.

I’ve got all this stupid training in literature and craft and I had to fight so many of those instincts tooth and nail to make it feel right, which meant draft after draft after draft, stripping the plot down further and further until it moved with the same crazy energy.

You can order Rocky Horror Show: Bride of Rocky Horror via Kickstarter.

For more inspiration, see our recent interview with book cover author Dan dos Santos about the importance of sketching.

Joe is a regular freelance journalist and editor at Creative Bloq. He writes news, features and buying guides and keeps track of the best equipment and software for creatives, from video editing programs to monitors and accessories. A veteran news writer and photographer, he now works as a project manager at the London and Buenos Aires-based design, production and branding agency Hermana Creatives. There he manages a team of designers, photographers and video editors who specialise in producing visual content and design assets for the hospitality sector. He also dances Argentine tango.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.