15 influential art and design movements you should know

Brush on up your knowledge of these major periods in art and design history.

01. Impressionism

02. Arts and Crafts

03. Art Nouveau

04. Cubism

05. Futurism

06. Constructivism

07. Bauhaus

08. Art Deco

09. Surrealism

10. Abstract Expressionism

11. Swiss Design/ ITS

12. Pop Art

13. Minimalism

14. Postmodernism

15. Memphis

As a designer, inspiration can come from anywhere. But sometimes influences, attitudes and approaches converge to form a coherent movement that has a knock-on effect around the world.

There have been hundreds of art and design movements of different sizes and significance over the centuries – some centred on the style or approach of a particular collective of artists in a particular place, others spanning many creative disciplines, and much more organic in terms of interpretation.

Whether they happened 150 years ago or 30 years ago, the impact of many of these is still felt today – you may even have felt their influence without knowing it. These things often move in cycles, particularly with the contemporary trend for retro aesthetics. So a little knowledge of art history goes a long way.

There are certain art and design movements that creatives need to be familiar with. Read on for our comprehensive guide to 15 of the most influential art and design movements of the 20th century.

We've put these in chronological order, with the examples on page 2 and page 3 most relevant to graphic designers, and those on this page and page 2 likely to inspire more artists and illustrators. Use the quick links menu to jump straight to the section you'd like to explore first, or scroll on to read them in order.

Click on the icon at the top-right of the image to enlarge it.

01. Impressionism and Post-Impressionism

Developing primarily in France during the late 19th century, Impressionism was a fine art movement in which a small group of painters eschewed the then-traditional emphasis on historical or mythological subject matter in favour of depicting visual reality, and particularly the transient nature of light, colour and texture.

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

Seven painters were at the core of this hugely influential movement: Claude Monet, Pierre Auguste Renoir, Camille Pissarro, Alfred Sisley, Berthe Morisot, Armand Guillaumin and Frédéric Bazille – and worked and exhibited together.

The Impressionists abandoned the established palette of muted greens, browns and greys for their landscapes in favour of a much brighter, expressive range of colours in an attempt to depict conditions such as dappled sunlight, and reflections on rippled water.

Instead of greys and blacks for shadows, they used a whole range of complementary colours – and objects were depicted using dabs of paint rather than defined with a hard outline.

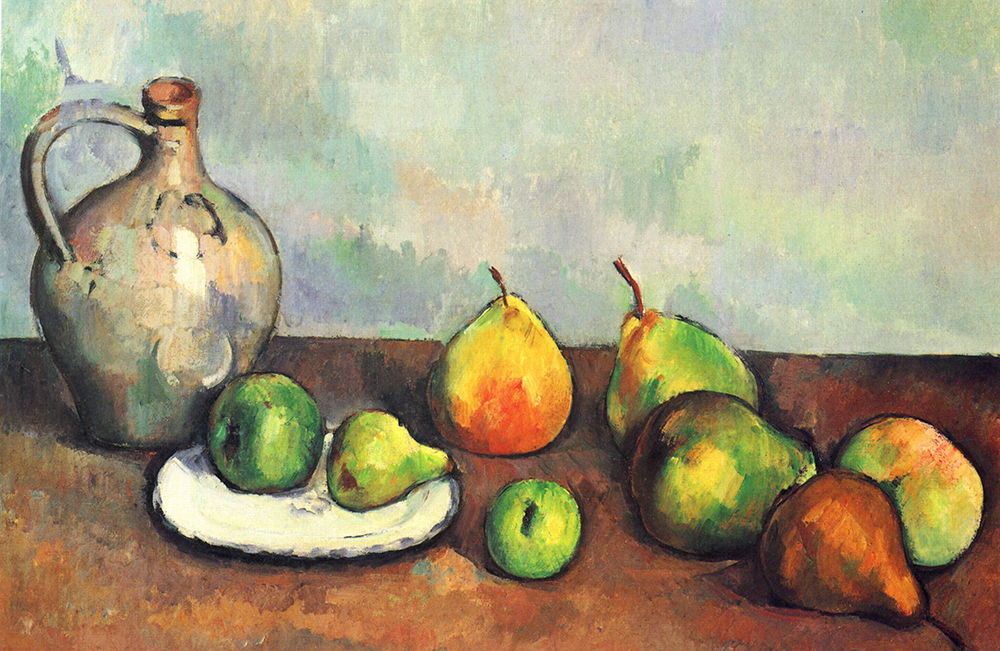

Post-Impressionism embraced many of the tenets of its predecessor movement, whilst also rejecting some of its limitations. Painters such as Paul Cézanne, Georges Seurat, Paul Gauguin, Vincent van Gogh and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec used similarly pure, brilliant colour palettes and expressive, short brush strokes, but also sought to elevate the work to something less transient and experimental.

Rather than ever-changing conditions of natural light and its effect on colour, Cezanne and the other Post-Impressionists focussed more on solid, permanent objects, with still-life paintings – such as Cezanne's Pitcher and Fruit, and van Gogh's Sunflowers – emblematic of the movement.

02. Arts and Crafts

As a reaction to the rise of mass production (and corresponding decline of artisan craftsmanship) during the Industrial Revolution, there was a resurgence of interest in decorative arts across Europe in the second half of the 19th century – fittingly known as the Arts and Crafts movement.

At the vanguard of this new movement was reformer, poet and designer William Morris, who formed a collective of collaborators in the 1860s to try to reawaken the handcrafted quality of the medieval period. They produced beautiful metalwork, jewellery, wallpaper, textiles and books.

By 1875, this collective became known as Morris and Company, and by the 1880s the attitude and techniques they practiced had inspired a whole new generation of designers, and the Arts and Crafts movement was born.

While many criticised the practicality of such intricate handicrafts in the modern, industrialised world, the influence of the movement endures to this day.

03. Art Nouveau

Following on from the Arts and Crafts movement, Art Nouveau was a primarily ornamental movement in both Europe and the USA. One distinctive characteristic of the style is the use of organic, asymmetrical line work instead of solid, uniform shapes – applied across architecture, interiors and jewellery, as well as posters and illustration.

Intricate ironwork, stained glass, ceramics and ornamental brickwork were used expressively, with freeform lines taking precedence over any pictorial elements in the designs, which were often inspired by delicate forms found in nature, such as flower stems, vines, creepers, tendrils and insect wings.

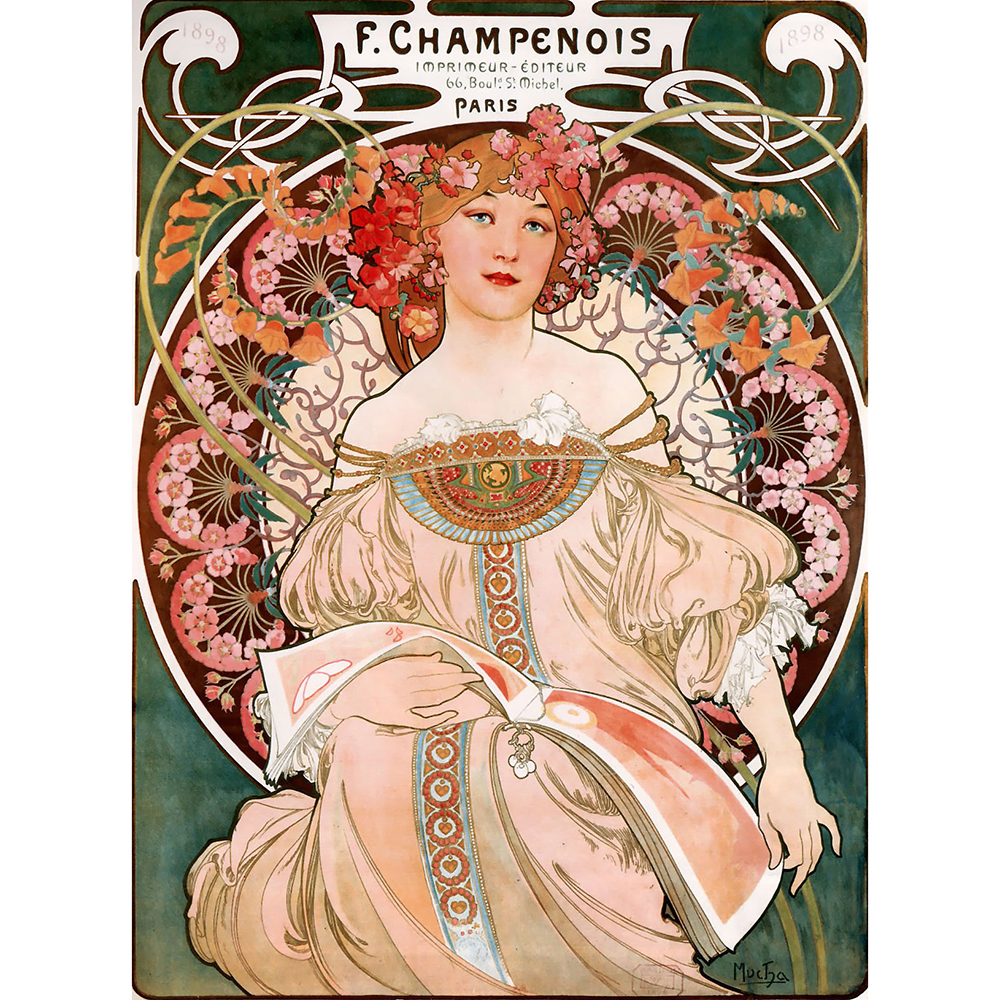

Scottish architect and designer Charles Rennie Mackintosh was a leading exponent of the Art Nouveau movement, as well as Czech graphic artist Alphonse Mucha, and iconic Spanish architect and sculptor Antonio Gaudí – whose magnum opus, Barcelona's La Sagrada Família, has famously been under construction for more than 130 years.

Mucha's stunning artworks, many of which were commercial commissions for advertising clients, combined the flowing organic lines and natural motifs of the Art Nouveau style with sensual portraits of women.

While the decorative style fell out of fashion after 1910, it saw a resurgence in the 1960s thanks to a series of major exhibitions in London, Paris and New York, which retrospectively helped elevate a style once seen as a passing fad to the status of an international movement that influenced fashion, music design and advertising.

04. Cubism

Two artists were instrumental in founding the Cubist movement: Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. Unlike the expressive attempts to capture natural conditions in Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, Cubism was about flat, two-dimensional, distorted objects – sacrificing accurate perspective in favour of surreal fragmentation.

The name came from a disparaging remark by art critic Louis Vauxcelles, who described Braque’s 1908 work Houses at L’Estaque as being "composed of cubes". But it was Picasso's Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, painted the previous year, that set the wheels in motion, depicting five female nudes as fractured, angular shapes.

As Braque and Picasso continued to explore how abstract shapes could be used to define familiar objects, the period from 1910-1912 is often referred to as Analytical Cubism. A distinctive palette of tan, brown, grey, cream, green and blue prevailed, and common subjects included musical instruments, bottles, newspapers, and the human body.

Post-1912 this evolved into Synthetic Cubism, where multiple forms are combined within the increasingly colourful artworks, which made use of collage techniques to explore texture. The visual language defined by Braque and Picasso was later embraced by many other painters, and also influenced sculptors and architects such as Le Corbusier.

05. Futurism

Founded in Italy in the early 20th century, Futurism attempted to capture the pace, vitality and restlessness of modern life through highly expressive artwork that ultimately glorified war, Fascism and the machine age. The aesthetic style would later spread across Europe, and notably into Russia.

The movement was officially announced in 1909 when Parisian newspaper Le Figaro published a manifesto by Italian poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, who coined the term to describe how his work celebrated social progress and cultural innovation.

Cutting-edge technology such as the automobile was put on a pedestal, while traditional values – and historical institutions such as museums and libraries – were aggressively repudiated.

Two of the leading proponents of Futurism, Umberto Boccioni and Antonio Sant'Elia, were killed in combat in 1916. However, the aesthetic would go on to be expressed in modern architecture, as visions of mechanised cities defined by towering skyscrapers became a reality, while artists such as Tullio Crali kept the style going into the 1930s.

Next page: Mid-20th century art and design movements

Current page: Early 20th century artistic movements

Next Page Mid 20th century art and design movements

Nick has worked with world-class agencies including Wolff Olins, Taxi Studio and Vault49 on brand storytelling, tone of voice and verbal strategy for global brands such as Virgin, TikTok, and Bite Back 2030. Nick launched the Brand Impact Awards in 2013 while editor of Computer Arts, and remains chair of judges. He's written for Creative Bloq on design and branding matters since the site's launch.