Why you shouldn't fear the LHF ad ban

The Less Healthy Food ban presents an opportunity for creatives.

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

The UK’s new LHF (Less Healthy Food) regulations probably feel less like policy and more like a creative straightjacket. The new rules mean product shots curtailed and creator-led endorsements restricted. One of the most familiar, frictionless tools in modern advertising is suddenly off the table.

But here’s the provocation for creatives: what if this policy is actually a liberator? What if it will help us create the next set of best adverts?

It forces us to confront something uncomfortable yet undeniable: product-first advertising has become a creative crutch. And when you take that crutch away, you’re forced to learn how to walk again.

Regulation breeds creativity

At first glance, the LHF regulations look like they penalise digital, social and creator-led work disproportionately. While LHF ads on TV and OOH are only restricted pre-watershed, paid promotions on creators’ own channels are now banned – with brand-owned channels retaining more flexibility.

That imbalance is frustrating. But creatively, it’s not fatal. Hopefully, by now, most brands have already moved on from transactional sales-led marketing.

Audiences have rejected that model for a while now. System1 / TikTok research consistently shows that assets built for ‘showmanship’ – advertising built primarily for entertainment – outperforms assets built for ‘salesmanship’. Advertisers adopting this approach can expect to deliver a 39 per cent increase in memorability.

And so, seen in this light, the reality of the LHF ad ban is that it doesn’t end creative opportunity; it ends creative shortcuts.

Sign up to Creative Bloq's daily newsletter, which brings you the latest news and inspiration from the worlds of art, design and technology.

Lessons from the past

If you think back to some of the most memorable adverts of this century, you might think of: Guinness’s Surfer ad; Cadbury’s drumming Gorilla or their dancing eyebrows; John Lewis’ Christmas adverts. And, more recently McDonald’s Raise the Arches ad campaign.

What do they all have in common? There was barely a product in sight. Instead, they created distinctive and immersive worlds to evoke a feeling you might associate with the brand. Whether it’s escapism, fun, kindness.

When regulation forces brands to be less literal, that’s often when you see the most interesting creative work emerge.

When the product disappears, brand craft takes centre stage

When Garnier faced strict Nordic regulations banning filters in creator content, we worked with the brand to pivot away from conventional creator formats and into immersive AR experiences that let users explore skin and hair outcomes interactively, without relying on visual manipulation. The constraint didn’t weaken the idea – it elevated the campaign.

The same pattern is repeating now with the LHF ad ban. When the product disappears, brand craft takes centre stage.

For creatives, the most profound shift LHF introduces is this: if you can’t rely on the product shot, everything else has to work harder. But the outcome will also be better.

Solving the LHF conundrum

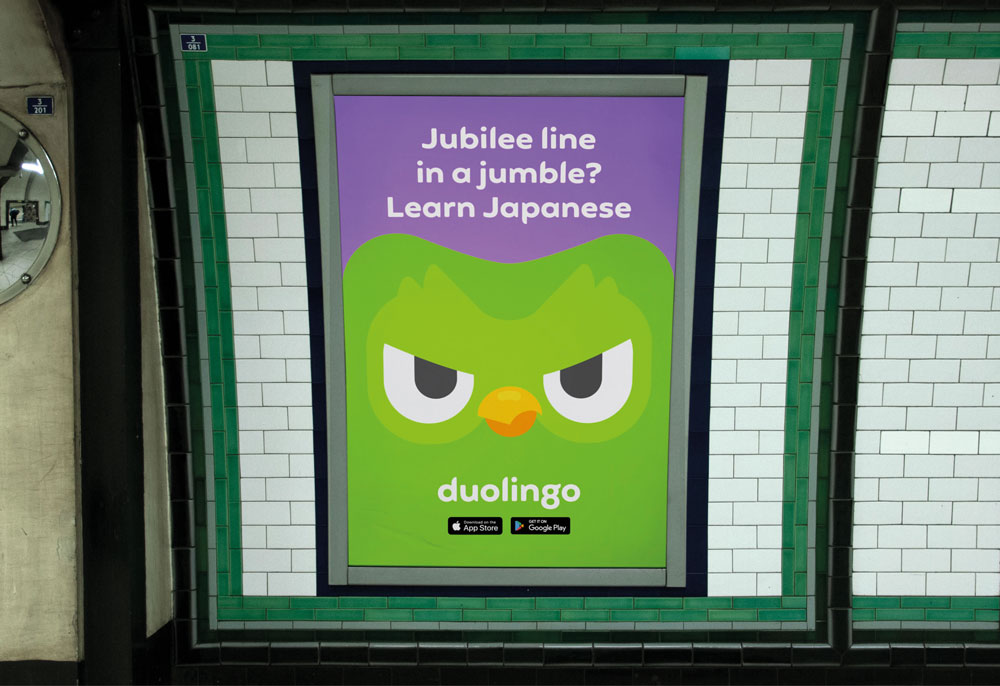

Distinctive brand assets become non-negotiable. Colour, typography, sound, characters, rhythm, tone of voice. Think: DuoLingo’s iconic mascot, Duo; Ryanair’s inimitable abrasive tone of voice; McDonald’s I’m Loving It jingle. The System 1 / TikTok research shows that early and well branded creator assets drive twice the awareness lift and 3x brand image lift.

For creatives, this means thinking less in executions and more in systems. Less 'what does this ad look like?' and more 'what does this brand sound, feel and behave like wherever it shows up?'

And that presents both a problem and an opportunity.

Legacy brands who have built distinctive assets over decades have a head start. If your colour, jingle or characters are already embedded in culture, removing the product image hurts less.

Challenger brands have agility on their side

On the flipside, challenger brands have agility on their side. They can build distinctive codes faster precisely because they’re unburdened by history. In the social era, consistency compounds quickly. One bold colour, one sonic cue, one point of view – repeated relentlessly – can build recognition in years rather than decades.

It’s also worth noting that SMEs are exempt from LHF regulations, giving smaller brands a window to balance product-led activity with longer-term brand-building. Smart agencies will use that time to help challengers invest in the codes they’ll need when regulation eventually catches up with them.

Creators don’t disappear – they evolve

One of the biggest misconceptions about LHF is that it sidelines creators. But in reality, it simply changes the role they play.

Creators become less like product demonstrators and more like collaborators, performers and storytellers. That demands better briefs and braver thinking.

Instead of asking creators to hold a product and hit three USPs, we now need to invite them into a brand world – with clear boundaries, consistent codes and creative freedom inside those constraints. The work becomes more like entertainment commissioning than influencer activation.

Measurement needs to catch up with creativity

One of the biggest risks for agencies is trying to judge LHF-era work using pre-LHF metrics.

If you optimise brand-world ideas against short-term conversion benchmarks designed for product ads, you will inevitably conclude that “it doesn’t work”. That’s not a creative failure – it’s a measurement mismatch.

We already know from Billion Dollar Boy research that a measurement disconnect exists in creator marketing which is undermining performance. Brands are typically briefing creators to grow brand awareness (41%) and reach new audiences (37%) – the most common creator marketing objectives – but they’re measuring success against return on investment (60%) and customer acquisition (60%).

The reality is that creator marketing is a full-funnel channel – and the IPA has the receipts. Recent research spanning 220 campaigns from 144 brands across 36 sectors and 28 markets shows that influencer marketing delivers strong returns, both over the short term and especially over the long term – where it outperforms every other channel.

Viewed through this prism, marketers need to reconsider how they measure performance – not just looking at sales or vanity metrics. But, in the age of LHF, looking at brand lift, attention, memory structures, search intent and cultural relevance. These will become far more important signals for brands to benchmark success.

The creative opportunity hiding in plain sight

LHF accelerates a shift from product-first marketing to brand-world building. It rewards imagination over repetition. It values emotion, humour and humanity over functional persuasion.

For creatives, that’s not a threat – it’s an invitation.

An invitation to design brands as living systems, not just campaigns. To collaborate with creators as cultural partners, not media placements. To put craft, consistency and creativity back at the centre of commercial effectiveness.

If the last decade trained us to optimise, the next will challenge us to imagine again.

Thom co-founded BDB Group in 2014 with a mission to help turn the creator economy into a trusted, enterprise-ready marketing channel, and over the past 11 years has led the Group’s growth into a global creator-first social business operating across 65 markets.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.