Suda51 explains his creative chaos: "We make our games through a lot of ad-libbing"

If you've played a Grasshopper Manufacture game, then you'll know that the Tokyo-based studio has a distinctive visual style that aptly expresses its company ethos, 'Punk's not dead'. Its latest game, Romeo is a Deadman, is perhaps its boldest and most bombastic vision yet.

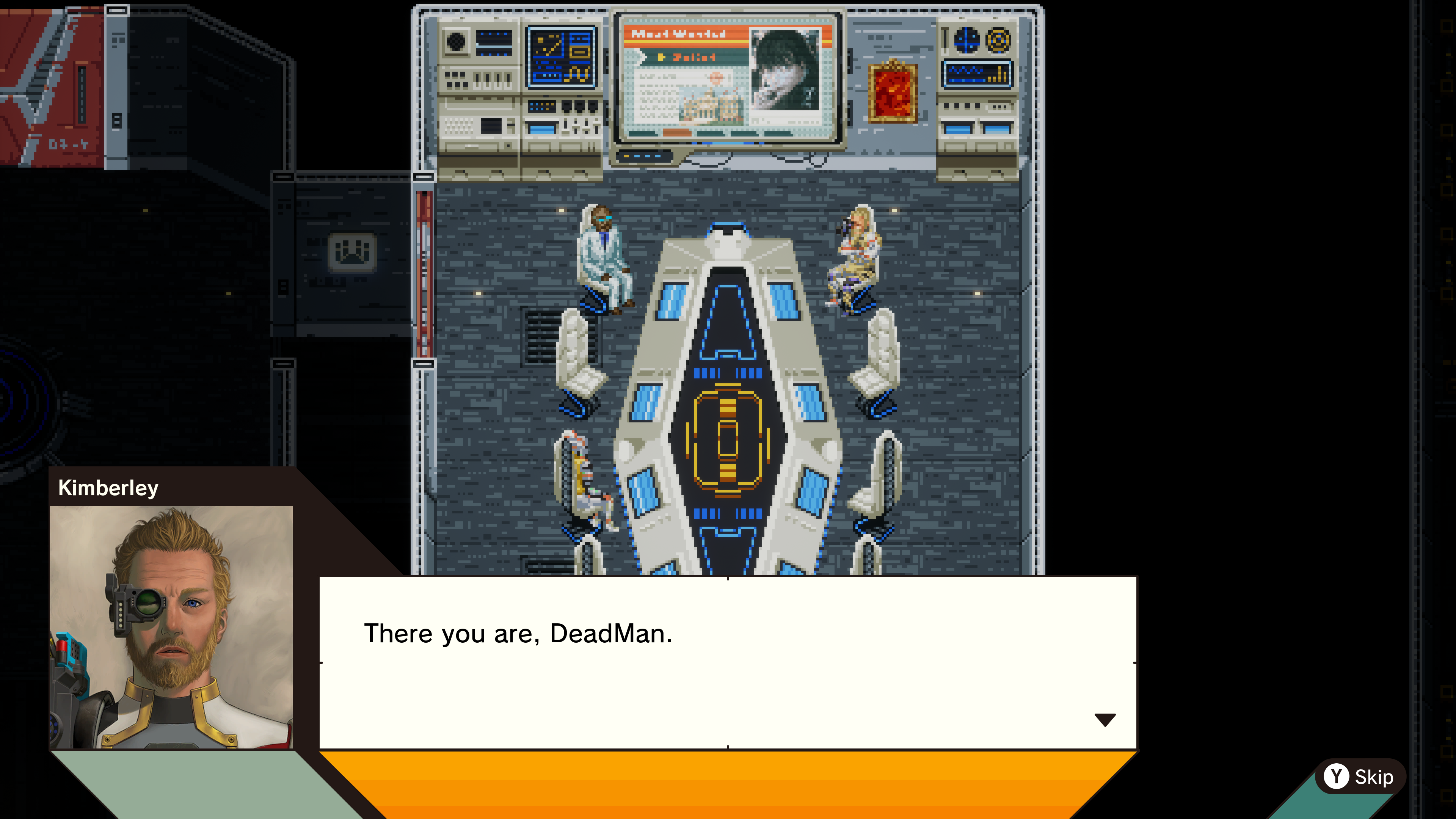

Even in just the first 20 minutes, as protagonist Romeo Stargazer goes from a small-town young sheriff's deputy to surviving a horrific, fatal attack by becoming a cybernetic action hero who can travel through space-time, I'm already dizzy with the different art styles I've been bombarded with: stop-motion, comic-book, pixel-art, anime, and even what you could call live-action.

There's also a schizophrenic smorgasbord of cultural references, from Shakespeare – there is of course a Juliet in this story, albeit one who may consist of multiple identities across space-time – to Edward Hopper, The Clash, Gundam, Back to the Future, Tron, and of course other games, from Pong to Pokemon, even some deliberate nods to Grasshopper's past games.

If this everything-but-the-kitchen-sink approach sounds unruly and chaotic, it does define Grasshopper's style and the way the studio has always worked, according to its founder and CEO, Goichi Suda, also known to fans as Suda51.

The improper way to make games

"Most studios, triple-A or even indie, you could probably say that they make their games ‘properly’ – they come up with, and they have a blueprint for the game," Suda tells me, as translated by Grasshopper community manager James Mountain. "Conversely, at Grasshopper, I guess you could say we develop games improperly. It's something that I just kind of refer to as ad-lib development."

That is to say that instead of having meetings with the leads where a clear design document comes together, he goes on to say that the studio's meetings can vary, from "a bunch of people, or just a few people … Even in those meetings, the stuff that gets discussed, the ideas that come out, they could be something completely unrelated to what we're originally talking about."

Even though longtime Grasshopper member Ren Yamazaki is credited as the director of Romeo is a Deadman, the vision is still very much Suda's, who describes the game as "a bit more complicated than usual" as he wears the hats of producing, writing, and co-directing. "I actually ended up spending a lot more time together with developers of different parts of the game than I have with my last few titles."

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

It also means he's very conscious of the game's budget, which is also a reason behind the many different visual directions. Although the core action gameplay does employ a photorealistic style achieved with Unreal Engine 5, it still turns into a psychedelic dancefloor when unleashing a special move, or the puzzle sections are set in a blocky Tron-like subspace. Unreal Engine 5 may make stunning photorealism easier to achieve, but cost remains a factor.

"As technology advances, it's been more and more expensive to make a game with all 3D graphics," Suda explains. Without getting too specific on the numbers, while also trying to factor in exchange rates and inflation, let's just say the figures he gives for how much 60 minutes of full 3D polygon cutscenes in the first No More Heroes back in the Wii era would cost, compared with the same amount for its third instalment made originally for the Switch, and now Romeo is a Deadman keep ballooning substantially. Exploring different visual styles has been a shrewd cost-saving measure, both in terms of money and time.

For instance, there's a scene towards the end of the game that Suda had envisioned differently, but ultimately used the retro green-and-black pixel art previously used for the visual novel element of Travis Strikes Again. "That was getting kind of near the back end of the schedule, and when we start getting into crunch time, if I'm asking for these new assets, the people doing the actual programming and art tend to get pissed," he explains. "So just porting that one part from TSA over and making use of that art style instead, it just made everybody's lives easier."

Mixing practical and pixel art

While it also makes sense to leverage the different skill sets of existing team members for different art styles, there were also times when it made sense to outsource the work through personal connections, such as the pixel art for the interior of your hub ship, which was handled by a company called Hattori Graphics. Another outstanding piece of work handled externally was Romeo's death sequence, as you watch his already mutilated face melting in horrific Raiders of the Lost Ark fashion, and which was similarly achieved with practical effects.

"For Romeo's death scene, I'd written out how I wanted it to look, but if we tried to do it just using computer graphics, it would just look kind of funky," Suda explains. "Our lead artist just happened to mention in conversation one day that they have this friend, Tomo Hyakutake, who's really good at doing realistic-looking practical effects and special makeup, so we outsourced this for him to take care of. So we have people participate in some parts of our games just because they're really good at something, we happen to know them, and we happen to be talking to them one day, and so they just kind of jump on."

There are also so many references littered throughout Romeo is a Deadman, from artwork parodying The Clash's London Calling album cover at the end of each chapter to Oscar Wilde quotations that, on one hand, would be a fever dream for pop culture junkies but, on the other, could feel like it lacks any cohesion. Suda, however, freely admits that he doesn't try to look too deeply into the art or culture he borrows from, having tried and struggled with reading the Japanese translation of Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet before settling on the Baz Lurhnam film adaptation.

A culture clash

"When I reference a specific piece of culture, like a person, a story, a movie, a book, instead of looking really deeply into it and making sure it's as close to the original as possible, I usually just base it off the idea that I have," he explains. "I don't try too hard to make things too close to the things that I'm referencing, because I feel like a lot of people who know more about these things than I do would notice that and be like, this guy's trying too hard. I make sure that I have at least a general knowledge of the stuff I'm referencing, and then I think about the way that I want to visualise it in the game."

Funnily enough, that's a similar approach when referencing Grasshopper's own games. Romeo is a Deadman may be the first original IP for the studio in a decade, but fans can still pick up nods to the studio's other titles, be it the way Romeo finishes off one boss with a move that would be more attributed to No More Heroes protagonist Travis Touchdown than to other characters. Suda had even planned to incorporate Shadows of the Damned's antagonist, Fleming, into the game, but that didn't happen due to scheduling and budgetary constraints. Other times, they're a lot less planned.

"When I started writing the scenario and thought of the FBI spacetime police, I remembered back in The Silver Case and 25th Ward games, there were these two cops who were able to travel through space-time, so I was like, I could bring these guys back and put them in the game," he says. "But I don't necessarily sit down and decide I have to figure out ways to jam in characters from my old games. And sometimes they're the same character, sometimes they're just the same in name only."

In other words, if you're looking to find this clean, clear Grasshopperverse that conforms to lore, you'll probably be disappointed. But again, it just further shows the chaotic ad-lib nature of the studio, which is why, after nearly 28 years, despite these days being a subsidiary of Chinese conglomerate NetEase, it's still proudly and unapologetically a company where punk's not dead.

Romeo is a Deadman releases for PS5, Xbox Series X/S and PC on 11 February.

Alan Wen is a freelance journalist writing about video games in the form of features, interview, previews, reviews and op-eds. Work has appeared in print including Edge, Official Playstation Magazine, GamesMaster, Games TM, Wireframe, Stuff, and online including Kotaku UK, TechRadar, FANDOM, Rock Paper Shotgun, Digital Spy, The Guardian, and The Telegraph.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.